The following interview with Ümit Kurt tackles how the physical

annihilation of the Armenians paralleled the confiscation and

appropriation of their properties in 1915. By citing the various laws

and decrees that orchestrated the confiscation process, Kurt places our

understanding of the genocide within a legal context.

Ümit Kurt is a native of Aintab, Turkey, and holds a bachelor of

science degree in political science and public administration from

Middle East Technical University, and a master’s degree from Sabancı

University’s department of European studies. He is currently a Ph.D.

candidate in the department of history at Clark University and an

instructor at Sabancı University. He is the author of several books,

including Kanunların Ruhu: Emval-i Metruke Kanunlarında Soykırımın İzlerini Aramak (The Spirit of Laws: Seeking the Traces of Armenian Genocide in the Laws of Abandoned Property,

2012) with Taner Akçam. His main area of interest is the confiscation

of Armenian properties and the role of local elites/notables in Aintab

during the genocide. Below is the full text of the interview Kurt

granted The Armenian Weekly earlier this month.

***

Varak Ketsemanian: What were the laws and regulations that governed the confiscation of Armenian properties during the genocide?

Ümit Kurt: A series of laws and decrees, known as the Abandoned Properties Laws (Emval-i Metruke Kanunları),

were issued in the Ottoman and Turkish Republican periods concerning

the administration of the belongings left behind by the Ottoman

Armenians who were deported in 1915. The best-known regulation on the

topic is the comprehensive Council of Ministers Decree, dated May 30, 1915. The Directorate of Tribal and Immigrant Settlement of the Interior Ministry (İskan-ı Aşâir ve Muhacirin Müdiriyeti) sent

it the following day to relevant provinces organized in 15 articles. It

provided the basic principles in accordance with which all deportations

and resettlements would be conducted, and began with listing the

reasons for the Armenian deportations. The most important provision

concerning Armenian properties was the principle that their equivalent

value was going to be provided to the deportees.

The importance of the decree of May 30 and the regulation of May 31

lie in the following: The publication of a series of laws and decrees

were necessary in order to implement the general principles that were

announced in connection with the settlement of the Armenians and the

provision of the equivalent values of their goods. This never happened.

Instead, laws and decrees began to deal with only one topic: the

confiscation of the properties left behind by the Armenians.

Another regulation was carried out on June 10, 1915. This

34-article ordinance regulated in a detailed manner how the property and

goods the Armenians left behind would be impounded by the state. The

June 10, 1915 regulation was the basis for the creation of a legal

system suitable for the elimination of the material living conditions of

the Armenians, as it took away from the Armenians any right of disposal

of their own properties. Article 1 of the June 10, 1915 regulation

announced that “committees formed in a special manner” were going to be

created for the administration of the “immovable property, possessions,

and lands being left belonging to Armenians who are being transported to

other places, and other matters.”

The most important of these committees were the Abandoned Properties Commissions (Emval-i Metruke Komisyonları).

These commissions and their powers were regulated by Articles 23 and

24. The commissions were each going to be comprised of three people, a

specially appointed chairman, an administrator, and a treasury official,

and would work directly under to the Ministry of the Interior.

The most important steps toward the appropriation of Armenian cultural and economic wealth were the Sept. 26, 1915 law of 11 articles, and the 25-article regulation of Nov. 8, 1915 on how the aforementioned law would be implemented.

Many matters were covered in a detailed fashion in the law and the

regulation, including the creation of two different types of commissions

with different tasks called the Committees and Liquidation Commissions (Heyetler ve Tasfiye Komisyonları);

the manner in which these commissions were to be formed; the conditions

of work, including wages; the distribution of positions and powers

among these commissions and various departments of ministries and the

state; the documents necessary for applications by creditors to whom

Armenians owed money; aspects of the relevant courts; the rules to be

followed during the process of liquidation of properties; the different

ledgers to be kept, and how they were to be kept; and examples of

relevant ledgers. This characteristic of the aforementioned law and

regulation is the most important indication of the desire not to return to the Armenians their properties or their equivalent value.

The Temporary Law of Sept. 26, 1915 is also known as the Liquidation Law (Tasfiye Kanunu).

Its chief goal was the liquidation of Armenian properties. According to

its first article, commissions were to be established to conduct the

liquidation. These commissions were to prepare separate reports for each

person about the properties, receivable accounts, and debts “abandoned

by actual and juridical persons who are being transported to other

places.” The liquidation would be conducted by courts on the basis of

these reports.

The temporary law also declared that a regulation would be

promulgated about the formation of the commissions and how the

provisions of the law would be applied. This regulation, which was

agreed upon on Nov. 8, 1915, regulated in a detailed fashion the

protection of the movable and immovable property of Armenians who were

being deported, the creation of new committees for liquidation issues,

and the working principles of the commissions. The two-part regulation

with 25 articles moreover included explanatory information on what had

to be included in the record books to be kept during the liquidation

process, and how these record books were to be used.

In brief, these were the major legal rules and regulations in 1915.

VK: How did the Ottoman government deal with the property of

Armenians living in Istanbul, since no actual massacres took place in

the capital? Were there laws for them, too?

UK: It is very important to note that these laws and statutes

were known as the Abandoned Properties Laws, which was the official

euphemism and an established term in the CUP propaganda to characterize

the expropriation of the Armenians, and were merely applied to deported Armenians.

Movable and immovable properties of Armenians who were not deported

were not subjected to the Abandoned Properties Laws. As known, there

were some Armenians deported from Istanbul—of course, very limited

compared to Western Armenia—and properties of those deported Armenians

in Istanbul also went through this process of confiscation,

expropriation, and liquidation of their properties.

VK: How does the concept of confiscation and destruction of property help us understand the broader picture of the genocide?

UK: Actually, a new group of critical genocide scholars has

started to come up with a new definition of genocide by taking into

consideration the confiscation and destruction of property and wealth of

the victim groups. In doing so, these critical genocide scholars have

brought Raphael Lemkin’s original definition of genocide to the

attention of existing genocide scholarship.

I see Raphael Lemkin as the founding father of genocide literature.

Lemkin introduced the concept of genocide for the first time in 1944 in

his book entitled Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. The book consists

of a compilation of 334 laws, decrees, and regulations connected with

the administration of 17 different regions and states under Nazi

occupation between March 13, 1938 and Nov. 13, 1942. That is to say,

Lemkin did not introduce the concept of genocide together with the

barbaric practices like torture, oppression, burning, destruction, and

mass killing observed in all genocides, but through a book quoting and

analyzing legal texts. Could this be a coincidence?

Given its importance, it is necessary to stress this one more time:

In the year that Lemkin completed the writing of his book (1943), he

already knew of all the crimes perpetrated by Nazi Germany. However, he

did not present the concept of genocide in a framework elucidated by

these crimes. On the contrary, he introduced it through some laws and

decrees that were published on how to administer occupied territories

and that perhaps in the logic of war might be considered “normal.” We

cannot say that this situation accords well with our present way of

understanding genocide. In the general perception, genocide is the

collapse of a normally functioning legal system; it is the product of

the deviation of the system from the “normal” path. According to this

point of view, genocide means that the institutions of “civilization”

are not working and are replaced by barbarism. Lemkin, however, seems to

be saying the complete opposite of this, that genocide is hidden in

ordinary legal texts. By doing this, it is as if he is telling us not to

look for the traces of genocide as barbaric manifestations that can be

defined as inhuman, but to follow their trail in legal texts.

