Reflections on a Groundbreaking Conference in Istanbul

In early November, the Hrant Dink Foundation held a conference on

“Islamicized Armenians” at the Istanbul Bosphorus University, breaking

one more taboo in Turkey. Islamicized Armenians were hitherto a hidden

reality, a secret known by many, but which couldn’t be revealed to

anyone, whispered behind closed doors but filed in government

intelligence offices, and it finally broke free into the public.

The late Hrant Dink would have been elated to see this conference

become a reality, eight years after the first conference on “Armenians

during the late Ottoman Empire era and the 1915 events” was held at

Istanbul Bilgi University, when protesters hurled insults at the

conference participants and government ministers labelled them as

“traitors stabbing Turks in the back.” That conference had also broken a

taboo, but Hrant was already a marked man for revealing the identity of

the most famous Islamicized Armenian—Sabiha Gokcen, Ataturk’s adopted

daughter and the first female Turkish combat pilot, who was an Armenian

orphan named Hatun Sebilciyan.

It is a known fact that in 1915, tens of thousands of Armenian

orphans were forcibly Islamicized and Turkified; that tens of thousands

of Armenian girls and young women were captured by Kurds and Turks as

slaves, maids, or wives; that tens of thousands Armenians converted to

Islam to escape the deportations and massacres; and that tens of

thousands of Armenians found shelter in friendly Kurdish and Alevi

villages, but lost their identity. What happened to these survivors,

these living victims of the 1915 genocide? Hrant was obsessed with them:

“We keep talking about the ones ‘gone’ in 1915. Let us start talking

about the ones who ‘remained.’”

These remaining people survived, but mostly in living hells.

Remarkably, their children and grandchildren are now “coming out,” are

no longer hiding their Armenian roots. One of the first was the famous

Turkish lawyer Fethiye Cetin, who revealed that her grandmother was

Armenian, in her book My Grandmother. This was followed by another book edited by Aysegul Altinay and Fethiye Cetin, titled The Grandchildren,

about dozens of Turkish/Kurdish people describing their Armenian roots,

without revealing their real identities. Then came the reconstruction

of the Surp Giragos Armenian Church in Diyarbakir/Dikranagerd, which

became a destination for many hidden Armenians in Eastern Anatolia. On

average, over a hundred people visit the church daily, most of them

hidden Armenians. Some come to pray, get baptized, or married, but most

just visit to feel Armenian, without converting back to Christianity.

This has created a new identity of Muslim Armenians, in addition to

the historical and traditional identity of Christian Armenians. In a

country where only Muslim Turks can work for the government, where being

non-Muslim is sufficient excuse for persecution, harassment and

attacks, where the word Armenian is used as the biggest insult, it takes

real courage for someone to reveal that he is now an Armenian and no

longer a Turk/Kurd/Muslim. People can easily lose their jobs,

livelihood, or even lives for changing their identity. As an example of

the level of racism and discrimination in the country, an

ultra-nationalist opposition member of parliament years ago accused

Turkish President Abdullah Gul of having Armenian roots in his family

from Kayseri. Gul sued her for defamation, and the courts sided with

him, ordering her to pay compensation for such an insult.

It is difficult to estimate the number of Islamicized Armenians in

Turkey, and even more difficult to predict what proportion of them are

aware of their Armenian roots, or how many are willing to regain their

Armenian identity. Based on independent studies of the 1915 events, one

can conclude that more than 100,000 orphans were forcibly

Islamicized/Turkified, and that another 200,000 Armenians survived by

converting to Islam or by finding shelter in friendly Kurdish and Alevi

regions. It is therefore conceivable that 300,000 souls survived as

Muslims. The population of Turkey has increased seven fold since then;

using the same multiple, one can extrapolate that there may be two

million people with Armenian roots in Turkey today, originating from the

1915 survivors. There were even more widespread conversions to Islam

during the 1894-96 massacres, when entire villages were forcibly

Islamicized. A couple centuries before, Hamshen Armenians were

Islamicized in northeast Anatolia. The Muslim Hamshentsis,

numbering about 500,000, speak a dialect based on Armenian, but had

never identified themselves as Armenian, until recently. Adding all

these forced conversions prior to and during 1915, one can conclude that

the number of people with Armenian roots in present-day Turkey reaches

several million. (The numbers are difficult to accurately estimate, but

in any case, they easily exceed the present population of Armenia.)

The reality is that the secrets of “Armenianness” whispered for three

or four generations after 1915 are now becoming loud revelations of new

identities. As evidenced in the recent conference, even Hamshen

Armenians have started exploring and reclaiming their long lost roots.

During the reconstruction of the Surp Giragos Church and in my travels

in eastern and southeastern Anatolia, one out of every three Kurds that I

met had an Armenian grandmother in the family. This fact, hidden until

recently, is now revealed openly, often leading young generations to

reclaim their Armenian identities, but without giving up Islam. One

interesting observation is that the hidden Armenians were aware of other

hidden ones and all attempted to intermarry, resulting in many couples

who ended up having Armenian roots from both parents.

The conference attracted numerous academicians, historians, and

journalists from both within and outside Turkey, as well as dozens of

presenters of oral history. One of the most dramatic presentations was

about Sara, a 15-year-old Armenian girl from Urfa Viranshehir, who was

captured by the Turkish strongman of the region, Eyup Aga. Eyup wanted

to take Sara as his third wife. When Sara refused, Eyup killed her

mother. When Sara refused again, Eyup killed her father. When Eyup

threatened to kill Sara’s little brother, Sara couldn’t resist any more,

and married the killer of her parents, on the condition that her

brother be spared and she be allowed to keep her name. But her brother

was also eventually killed. As she resisted Eyup’s advances, she was

repeatedly raped and was pregnant 15 times, giving birth to 15 babies,

who all died prematurely. Eyup constantly tortured her, even marking a

cross in her body with a knife. His family also mistreated her, viewing

her as an outcast, and she had a hellish life to the end. At the end of

the story, the presenter, a Turkish academician, revealed that Eyup and

the family who committed these crimes against Sara was her own family.

Her final statement was even more dramatic than the story: “We always

hear stories told by the victims. It is now time for the perpetrators to

start talking about and owning their crimes.”

There are new revelations about how the Turkish government kept tabs

on Islamicized Armenians. Apparently, the government kept records of

every Armenian village or large Armenian clan that was forcibly

Islamicized in 1915. It was recently discovered that the identification

cards of hidden or known Armenians had a special numbering system to

secretly identify them. There are anecdotes that a few Turkish

candidates for air force pilot positions were turned away even though

they qualified after rigorous tests, when government records revealed

that they come from Islamicized Armenian families.

It is of greater concern to us how the Islamicized Armenians are

being dealt with by Armenians. It seems that the Istanbul Armenian

community and, more critically, the Istanbul Armenian Patriarchate are

unable or unwilling to accept the hidden Armenians coming out as

Armenians, unless these people accept Christianity, get baptized, and

learn to speak Armenian. But it is unrealistic to expect the new

Armenians to comply with these requirements. Since Armenians in Turkey

are all defined as belonging to the Armenian Church, if the newcomers

are rejected by the Patriarchate, they become double outcasts, not only

from their previous Muslim Turkish/Kurdish community, but also from the

Armenian community, as they cannot get married, baptized, or buried by

the church and cannot send their children to Armenian schools. If they

have made a conscious decision to identify themselves as Armenian—a

risky and dangerous initiative under the present circumstances—they

should be readily accepted as Armenians, regardless of whether they stay

Muslim or atheist or anything else. Relationships get even more

complicated as there are now many families with one branch carrying on

life as Muslim Turks/Kurds, another branch as Muslim Armenian, and a

third branch as Christian Armenian. The Etchmiadzin Church in Armenia is

more tolerant, and has issued the following statement: “Common

ethnicity, land, language, history, cultural heritage, and religion are

general measures in defining a nation. Even if one or more of these

measures can be missing due to historic reasons, such as the inability

to speak the language, or practice the religion, or the lack of

knowledge of cultural and historic heritage, this should not be used to

exclude one’s Armenian identity.” Yet, Charles Aznavour’s approach is

the most welcoming: “Armenia should embrace the Islamicized Armenians

and open its doors to them.”