Genocide as a phenomenon fits inside the legal system—this is an

interesting definition. And this definition is one of the central theses

of our book. The Armenian Genocide does not just exist in the displays

of barbarity carried out against the Armenians. It is at the same time

hidden in a series of ordinary legal texts.

What we wish to say in our book is that genocide does not only mean

physical annihilation. Going even further, we can assert that we are

faced with a phenomenon in which whether the Armenians were physically

annihilated or not, is but a detail. How many Armenians died during the

course of the deportations/destruction or how many remained alive is

just a secondary issue from a definitional point of view; what is

important is the complete erasure of the traces of the Armenians from

their ancient homeland.

The total destruction of the Armenians marked the fact that a

government tried to eliminate a particular group of its own citizens in

an effort to settle a perceived political problem. Between 1895 and

1922, Ottoman Armenians suffered massive loss of life and property as a

result of pogroms, massacres, and other forms of mass violence. The 1915

Armenian Genocide can be seen as the pinnacle of this process of

decline and destruction. It consisted of a series of genocidal

strategies: the mass executions of elites, categorical deportations,

forced assimilation, destruction of material culture, and collective

dispossession. The state-orchestrated plunder of Armenian property

immediately impoverished its victims; this was simultaneously a

condition for and a consequence of the genocide. The seizure of the

Armenian property was not just a byproduct of the CUP’s genocidal

policies, but an integral part of the murder process, reinforcing and

accelerating the intended destruction. The expropriation and plunder of

deported Armenians’ movable and immovable properties was an essential

component of the destruction process of Armenians.

As Martin Dean argues in Robbing the Jews: The Confiscation of Jewish Property in the Holocaust, 1933-1945,

ethnic cleansing and genocide usually have a “powerful materialist

component: seizure of property, looting of the victims, and their

economic displacement are intertwined with other motives for racial and

interethnic violence and intensify their devastating effects.” In the

same vein, the radicalization of CUP policies against the Armenian

population from 1914 onward was closely linked to a full-scale assault

on their property.

Thus, the institutionalization of the elimination of the

Christian-Armenian presence was basically realized, along with many

other things, through the Abandoned Properties Laws. These laws are

structural components of the Armenian Genocide and one of the elements

connected to the basis of the legal system of the Republican period. It

is for this reason that we say that the Republic adopted this genocide

as its structural foundation. This reminds us that we must take a fresh

look at the relationship between the Republic as a legal system and the

Armenian Genocide.

The Abandoned Properties Laws are perceived as “normal and ordinary”

laws in Turkey. Their existence has never been questioned in this

connection. Their consideration as natural is also an answer as to why

the Armenian Genocide was ignored throughout the history of the

Republic. This “normality” is equivalent to the consideration of a

question as non-existent. Turkey is founded on the transformation of a

presence—Christian in general, Armenian in particular—into an absence.

This picture also shows us a significant aspect of genocide as Lemkin

pointed out. Genocide is not only a process of destruction but also

that of construction. By the time genocide perpetrators are destroying

one group, they are also constructing another group or identity.

Confiscation is an indispensable and one of the most effective

mechanisms for perpetrators to realize the aforementioned process of

destruction and construction.

VK: What happened to the property after it was seized from the Armenians?

UK: Most of the Armenians properties were distributed to

Muslim refugees from the Balkans and Caucasia at that time. Central and

local politicians and bureaucrats of the Union and Progress Party also

made use of Armenian properties.

The exhaustive process of administering and selling the property

usually involved considerable administrative efforts, employing hundreds

of local staff. Economic discrimination and plunder contributed

directly to the CUP’s process of destruction in a variety of ways. At

the direct level of implementation, the prospect of booty helped to

motivate the local collaborators in various massacres and the

deportation orchestrated by the CUP security forces in Anatolia in

general.

The CUP cadres were quite aware that the retention of the Armenian

property would give the local people a material stake in the deportation

of the Armenians. In many cities of Anatolia, especially local notables

and provincial elites who had close connections with the CUP obtained

and owned most of the properties and wealth of Armenians. This process

was realized in Aintab, Diyarbekir, Adana, Maras, Kilis, and other

cities in the whole Anatolia. For my Ph.D. dissertation project, I am

exploring how Armenians properties and wealth changed hands and were

taken over by local elites of the city during the genocide.

Similar to the policy of Nazi leaders regarding the “Aryan”ization of

Jewish property in the Holocaust, the CUP aimed to have complete

control over the confiscation and expropriation of Armenian properties

for the economic interests of the state, but could not prevent incidents

of corruption from taking place.

It should be emphasized that corruption was fairly rift among

bureaucrats and officers of the Abandoned Properties Commissions and

Liquidation Commissions who were the responsible actors for

administering and confiscating Armenian properties under the supervision

and for the advantage of the state, as did happen in the “Aryan”ization

of Jewish property.

Despite the widespread incidence of private plunder and corruption,

there is no doubt that the seizure of Armenian property in the Ottoman

Empire was primarily a state-directed process linked closely to the

development of the Armenian Genocide. However, the widespread

participation of the local population as beneficiaries of the Armenian

property served to spread complicity, and also legitimize the CUP’s

measures against the Armenians.

A number of leading members of the Central Committee of the Union and Progress Party, as well as CUP-oriented governors and mutasarrıfs, seized a great deal of property, especially those belonging to affluent Armenians in many vilayets.

In addition, according to one argument, CUP leaders also utilized

Armenian property and wealth to meet the deportation expenses.

Also, it is worth mentioning an important detail on the National Tax Obligations (Tekâlif-i Milliye)

orders. This topic is important to show the Nationalist movement’s

viewpoint concerning the Armenians, and also Greeks and the properties

they left behind. The National Tax Obligations Orders were issued by

command of Mustafa Kemal, the head of the Grand National Assembly and

commander-in-chief of the Turkish Nationalist army, to finance the War

of Independence against Greece. The abandoned properties of Armenians

were also seen as an important source of financing for the war between

1919 and 1922.

After the establishment of the Turkish Republic, in 1926, Turkish

Grand National Assembly passed a law. This law was promulgated and

enforced on June 27, 1926. According to this law, Turkish governmental

officers, politicians, and bureaucrats who were executed as a result of

their roles in the Armenian deportations or who were murdered by

Dashnaks were declared “national heroes,” and so-called Abandoned

Properties of Armenians were given to their families.

And finally in 1928, the Turkish Republic introduced a new regulation that granted muhacirs

or Muslim refugees who were using Armenian properties the right to have

the title deeds of those properties, which included houses, lands,

field crops, and shops.

As you can see, a variety of actors and institutions seized

properties and wealth that the deported Armenians were forced to leave

behind.

VK: What did this entire process of confiscation and

appropriation represent, on the one hand to the Ottoman Elite, and on

the other to the average Turk? Was it an ideological principle or a mere

motivating element for further destruction?

UK: We should be very cautious when giving a proper answer to

this question. Also, in my view, this aspect of the Armenian Genocide

should be compared with the “Aryan”ization of Jewish properties in the

Holocaust. We can see palpable resemblances between these two

dispossession processes.

It is obvious that the material stake for the average Turkey played a

significant role in his/her participation in the destruction process of

Armenians. Economic motivation was always present and enabled CUP

central actors to carry out their ultra-nationalist ideological policies

against Armenians in terms of gaining the support and consent of

average Turkish-Muslim people.

To have a better appreciation of the motivation of the average Turk,

one should look at what happened at the local level—which means we need

more local and micro studies in order to understand how the deportation

and genocide alongside the plunder and pillage of Armenian properties

took place in various localities in Anatolia.

The process of genocide and deportation directed at the Armenians

was, in fact, put into practice by local notables and provincial elites.

These local actors prospered through the acquisition of Armenians’

property and wealth, transforming them into the new wealthy social

stratum. In this respect, the Union and Progress Party’s genocide and

deportation decree on May 27, 1915 had a certain social basis through

the practice of effective power, control, and support mechanism(s) at

local levels. Therefore, a more accentuated focus on the local picture

or the periphery deserves closer examination.

The function of the stolen Armenian assets in the Turkification

process makes the confiscation of Armenian properties a social matter.

In this respect, the wide variety of participants and the dynamic

self-radicalization of the CUP and state institutions at the local level

need to be examined. Although the CUP was involved throughout the

confiscation process and was fully in charge of it, the collaboration of

local institutions and officers also played a considerable role. The

local institutions and offices could not operate in complete isolation

from their respective societies and the prevailing attitudes in them.

The expropriation of the Armenians, therefore, was not limited simply

to the implementation of the CUP orders, but was also linked to the

attitude of local societies towards the Armenians, that is, to the

different forms of Armenian hatred. As in the empire, the corruptive

influence that spread with the enrichment from Armenian properties in

Anatolia could also have led to various forms of accommodation of CUP

policies. The robbery of the property is also a useful barometer to

assess the relations of various local populations toward the CUP, to the

CUP central and local authorities, and also toward the Armenian

population in each city.

With regard to the widespread collaboration of parts of the local

populace in measures taken against the Armenians, the distribution of a

great amount of the Armenian property provided a useful incentive that

reinforced hatred for the local Armenians as well as other political and

personal motives.

One should keep in mind the fact that the participation of local

people is a necessary condition to ensure the effectiveness of genocidal

policies. Planned extermination of all members of a given category of

people is impossible without the involvement of their neighbors—the only

ones who know who is who in a local community.

Therefore, the entire process of confiscation can be evaluated and

construed as both an ideological principle and economic motivation.

These two aspects cannot be separated from each other in our analysis.

In my view, the ideological principle was hugely supported and

complemented by economic motivation and material stakes. In some

instances, ideology played a more significant role than economic

motivation, and in other instances economic interests came into

prominence vis-à-vis ideology. Yet, in any case, these two parameters

were on the ground and constituted effective mechanisms and dynamic in

the confiscation, plunder, and seizure of Armenian material wealth.

Sunday, September 29, 2013

Woman in Turkey Reveals Armenian Identity After 82 Years

Woman in Turkey Reveals Armenian Identity After 82 Years

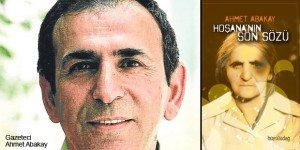

Hoşana, who was brought up as an Alevi in a Kurdish village, told the secret to her youngest son, journalist Ahmet Abakay.

Abakay, who is the president of a journalists’ association, has now published a book, titled Hoşana’nın Son Sözü (Hoşana’s Last Word), detailing his mother’s story.

“How can a person hide her Armenian roots for 82 years from her family, children, grandchildren, and her environment?” asks Abakay, according to an article on the Turkish website T24.com.tr.

In recent years, countless stories of Turkish and Kurdish persons revealing their Armenian identity have appeared in the media.

Friday, September 13, 2013

Mouradian: Encounter with a Skull

We stand aghast at the entrance of an Armenian monastery* perched on a hill near Lake Van.

“Is that what I think it is?” I ask George, my companion on a trip to document Armenian cultural heritage in Turkey.

“Can’t be,” he replies in disbelief. “Must be a soccer ball.”

I go past broken khatchkars (Armenian cross-stones) and around large holes dug up by treasure hunters—a familiar site for visitors of historic Armenian churches in Turkey—and shudder.

The orbital cavities of a skull are staring at me.

Nothing could have prepared me for that eye contact with an ancestor

who had resurfaced a century after the genocide of my people. Not all

the bones and skulls I’ve seen at memorials, not the hundreds of horror

stories I’ve heard locals tell of what their forefathers did to

Armenians.

I approach and hold the skull in my hands with an affection bordering on the macabre.

Who was this person whose remains were dug out and tossed aside? A clergyman? Perhaps the abbot of the monastery? After all, it was customary to bury clergy inside the narthex.

I can’t help but think that after the murder of a nation, the theft of a people’s land and wealth, and the ongoing denial of the crime, the skeletons are coming out—literally—with a little help from Turks and Kurds who want yet more Armenian gold, more booty, and don’t mind more desecration and destruction.

I don’t want to leave the skull behind, but after a brief discussion with George, we agree to inter it not far away from the hill.

I place the tortured cranium in my hat and we leave the monastery in search for an inconspicuous—and, hopefully, final—resting place.

Soon I, too, am digging a hole.

We bury the skull, while the breeze over Lake Van whispers a prayer.

At some point on the way back, I realize I am wearing my ash-covered hat. I had unwittingly put it back on after burying the skull.

That evening, the mirror in my hotel room shows a dusting of white ash on my hair.

*The name and exact location of the monastery are withheld out of concerns of further desecration.

Author’s [naïve] question: After decades of actively destroying Armenian cultural and religious sites in Turkey and allowing vandals and treasure hunters to finish the job by digging, drilling, and defacing, is it not time for Turkish authorities to break with past practices and initiate a program aimed at stabilizing structures and preventing further vandalism?

“Is that what I think it is?” I ask George, my companion on a trip to document Armenian cultural heritage in Turkey.

“Can’t be,” he replies in disbelief. “Must be a soccer ball.”

I go past broken khatchkars (Armenian cross-stones) and around large holes dug up by treasure hunters—a familiar site for visitors of historic Armenian churches in Turkey—and shudder.

The orbital cavities of a skull are staring at me.

Nothing could have prepared me for that

eye contact with an ancestor who had resurfaced a century after the

genocide of my people. (Photo by George Aghjayan)

I approach and hold the skull in my hands with an affection bordering on the macabre.

Who was this person whose remains were dug out and tossed aside? A clergyman? Perhaps the abbot of the monastery? After all, it was customary to bury clergy inside the narthex.