After Armenia, Karabagh, and the Armenian Diaspora, there is now an emerging fourth

Armenian world—the Islamicized Armenians of Turkey. Accepting this new

reality will help both Turks and Armenians understand the realities and

consequences of 1915.

Tuesday, November 19, 2013

Armenians of China Celebrate Opening of ‘Maxian Hong Kong Armenian Center’

HONG KONG—On Sat., Nov. 9, the Armenian community of China, known as

“ChinaHay,” along with more than 100 guests, including many from

overseas, gathered in Hong Kong to attend the official opening ceremony

of the newly established Jack & Julie Maxian Hong Kong Armenian

Center.

Honorary guests included His Holiness Karekin II, Supreme Patriarch and Catholicos of All Armenians; His Grace Bishop Haigazoun Najarian, Primate of the Diocese of Australia and New Zealand; His Eminence Archbishop Aram Ateshian, Patriarchal Vicar of Constantinople; His Excellency the Armenian Ambassador to China, Armen Sargsyan; and the Honorary Consul of Armenia to Thailand, Arto Artinian.

The two-day celebration began with a ribbon-cutting ceremony followed by the blessing given by Catholicos Karekin II at the beautiful center altar built especially for religious events. “Armenian couples will marry here, and Armenian kids will be baptized in this house,” Jack Maxian said in his welcoming speech. “We will arrange Armenian meetings in this center, festivities devoted to Armenian culture, and foreigners will be surprised that the Armenian people are able to build an Armenian house outside of their own land.”

That evening, Catholicos Karekin II granted the St. Nerses Shnorhali Medal of Honor to Mr. and Mrs. Maxian for their devotion to the nation. “We are happy to see that Armenian national identity is so well preserved in a remote country like China, despite the small size of the community,” he said. His Holiness also visited the grave of Sir Paul Catchik Chater, likely the most famous Armenian in Asia, who moved to Hong Kong in 1864 from Calcutta India and became one of the most successful businessmen in the history of Hong Kong with streets, parks, and buildings across Hong Kong still bearing his name.

Speaking on behalf of the Armenian community of China, Henri Arslanian highlighted the symbolic importance of this event and presented Mr. and Mrs. Maxian with a real piece from Mt. Ararat in appreciation of their years of devotion to the community and to celebrate their efforts in bringing the idea of creating an Armenian center to life.

Jack Maxian, in his inauguration speech, said, “I am convinced that, very soon, with your personal and collective commitment, the capacity of the center will multiply and the Armenian community of China will become exemplary in its patriotic and Armenian-oriented activity.” Jack and Julie Maxian generously donated a large collection of paintings to adorn the walls of the center, all of which were made especially for this occasion. The guests also enjoyed a wonderful Armenian dinner prepared by Julie Maxian for the occasion.

On the second day of the great celebration, Bishop Haigazoun Najarian held the Holy Mass, the first ever celebrated in the center. The guests also enjoyed brunch, after which they attended a lecture by Prof. Sebouh Aslanian, the Chair of Armenian Studies at UCLA, who traveled to Hong Kong for the occasion and described the role of Julfan Armenian merchants in the early modern world of the Indian Ocean, and up to Manila and China.

Later, the guests learned that Armenian-language, history, and culture classes would be offered at the center via the Armenian Virtual College (AVC). Yervant Zorian, the founder of the AVC, described how the educational institute has been helping similar communities worldwide and the enthusiasm of the AVC team in working with the Armenian community of China in the coming years.

The Jack & Julie Hong Kong Armenian Center will now host Armenians from China and all over the world. It will hold events with guest speakers, hold exhibitions, invite Armenian artists to perform, but, most importantly, it will be a gathering venue for Armenians and their friends.

Armenians have been traveling to and living in China for centuries. In 1910, the Armenian Relief Society (ARS) created the Armenian Club of Shanghai as a station for refugees in Shanghai. The club evolved over the years into a social club where the community gathered and where Armenian weddings, baptisms, and events took place. In 1923, the 400-strong community of Harbin in northern China built their first church. Most of the Armenians in China left the country around 1949 following the communist takeover. The Armenian Club of Shanghai was converted to private ownership by the Communists in 1949, and the Armenian Church was destroyed as part of Mao’s Cultural Revolution in the late 1960’s. The Armenian community of China has been growing considerably over the last few years. It currently consists of approximately 500 Armenians living in the country, mainly in the cities of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Guangzhou, Shanghai, Nanjing, and Beijing.