I can’t help but think that after the murder of a nation, the theft of a people’s land and wealth, and the ongoing denial of the crime, the skeletons are coming out—literally—with a little help from Turks and Kurds who want yet more Armenian gold, more booty, and don’t mind more desecration and destruction.

I don’t want to leave the skull behind, but after a brief discussion with George, we agree to inter it not far away from the hill.

I place the tortured cranium in my hat and we leave the monastery in search for an inconspicuous—and, hopefully, final—resting place.

Soon I, too, am digging a hole.

We bury the skull, while the breeze over Lake Van whispers a prayer.

At some point on the way back, I realize I am wearing my ash-covered hat. I had unwittingly put it back on after burying the skull.

That evening, the mirror in my hotel room shows a dusting of white ash on my hair.

*The name and exact location of the monastery are withheld out of concerns of further desecration.

Author’s [naïve] question: After decades of actively destroying Armenian cultural and religious sites in Turkey and allowing vandals and treasure hunters to finish the job by digging, drilling, and defacing, is it not time for Turkish authorities to break with past practices and initiate a program aimed at stabilizing structures and preventing further vandalism?

Democracy, Sovereignty and Armenia’s Eurasian Path

As Armenia turns 22 this month, our country finds itself at a

crossroads—perhaps the most defining one in its independent existence.

After four years of negotiations with the European Union (EU) on the

terms of an Association Agreement as part of the Eastern Partnership

program, President Serge Sarkisian last week announced Armenia would

join the Russian-led Customs Union.

The Customs Union of Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and now Armenia will be the foundation of the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) with its own executive body and a single currency. To be launched in January 2015, the EEU is largely seen as Russia’s alternative to the EU.

Surprised by Sarkisian’s political U-Turn, the EU has said that Armenia’s obligations under the Customs Union will be incompatible with those under an Association Agreement that was due to be initiated at a summit in Vilnius in November.

That Sarkisian was subjected to significant pressure to join the Customs Union during his visit to Moscow is unquestionable. No other logical explanation can be provided for his sudden change of heart. Signs of mounting pressure were also apparent in recent months with the dramatic increase of Russian gas prices in Armenia and the sale of Russian weapons to Azerbaijan.

From economic and energy dependence to military reliance, Russia has many pressure points on Armenia. While partly the result of the hostility we have faced from Azerbaijan and Turkey, it is also in large part a consequence of the inability of successive Armenian governments to negotiate a position of mutual benefit in this strategic alliance. In a region where other countries are either outright hostile to Russia or have more subtly yet decisively expressed their inclinations towards Europe, Armenia remains one of Russia’s few allies. In the last two decades, Armenian leaders—both in government and in opposition—have failed to communicate to Russia that this ongoing alliance comes at a cost; and that cost is not the mere survival of Armenia and Nagorno-Karabagh, but rather their growth and prosperity.

Not much is known yet about the EEU and only time will tell what Armenia’s membership in the union will mean for the country’s economy. However, the selection of one union over the other was never only about making an economic choice. The agreement with the EU would have required that Armenia gradually adopt EU regulations and standards. Implemented correctly, these regulations would have contributed to Armenia’s democratization. Moving forward, Sarkisian faces important choices. How he handles Armenia’s membership in the EEU will have significant long-term implications for our country’s democratization and sovereignty.

In the Customs Union, Sarkisian is joined by Nursultan Nazarbayev, the only president Kazakhstan has had since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991; Alexander Lukashenko, the president of Belarus—Europe’s last dictatorship—since 1994; and Vladimir Putin, in power either as president or prime minister since 1999. The length of time these leaders have served should not set an example and a precedent for Armenia too.

Unfortunately, another decision by the Armenian president last week gives rise to serious concern in this regard. One day after his announcement to join the Customs Union, Sarkisian formed a Commission on Constitutional Reform. He justified this decision by the need to “ensure a complete balance of power and increase the efficiency of public administration,” among other things.

Talk of impending constitutional reforms first emerged in late August. The chairman of the National Assembly’s legal affairs committee, Davit Harutiunian, said in an interview with RFE/RL at the time that the leadership is considering adopting a parliamentary system of government. Switching to a parliamentary system has been a demand of several opposition forces in Armenia. With more power vested in the legislature as opposed to the president, a parliamentary system would provide for a more accountable government. There is a catch, however. In the same interview, Harutiunian did not rule out that Sarkisian might lead the Republican Party in the next parliamentary elections and return as prime minister. While the authorities have since tried to water down Harutiunian’s comments, coming from a senior lawmaker in the ruling party they should not be dismissed entirely.

Whether this scenario plays out or not, the government’s track record in democracy already provides reason to fear that partnering with repressive governments will deal a further blow to democracy in Armenia. The authorities’ ongoing crackdown on civil society activists is a case in point. Emboldened by their successful campaign to reverse the 50 percent price hike in public transport, activists have been staging protests against controversial construction projects and most recently against the decision to join the Customs Union. Many protestors have been detained by the police, some on more than one occasion. Several have also been subject to late-night attacks by “unknown assailants.”

The most recent such incident occurred on the evening of Sept. 5, when Suren Saghatelian and Haykak Arshamian were attacked by a group of individuals in downtown Yerevan. They both suffered injuries and were hospitalized as a result. No one has been charged in relation to these attacks, which activists say the government was behind. Activist and lawyer Argishti Kiviryan insisted this was the case during a press conference last week. Himself arrested three times in the past month, Kiviryan accused the authorities of employing the police and criminal elements to try and break the active civic wave the country has been witnessing.

It is against this background that Armenia takes its first steps to join the EEU. How membership in that organization is going to impact Armenia’s democratic process will ultimately be decided by the country’s leadership. If it was the safeguarding of vital national interests in the face of significant Russian pressure that pushed Yerevan towards the Eurasian option, that choice must not dictate the fate of democracy in Armenia. The authorities must marry membership in the Customs Union with a commitment to democracy.

At the same time, the authorities must muster the political astuteness necessary to uphold Armenia’s sovereignty within the union. As Russia struggles to get other key countries such as Ukraine on board, Armenia should use its status as one of the few members in this club to remind Russia that this is a relationship of mutual need. After all, beyond the concept, Russia’s union will only be viable if it has members.

The Customs Union of Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and now Armenia will be the foundation of the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) with its own executive body and a single currency. To be launched in January 2015, the EEU is largely seen as Russia’s alternative to the EU.

Surprised by Sarkisian’s political U-Turn, the EU has said that Armenia’s obligations under the Customs Union will be incompatible with those under an Association Agreement that was due to be initiated at a summit in Vilnius in November.

That Sarkisian was subjected to significant pressure to join the Customs Union during his visit to Moscow is unquestionable. No other logical explanation can be provided for his sudden change of heart. Signs of mounting pressure were also apparent in recent months with the dramatic increase of Russian gas prices in Armenia and the sale of Russian weapons to Azerbaijan.

From economic and energy dependence to military reliance, Russia has many pressure points on Armenia. While partly the result of the hostility we have faced from Azerbaijan and Turkey, it is also in large part a consequence of the inability of successive Armenian governments to negotiate a position of mutual benefit in this strategic alliance. In a region where other countries are either outright hostile to Russia or have more subtly yet decisively expressed their inclinations towards Europe, Armenia remains one of Russia’s few allies. In the last two decades, Armenian leaders—both in government and in opposition—have failed to communicate to Russia that this ongoing alliance comes at a cost; and that cost is not the mere survival of Armenia and Nagorno-Karabagh, but rather their growth and prosperity.

Not much is known yet about the EEU and only time will tell what Armenia’s membership in the union will mean for the country’s economy. However, the selection of one union over the other was never only about making an economic choice. The agreement with the EU would have required that Armenia gradually adopt EU regulations and standards. Implemented correctly, these regulations would have contributed to Armenia’s democratization. Moving forward, Sarkisian faces important choices. How he handles Armenia’s membership in the EEU will have significant long-term implications for our country’s democratization and sovereignty.

In the Customs Union, Sarkisian is joined by Nursultan Nazarbayev, the only president Kazakhstan has had since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991; Alexander Lukashenko, the president of Belarus—Europe’s last dictatorship—since 1994; and Vladimir Putin, in power either as president or prime minister since 1999. The length of time these leaders have served should not set an example and a precedent for Armenia too.

Unfortunately, another decision by the Armenian president last week gives rise to serious concern in this regard. One day after his announcement to join the Customs Union, Sarkisian formed a Commission on Constitutional Reform. He justified this decision by the need to “ensure a complete balance of power and increase the efficiency of public administration,” among other things.

Talk of impending constitutional reforms first emerged in late August. The chairman of the National Assembly’s legal affairs committee, Davit Harutiunian, said in an interview with RFE/RL at the time that the leadership is considering adopting a parliamentary system of government. Switching to a parliamentary system has been a demand of several opposition forces in Armenia. With more power vested in the legislature as opposed to the president, a parliamentary system would provide for a more accountable government. There is a catch, however. In the same interview, Harutiunian did not rule out that Sarkisian might lead the Republican Party in the next parliamentary elections and return as prime minister. While the authorities have since tried to water down Harutiunian’s comments, coming from a senior lawmaker in the ruling party they should not be dismissed entirely.

Whether this scenario plays out or not, the government’s track record in democracy already provides reason to fear that partnering with repressive governments will deal a further blow to democracy in Armenia. The authorities’ ongoing crackdown on civil society activists is a case in point. Emboldened by their successful campaign to reverse the 50 percent price hike in public transport, activists have been staging protests against controversial construction projects and most recently against the decision to join the Customs Union. Many protestors have been detained by the police, some on more than one occasion. Several have also been subject to late-night attacks by “unknown assailants.”

The most recent such incident occurred on the evening of Sept. 5, when Suren Saghatelian and Haykak Arshamian were attacked by a group of individuals in downtown Yerevan. They both suffered injuries and were hospitalized as a result. No one has been charged in relation to these attacks, which activists say the government was behind. Activist and lawyer Argishti Kiviryan insisted this was the case during a press conference last week. Himself arrested three times in the past month, Kiviryan accused the authorities of employing the police and criminal elements to try and break the active civic wave the country has been witnessing.

It is against this background that Armenia takes its first steps to join the EEU. How membership in that organization is going to impact Armenia’s democratic process will ultimately be decided by the country’s leadership. If it was the safeguarding of vital national interests in the face of significant Russian pressure that pushed Yerevan towards the Eurasian option, that choice must not dictate the fate of democracy in Armenia. The authorities must marry membership in the Customs Union with a commitment to democracy.

At the same time, the authorities must muster the political astuteness necessary to uphold Armenia’s sovereignty within the union. As Russia struggles to get other key countries such as Ukraine on board, Armenia should use its status as one of the few members in this club to remind Russia that this is a relationship of mutual need. After all, beyond the concept, Russia’s union will only be viable if it has members.

Kurdish Leaders Apologize for Genocide During Monument Inauguration in Diyarbakir

DIYARBAKIR, Turkey (A.W.)—The Sur Municipality of Diyarbakir held the

official inauguration of the Monument of Common Conscience on Sept. 12,

with mayor Abdullah Demirbaş apologizing in the name of Kurds for the

Armenian and Assyrian “massacre and deportations.”

“We Kurds, in the name of our ancestors, apologize for the massacres and deportations of the Armenians and Assyrians in 1915,” Demirbaş declared in his opening speech. “We will continue our struggle to secure atonement and compensation for them.”

The mayor called upon the Turkish authorities to issue an apology and do whatever needed to atone for the genocide. “We invite them to take steps in this direction,” he said.

The inscription on the monument at the Anzele Park, near a recently restored historic fountain, reads, in six languages including Armenian: We share the pain so that it is not repeated.

“This memorial is dedicated to all peoples and religious groups who were subjected to massacres in these lands,” Demirbaş said. “The Monument of Common Conscience was erected to remember and demand accountability for all the massacres that took place since 1915.”

Demirbaş noted that the monument remembers all the Armenians, Assyrians, Jews, Yezidis, Alevis who were subjected to massacres, as well as all the Sunni who “stood against the system.”

Representatives of the Armenian, Assyrian, Alevi, and Sunni communities also spoke at the opening event. Diyarbakir Armenian writer Mgrditch Margosyan welcomed the opening of the memorial, noting that he awaits the steps that would follow.

Zahit Çiftkuran, head of the Diyarbakir association of the clergy, recounted the story of a man who, while walking by a restaurant, notices the following sign: “You eat, your grandchildren pay the bill.” Enthused by the promise of free lunch, the man goes in and orders food. Soon, they bring him an expensive bill. “But I was not supposed to pay! Where did this bill come from?” the man asks. The owner of the restaurant responds: “This is not your bill. It is your grandfather’s!”

Çiftkuran concluded, “Today, we have to pay for what our grandparents have done.”

An earlier version of this article had misquoted Demirbaş as having used the term “genocide.” Our correspondent later revised the quote. Demirbaş had used “massacres and deportations” when referring to the Genocide.

“We Kurds, in the name of our ancestors, apologize for the massacres and deportations of the Armenians and Assyrians in 1915,” Demirbaş declared in his opening speech. “We will continue our struggle to secure atonement and compensation for them.”

The mayor called upon the Turkish authorities to issue an apology and do whatever needed to atone for the genocide. “We invite them to take steps in this direction,” he said.

The inscription on the monument at the Anzele Park, near a recently restored historic fountain, reads, in six languages including Armenian: We share the pain so that it is not repeated.

“This memorial is dedicated to all peoples and religious groups who were subjected to massacres in these lands,” Demirbaş said. “The Monument of Common Conscience was erected to remember and demand accountability for all the massacres that took place since 1915.”

Demirbaş noted that the monument remembers all the Armenians, Assyrians, Jews, Yezidis, Alevis who were subjected to massacres, as well as all the Sunni who “stood against the system.”

Representatives of the Armenian, Assyrian, Alevi, and Sunni communities also spoke at the opening event. Diyarbakir Armenian writer Mgrditch Margosyan welcomed the opening of the memorial, noting that he awaits the steps that would follow.