Honorary guests included His Holiness Karekin II, Supreme Patriarch and Catholicos of All Armenians; His Grace Bishop Haigazoun Najarian, Primate of the Diocese of Australia and New Zealand; His Eminence Archbishop Aram Ateshian, Patriarchal Vicar of Constantinople; His Excellency the Armenian Ambassador to China, Armen Sargsyan; and the Honorary Consul of Armenia to Thailand, Arto Artinian.

The two-day celebration began with a ribbon-cutting ceremony followed by the blessing given by Catholicos Karekin II at the beautiful center altar built especially for religious events. “Armenian couples will marry here, and Armenian kids will be baptized in this house,” Jack Maxian said in his welcoming speech. “We will arrange Armenian meetings in this center, festivities devoted to Armenian culture, and foreigners will be surprised that the Armenian people are able to build an Armenian house outside of their own land.”

That evening, Catholicos Karekin II granted the St. Nerses Shnorhali Medal of Honor to Mr. and Mrs. Maxian for their devotion to the nation. “We are happy to see that Armenian national identity is so well preserved in a remote country like China, despite the small size of the community,” he said. His Holiness also visited the grave of Sir Paul Catchik Chater, likely the most famous Armenian in Asia, who moved to Hong Kong in 1864 from Calcutta India and became one of the most successful businessmen in the history of Hong Kong with streets, parks, and buildings across Hong Kong still bearing his name.

Speaking on behalf of the Armenian community of China, Henri Arslanian highlighted the symbolic importance of this event and presented Mr. and Mrs. Maxian with a real piece from Mt. Ararat in appreciation of their years of devotion to the community and to celebrate their efforts in bringing the idea of creating an Armenian center to life.

Jack Maxian, in his inauguration speech, said, “I am convinced that, very soon, with your personal and collective commitment, the capacity of the center will multiply and the Armenian community of China will become exemplary in its patriotic and Armenian-oriented activity.” Jack and Julie Maxian generously donated a large collection of paintings to adorn the walls of the center, all of which were made especially for this occasion. The guests also enjoyed a wonderful Armenian dinner prepared by Julie Maxian for the occasion.

On the second day of the great celebration, Bishop Haigazoun Najarian held the Holy Mass, the first ever celebrated in the center. The guests also enjoyed brunch, after which they attended a lecture by Prof. Sebouh Aslanian, the Chair of Armenian Studies at UCLA, who traveled to Hong Kong for the occasion and described the role of Julfan Armenian merchants in the early modern world of the Indian Ocean, and up to Manila and China.

Later, the guests learned that Armenian-language, history, and culture classes would be offered at the center via the Armenian Virtual College (AVC). Yervant Zorian, the founder of the AVC, described how the educational institute has been helping similar communities worldwide and the enthusiasm of the AVC team in working with the Armenian community of China in the coming years.

The Jack & Julie Hong Kong Armenian Center will now host Armenians from China and all over the world. It will hold events with guest speakers, hold exhibitions, invite Armenian artists to perform, but, most importantly, it will be a gathering venue for Armenians and their friends.

Armenians have been traveling to and living in China for centuries. In 1910, the Armenian Relief Society (ARS) created the Armenian Club of Shanghai as a station for refugees in Shanghai. The club evolved over the years into a social club where the community gathered and where Armenian weddings, baptisms, and events took place. In 1923, the 400-strong community of Harbin in northern China built their first church. Most of the Armenians in China left the country around 1949 following the communist takeover. The Armenian Club of Shanghai was converted to private ownership by the Communists in 1949, and the Armenian Church was destroyed as part of Mao’s Cultural Revolution in the late 1960’s. The Armenian community of China has been growing considerably over the last few years. It currently consists of approximately 500 Armenians living in the country, mainly in the cities of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Guangzhou, Shanghai, Nanjing, and Beijing.