Zahit Çiftkuran, head of the Diyarbakir association of the clergy, recounted the story of a man who, while walking by a restaurant, notices the following sign: “You eat, your grandchildren pay the bill.” Enthused by the promise of free lunch, the man goes in and orders food. Soon, they bring him an expensive bill. “But I was not supposed to pay! Where did this bill come from?” the man asks. The owner of the restaurant responds: “This is not your bill. It is your grandfather’s!”

Çiftkuran concluded, “Today, we have to pay for what our grandparents have done.”

An earlier version of this article had misquoted Demirbaş as having used the term “genocide.” Our correspondent later revised the quote. Demirbaş had used “massacres and deportations” when referring to the Genocide.

Mass Celebrated at Sourp Giragos Church in Diyarbakir

Hundreds attended a church service at the Sourp Giragos Church. (Photo by Gulisor Akkum, The Armenian Weekly)

Two days earlier, on Sun., Sept. 8, a church service was held at the Sourp Khatch Church on Aghtamar Island in Van, during which five Armenians were baptized.

The head of the Sourp Giragos Church Foundation, Vartkes Ergun Ayık, told the Armenian Weekly that the two services were held two days apart to maximize attendance.

Acting Patriarch Aram Ateshyan conducted the church services, as Sourp Giragos does not yet have a priest.

“Unfortunately, there is no institution for training clergy in Turkey, which is why two years ago an Armenian from Adiyaman [in Turkey] was sent to study abroad. Upon the completion of his education, he will be assigned as permanent pastor at Sourp Giragos,” Ayık told the Weekly.

The church service was also attended by Mayors Osman Baydemir and Abdullah Demirbas, the heads of the Diyarbakir Metropolitan Municipality and the Sour Municipality, respectively.

“The Armenian people was burnt into ashes in 1915. Today, the Armenians are rising from the ashes in these lands,” Demirbas told the Weekly.

Sourp Giragos was restored and opened for worship in 2011 through the efforts of a handful of Armenian supporters and the Diyarbakir municipal authorities

Armenians Celebrate First Baptisms at Aghtamar Since 1915

Special to the Armenian Weekly

For the first time since 1915, the Armenian Church performed the rite of baptism at the Church of the Holy Cross (Sourp Khatch) on Aghtamar Island in Lake Van.

Two adults and three youths, including a boy from Armenia named Van

and three Armenians from the town of Van, were baptized. The identity of

the fifth person to be baptized wasn’t immediately clear. She had made

her way to the altar during the ceremony and announced that she wished

to be baptized. The church honored her impromptu request.

The five baptisms were conducted on Sept. 8 at the conclusion of a church service—itself a rare event at Aghtamar—that had drawn more than 1,000 visitors from around the world. The Divine Liturgy, which Armenians refer to as the Badarak, has been performed only once each year at Aghtamar since 2010, after a genocide-induced hiatus of 95 years.

Bartev Karakeshian, a parish priest from Sydney, Australia, was among six visitors from his parish who made the pilgrimage to Aghtamar for the ceremony.

“We came just for this event,” he told me. All 6 people in his group had traveled 25 hours solely for the purpose of attending the Aghtamar ceremony as pilgrims. But when Father Bartev arrived at Aghtamar, the other clergy recognized him as a former member of the Istanbul Armenian community, and they invited him to participate in the ceremony. So, he said, “I read the confession, and gave the communion.”

A photograph of him standing at the altar and reading the confession

appeared in a major Turkish daily newspaper the next morning. The daily

newspaper of Van printed a photograph of Father Bartev administering

communion. For a moment, and by chance, Father Bartev had become famous.

In Turkey, press coverage of the baptisms, both before and after the ceremony, appeared to be matter-of-fact. The media largely announced the event without an expression of opinion.

But some in Turkey were opinionated, and a small group of Turks protested the baptisms on the morning of the event. Turkish police, who had a significant presence on and around the island of Aghtamar, did not allow the protesters to board boats to the island. The day concluded peacefully, without any significant incidents, and the protests of the Turkish group went unheard by most.

Rosine Dilanian was one of the six Armenians who traveled to Aghtamar from Sydney. This was the first trip to Aghtamar for each person in her group. “This was a dream for us,” she said. “We have all been to Armenia, but not this part of Armenia,” she added.

I spoke to groups of pilgrims on the island after the ceremony. I

encountered Armenians from Yerevan and Istanbul who had traveled here

expressly for this event. I met the group from Australia. I also spoke

with a woman from Los Angeles who, as with the others, had traveled to

Aghtamar solely because of the Liturgy. Raffi Hovhannissian, the

presidential candidate and former Foreign Minister of Armenia, was also

present.

The Armenians whom I met from Yerevan had traveled through Georgia to get past the closed Turkish-Armenian border. The Armenians from Istanbul told me, through an interpreter, that they couldn’t speak any Armenian. They explained, in Turkish, that they had flown to Van from Istanbul for the ceremony and that they would stay just one night.

By late afternoon, most of the Armenians appeared to have left the island, and the remaining visitors were Kurds, for whom Aghtamar is a picnic destination, rather than a holy site of great significance.

I watched the progression of the crowds all day long. I had been one of the first people on the island that day, at about 8 a.m. I departed on the last boat at 7 p.m.

During my 11 hours on the island, I enjoyed being able to publicly celebrate my heritage, and to exercise a privilege that is rarely available in the lands of historic Armenia. I had traveled here to do research and photography for a book about historic Armenia—a sequel, of sorts, to my current book, Armenia and Karabakh: The Stone Garden Travel Guide.

The Church of the Holy Cross is commonly known as Aghtamar because of its location on Aghtamar Island. The site was abandoned during the Armenian Genocide. During the decades that followed, this unique 10th-century cathedral fell into ruin and was vandalized.

After ignoring the problem for nearly a century, in 2007 the Turkish government completed repairs to the cathedral. The building was opened as a museum, and since 2010 the Armenian Church has been allowed to conduct a Divine Liturgy, or Badarak, once yearly. The ceremony that was conducted on Sept. 8 was the fourth that has been allowed since 1915.

The woman who was baptized on this day along with her two daughters

was an Armenian living in Van. Her family had been forcibly converted to

Islam after the genocide. She is one of the so-called “hidden

Armenians” of the region.

“But they knew they were Armenians,” said Father Bartev, the pilgrim from Sydney. “They kept saying, ‘We are Armenians, We are Armenians.’” Among all of the Armenians at Aghtamar that day, their journey was the shortest, but also the most difficult.

Van, the teenage boy from Yerevan, was brought here to be baptized by his father. “His dream was to come to Aghtamar,” said Father Bartev.

The Liturgy began at 10:30 a.m. and lasted about two hours. The baptisms were conducted immediately following the Liturgy with a ceremony that lasted about 30 minutes. At the conclusion of the baptism, the clergy formed a processional outside to the courtyard, where they joined the pilgrims in singing hymns. The Liturgy was conducted by the acting head of the Armenian Patriarchate of Istanbul, Aram Ateshyan.

Several hours after the baptisms, the sun had stopped shining on Aghtamar and the last boat back to shore was ready to depart. All but a handful of the 1,000 visitors had long gone. As I boarded the boat back to Van, I anticipated another year-long hibernation of Armenian culture on Aghtamar. But I was happy that for one long day, the sun had shined bright.

Matthew Karanian practices law in Pasadena, Calif. He is the author of Armenia and Karabakh: The Stone Garden Travel Guide, the best-selling book about Armenia in the U.S. Armenia and Karabakh is the winner of three national book awards and was featured in the Los Angeles Times, which praised the book as “a fresh view on ancient Armenia.” The book includes photography by Robert Kurkjian and is available for $25 from www.ArmeniaTravelGuide.com, from independent Armenian booksellers, and from Barnes and Noble.

For the first time since 1915, the Armenian Church performed the rite of baptism at the Church of the Holy Cross (Sourp Khatch) on Aghtamar Island in Lake Van.

A crowd of pilgrims gathers outside the

Church of the Holy Cross at Aghtamar, following the first baptism at the

church since 1915. (Photo by Matthew Karanian)

The five baptisms were conducted on Sept. 8 at the conclusion of a church service—itself a rare event at Aghtamar—that had drawn more than 1,000 visitors from around the world. The Divine Liturgy, which Armenians refer to as the Badarak, has been performed only once each year at Aghtamar since 2010, after a genocide-induced hiatus of 95 years.

Bartev Karakeshian, a parish priest from Sydney, Australia, was among six visitors from his parish who made the pilgrimage to Aghtamar for the ceremony.

“We came just for this event,” he told me. All 6 people in his group had traveled 25 hours solely for the purpose of attending the Aghtamar ceremony as pilgrims. But when Father Bartev arrived at Aghtamar, the other clergy recognized him as a former member of the Istanbul Armenian community, and they invited him to participate in the ceremony. So, he said, “I read the confession, and gave the communion.”

Clergy gather in the courtyard outside

the Church of the Holy Cross at Aghtamar following the Badarak on Sept.

8. (Photo by Matthew Karanian)

In Turkey, press coverage of the baptisms, both before and after the ceremony, appeared to be matter-of-fact. The media largely announced the event without an expression of opinion.

But some in Turkey were opinionated, and a small group of Turks protested the baptisms on the morning of the event. Turkish police, who had a significant presence on and around the island of Aghtamar, did not allow the protesters to board boats to the island. The day concluded peacefully, without any significant incidents, and the protests of the Turkish group went unheard by most.

Rosine Dilanian was one of the six Armenians who traveled to Aghtamar from Sydney. This was the first trip to Aghtamar for each person in her group. “This was a dream for us,” she said. “We have all been to Armenia, but not this part of Armenia,” she added.

Sourp Khatch at Aghtamar Island on the evening of Sept. 8, after the annual Badarak. (Photo by Matthew Karanian)

The Armenians whom I met from Yerevan had traveled through Georgia to get past the closed Turkish-Armenian border. The Armenians from Istanbul told me, through an interpreter, that they couldn’t speak any Armenian. They explained, in Turkish, that they had flown to Van from Istanbul for the ceremony and that they would stay just one night.

By late afternoon, most of the Armenians appeared to have left the island, and the remaining visitors were Kurds, for whom Aghtamar is a picnic destination, rather than a holy site of great significance.

I watched the progression of the crowds all day long. I had been one of the first people on the island that day, at about 8 a.m. I departed on the last boat at 7 p.m.

During my 11 hours on the island, I enjoyed being able to publicly celebrate my heritage, and to exercise a privilege that is rarely available in the lands of historic Armenia. I had traveled here to do research and photography for a book about historic Armenia—a sequel, of sorts, to my current book, Armenia and Karabakh: The Stone Garden Travel Guide.

The Church of the Holy Cross is commonly known as Aghtamar because of its location on Aghtamar Island. The site was abandoned during the Armenian Genocide. During the decades that followed, this unique 10th-century cathedral fell into ruin and was vandalized.

After ignoring the problem for nearly a century, in 2007 the Turkish government completed repairs to the cathedral. The building was opened as a museum, and since 2010 the Armenian Church has been allowed to conduct a Divine Liturgy, or Badarak, once yearly. The ceremony that was conducted on Sept. 8 was the fourth that has been allowed since 1915.

Two young women from Van are baptized at

Sourp Khatch, the Church of the Holy Cross, at Aghtamar on Sept. 8.

Three others were also baptized that day during the same ceremony.

(Photo by Matthew Karanian)

“But they knew they were Armenians,” said Father Bartev, the pilgrim from Sydney. “They kept saying, ‘We are Armenians, We are Armenians.’” Among all of the Armenians at Aghtamar that day, their journey was the shortest, but also the most difficult.

Van, the teenage boy from Yerevan, was brought here to be baptized by his father. “His dream was to come to Aghtamar,” said Father Bartev.

The Liturgy began at 10:30 a.m. and lasted about two hours. The baptisms were conducted immediately following the Liturgy with a ceremony that lasted about 30 minutes. At the conclusion of the baptism, the clergy formed a processional outside to the courtyard, where they joined the pilgrims in singing hymns. The Liturgy was conducted by the acting head of the Armenian Patriarchate of Istanbul, Aram Ateshyan.

Several hours after the baptisms, the sun had stopped shining on Aghtamar and the last boat back to shore was ready to depart. All but a handful of the 1,000 visitors had long gone. As I boarded the boat back to Van, I anticipated another year-long hibernation of Armenian culture on Aghtamar. But I was happy that for one long day, the sun had shined bright.

Matthew Karanian practices law in Pasadena, Calif. He is the author of Armenia and Karabakh: The Stone Garden Travel Guide, the best-selling book about Armenia in the U.S. Armenia and Karabakh is the winner of three national book awards and was featured in the Los Angeles Times, which praised the book as “a fresh view on ancient Armenia.” The book includes photography by Robert Kurkjian and is available for $25 from www.ArmeniaTravelGuide.com, from independent Armenian booksellers, and from Barnes and Noble.

Sassounian: Millions Watch Popular Egyptian Talk Show on the Armenian Genocide

Ever since Egypt’s President Mohamed Morsi was removed from office,

Turkey’s Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been harshly critical

of the new government, strongly advocating his fellow Islamist Morsi’s

return to power.

Given Erdogan’s unwelcome meddling in Egypt’s internal affairs, millions of Egyptians have expressed anger and resentment against Turkey and its prime minister. Egyptian newspapers have been replete with anti-Turkish reports and commentaries. Dozens of articles have been published condemning Turkish denials of the Armenian Genocide and urging Egypt’s new leaders to recognize it. There have also been calls for erecting a monument for the Armenian Genocide in Cairo and demands that Turkey pay restitution for the Armenian victims. In an unprecedented move, attorney Muhammad Saad Khairallah, head of the Institute of the Popular Front in Egypt, filed a lawsuit accusing Turkey of committing genocide against Armenians.