Wednesday, November 13, 2013

Examining ‘the Denialist Habitus in Post-Genocidal Turkey’

An Interview with Talin Suciyan

The forced eradication of the Armenians from their homeland in 1915 has generated a unique scholarship that closely examines the genocidal policies from 1915 to 1923. One aspect, however, has remained blurred: the post-genocidal period and the repercussions of the genocide on the remaining Armenian population in Turkey. In this interview with the Armenian Weekly, Talin Suciyan shows the consistency of state policies and internalization of these policies on the level of everyday life by the larger parts of the society. According to Suciyan, the normalization of denial both by the state and the society created a denialist habitus. She also presents tangible examples of how the Armenians had to become part of the denial as there was no other way of existence for them in the public sphere.

Suciyan was born in Istanbul, Turkey. She attended the Armenian elementary school in her town and the Sahakyan Nunyan Armenian High School in Samatya. She graduated from Istanbul University’s radio, TV, and cinema department and continued her studies in Germany, South Africa, and India, receiving her master’s degree in social sciences. For 10 years, she worked in the field of journalism, producing and co-directing documentaries. From 2007-08, she reported from Armenia for Agos Weekly. In October 2008, she began to work at Ludwig Maximilian University’s (LMU) Institute of Near and Middle Eastern Studies as a teaching fellow, and as a doctoral student at the university’s Chair of Turkish studies. Currently, Suciyan teaches the history of late Ottoman Turkey, Republican Turkey, and Western Armenian. Since 2010, she has organized lecture series at LMU aimed at bridging the gap between Armenian and Ottoman studies. She successfully defended her Ph.D. dissertation in June 2013.

Varak Ketsemanian: In the introduction of your dissertation, you discuss the concept of denialist habitus. What were the mechanisms of denial in the post-genocide Republic of Turkey?

Talin Suciyan: Perhaps it would be good to start with an explanation of what I mean by “post-genocide habitus of denial.” This concept encompasses all of the officially organized policies, such as the 20 Classes, Wealth Tax, Citizen Speak Turkish Campaigns, prohibitions of professions for non-Muslims, etc., and the social support provided to these policies. These have mostly been against non-Muslims or others who for some reason became the target of state. Denialist habitus constitutes our daily life with its various forms. For instance, the Talat Pasha Elementary School, Ergenekon Avenue, and all the streets named after CUP leaders are very ordinary part of our lives. These examples become striking when you imagine having a school named after Hitler in Germany. Normalized hatred in the public sphere, in the media and press against the Kurds, Armenians, Alewites, or other non-Muslim groups are all part of this habitus. Juridical system is also not exempt from it. The cases of “denigrating Turkishness” and the atmosphere created through these cases in the society—involving the confiscation of properties of non-Muslims, kidnapping Armenians girls, systematic attacks on Armenians remaining in Asia Minor and northern Mesopotamia, changing the names of the villages where non-Muslims used to live, destroying their cultural heritage in the provinces, or using their churches or monasteries as stables—are all part of the post-genocide denialist habitus in Turkey.

With all of these practices, not only is the annihilation of these people denied, but also their very existence and history. As a result, the feeling of justice in the society could not be established. In this atmosphere, racism on a daily basis becomes ordinary. This racism, both in the provinces and in Istanbul, can easily be traced in the oral histories I’ve conducted. Through their personal histories, we see how they experienced it while playing on the streets, attending funerals, weddings, Sunday masses, or gatherings in their houses—in other words, their very existence in the provinces easily turned into a reason to be attacked. Of course, this was not only against Armenians. For instance, Jews in Tokat also had to deal with racist attacks on a daily basis. In Agop Aslanyan’s book, Adım Agop Memleketim Tokat, he refers to the racist attacks against Jews on the street, where they were equated with lice. [1]

The victims had no one, no institution to count on, they were absolutely alone in the struggle for their very existence and the denial of that existence. Their complaints were not heard. The assailants consequently knew that by attacking non-Muslims, verbally and physically, there would no punitive consequences. Official state policies during the first decades of the republican era in Turkey and also later enabled and supported the establishment and normalization of this habitus.

In other words, the republican state institutionalized this habitus of denial with its official policies both on the national and local levels, and supported its internalization on the societal level. Therefore, societal peace, a feeling of justice and freedom, cannot be established unless Turkey recognizes what happened between 1915 and 1923.

V.K.: On p. 4, you write, “Armenian Sources themselves become part of the Denial.” How?