On Sept. 4, Khairallah and Dr. Ayman Salama, Professor of International Law at Cairo University, appeared on Lilian Daoud’s highly popular talk show, Al-Soura al-Kamila (The Complete Picture) on ONtv, watched by millions in Egypt and throughout the Arab world. Participating in the show by phone were Resul Tosun, former Turkish Parliament member from Erdogan’s Islamist AK Party, and Harut Sassounian, Publisher of The California Courier. The 36-minute TV program was conducted in Arabic, a language I have rarely used since childhood.

Prof. Salama informed the audience that the Turkish Military Tribunal in 1919 indicted the criminals responsible for the Armenian Genocide. Seventeen Turkish officials were found guilty, and three were hanged. Dr. Salama indicated that France, Great Britain and Russia had issued a joint Declaration in 1915, warning that they would hold Turkish leaders responsible for massacring Armenians and committing “crimes against humanity and civilization.”

Attorney Khairallah insisted that raising the Armenian Genocide issue in Egypt is long overdue and does not have any political undertones. He hoped that his lawsuit will force Egypt, “the largest Sunni country in the Middle East,” to serve as an example for other Arab countries to acknowledge the Armenian Genocide. Khairallah announced that his lawsuit will be considered by the Egyptian Court on November 5. He hoped that the Court would make a historic decision regarding this critical “human rights issue.”

When the hostess of the TV show asked for my opinion on the Egyptian lawsuit, I expressed my great satisfaction, hoping for a positive verdict on the eve of the Centennial of the Armenian Genocide, and looking forward to its recognition by the Egyptian government.

I also commented that Erdogan had anointed himself as the new Sultan of the Middle East, and sole defender of all Muslims, Arabs and Palestinians. However, Erdogan’s misrepresentation was finally exposed when the Arab world realized that he was simply trying to dominate the region, pursuing Turkey’s self-interest rather than that of Arabs and Muslims.

Former Turkish parliament member Resul Tosun, joining the show by phone, quickly antagonized the viewers by claiming that “the current Egyptian government that came to power after the military coup is not legitimate, therefore, the filed lawsuit cannot be considered legitimate.” Tosun then went on to parrot his Turkish bosses’ baseless denials of the Armenian Genocide.

Prof. Salama, incensed by Tosun’s remarks, called Erdogan “the successor of the Ottoman butchers who committed the Armenian Genocide.”

The TV hostess then asked for my reaction to Tosun’s perverted views on the Armenian Genocide. I reminded the viewers that Kemal Ataturk, in an interview published in the ‘Los Angeles Examiner’ on August 1, 1926, had demanded that the Young Turks be “made to account for the lives of millions of our Christian subjects who were ruthlessly driven en masse and massacred.” I also recalled that the Sheikh of Al-Azhar, leader of the globally preeminent center of Islamic studies in Cairo, had issued a Fatwa (religious decree) in 1909 chastising Turkish officials for massacring 30,000 Armenians in Adana, Cilicia.

At the end of the show, attorney Khairallah announced that public rallies will be held shortly to demonstrate that his group’s lawsuit emanates from a popular demand–Egyptians asking their government “to recognize that Armenians were massacred at the hands of Turkish criminals.”

So far, Lebanon is the only Arab country to have recognized the Armenian Genocide. If Egypt follows suit, can Syria and the rest of the Arab world be far behind?

Given Erdogan’s unwelcome meddling in Egypt’s internal affairs, millions of Egyptians have expressed anger and resentment against Turkey and its prime minister. Egyptian newspapers have been replete with anti-Turkish reports and commentaries. Dozens of articles have been published condemning Turkish denials of the Armenian Genocide and urging Egypt’s new leaders to recognize it. There have also been calls for erecting a monument for the Armenian Genocide in Cairo and demands that Turkey pay restitution for the Armenian victims. In an unprecedented move, attorney Muhammad Saad Khairallah, head of the Institute of the Popular Front in Egypt, filed a lawsuit accusing Turkey of committing genocide against Armenians.

On Sept. 4, Khairallah and Dr. Ayman Salama, Professor of International Law at Cairo University, appeared on Lilian Daoud’s highly popular talk show, Al-Soura al-Kamila (The Complete Picture) on ONtv, watched by millions in Egypt and throughout the Arab world. Participating in the show by phone were Resul Tosun, former Turkish Parliament member from Erdogan’s Islamist AK Party, and Harut Sassounian, Publisher of The California Courier. The 36-minute TV program was conducted in Arabic, a language I have rarely used since childhood.

Prof. Salama informed the audience that the Turkish Military Tribunal in 1919 indicted the criminals responsible for the Armenian Genocide. Seventeen Turkish officials were found guilty, and three were hanged. Dr. Salama indicated that France, Great Britain and Russia had issued a joint Declaration in 1915, warning that they would hold Turkish leaders responsible for massacring Armenians and committing “crimes against humanity and civilization.”

Attorney Khairallah insisted that raising the Armenian Genocide issue in Egypt is long overdue and does not have any political undertones. He hoped that his lawsuit will force Egypt, “the largest Sunni country in the Middle East,” to serve as an example for other Arab countries to acknowledge the Armenian Genocide. Khairallah announced that his lawsuit will be considered by the Egyptian Court on November 5. He hoped that the Court would make a historic decision regarding this critical “human rights issue.”

When the hostess of the TV show asked for my opinion on the Egyptian lawsuit, I expressed my great satisfaction, hoping for a positive verdict on the eve of the Centennial of the Armenian Genocide, and looking forward to its recognition by the Egyptian government.

I also commented that Erdogan had anointed himself as the new Sultan of the Middle East, and sole defender of all Muslims, Arabs and Palestinians. However, Erdogan’s misrepresentation was finally exposed when the Arab world realized that he was simply trying to dominate the region, pursuing Turkey’s self-interest rather than that of Arabs and Muslims.

Former Turkish parliament member Resul Tosun, joining the show by phone, quickly antagonized the viewers by claiming that “the current Egyptian government that came to power after the military coup is not legitimate, therefore, the filed lawsuit cannot be considered legitimate.” Tosun then went on to parrot his Turkish bosses’ baseless denials of the Armenian Genocide.

Prof. Salama, incensed by Tosun’s remarks, called Erdogan “the successor of the Ottoman butchers who committed the Armenian Genocide.”

The TV hostess then asked for my reaction to Tosun’s perverted views on the Armenian Genocide. I reminded the viewers that Kemal Ataturk, in an interview published in the ‘Los Angeles Examiner’ on August 1, 1926, had demanded that the Young Turks be “made to account for the lives of millions of our Christian subjects who were ruthlessly driven en masse and massacred.” I also recalled that the Sheikh of Al-Azhar, leader of the globally preeminent center of Islamic studies in Cairo, had issued a Fatwa (religious decree) in 1909 chastising Turkish officials for massacring 30,000 Armenians in Adana, Cilicia.

At the end of the show, attorney Khairallah announced that public rallies will be held shortly to demonstrate that his group’s lawsuit emanates from a popular demand–Egyptians asking their government “to recognize that Armenians were massacred at the hands of Turkish criminals.”

So far, Lebanon is the only Arab country to have recognized the Armenian Genocide. If Egypt follows suit, can Syria and the rest of the Arab world be far behind?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)