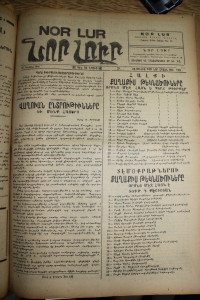

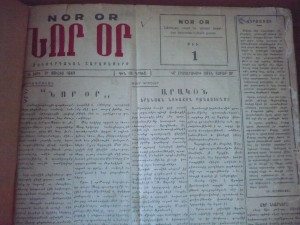

T.S.: Yes, in this habitus of denial, the Armenian press was required to write certain things in certain ways. For instance, according to the memoirs of Ara Koçunyan, the editor-in-chief of the “Aztarar” daily, Manuk Aslanyan was called by the governor Muhittin Üstündağ to his office because he failed to cover the news of the annexation of Sanjak (Hatay). Although Aslanyan published an editorial two days after this conversation, his newspaper was nevertheless closed. There are various other examples of prohibiting or closing Armenian newspapers without any reason. “Nor Or” and “Hay Gin” are just two other examples from the republican era. These newspapers were apparently not good enough in internalizing the denialist habitus.. For instance, the “Marmara” newspaper, in its reporting on the destruction of an Armenian church in Sivas in the 1940’s, put the responsibility of locum tenens on Kevork Arch. Aslanyan, although the church was dynamited by Turkish officials.

Another example could be given in the context of relations with the diaspora: Armenian intellectuals and the press in Istanbul were expected to distance themselves from diaspora communities. So, they too had to use hostile language when describing other Armenian communities in the diaspora, denying the fact that those people in other parts of the world were their relatives. This continues to be an issue even today. However, I should point out that diaspora hatred is one of the oldest and deepest components of Kemalism, which can be traced in the republican archives in Turkey. The state prepared detailed reports on the Armenian newspapers and their editors-in-chief in the 1930’s and 1940’s–and, most probably, in later periods as well. In these reports, one of the most important criteria was the relation to other communities in the diaspora. In other words, for an Armenian newspaper to be regarded as “state friendly,” the first question was whether it was reporting news from other communities or not, and whether it had a network with other communities. It was in this atmosphere that the post-genocide habitus of denial was partly internalized by some Armenian community members, public opinion makers. The book-burning ceremony undertaken by Armenian community leaders of The 40 Days of Musa Dagh can be read in this context, too. [2] It is also important to emphasize that by being part of this habitus, the editors of the newspapers were hoping to have some more bargaining power with the state on other communal issues, such as the confiscation of properties or laws regulating the communal life. We can trace this very clearly in the editorials. However, this hope never turned into a reality.

It is important to underline, that I am not blaming anyone for what they did, or what they could not do, I only point out the sword of Democles that has been hanging over their heads.

V.K.: What role did the Armenian newspapers play in the re-construction of the community’s image in post-genocide Istanbul?

T.S.: Armenian newspapers had some very difficult tasks to accomplish. In the absence of Armenian history classes and an atmosphere of absolute prohibition of all books related to Armenian history, the newspapers were trying to provide historical knowledge by publishing biographies, and series on Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, the history of Armenian Church, etc.

Secondly, they had to react to anti-Armenian campaigns in the absence of representative bodies. Turkish editors, many of whom were parliamentarians at the same time, referred to Armenian editors and journalist as the representatives of their community, although there was no notion of representation. This very political task often put their existence in danger. Armenian newspapers were translating almost all news items related to Armenians from Turkish newspapers, and they were following the Armenian press in other countries. Thus, reading Armenian newspapers meant both following the agenda of Turkey and partly the agenda of Armenians in other parts of the world. Furthermore, Armenian newspapers were following the court cases opened against the pious foundations that mostly ended up with confiscated properties, such as in the case of Sanasaryan Han, Yusufyan Han, the cemetery of Pangalti, and many others. Cases of “denigrating Turkishness,” which have been filed almost exclusively against non-Muslims, were also followed closely. One can also find information about Armenian life in the provinces in the papers. Important primary sources, such as official documents, decisions of the Patriarchate or Catholicosates were all published in the newspapers. I should add that there were tens of newspapers and journals in the first decades of the republic, and that they all had different priorities. Therefore, Armenian newspapers and yearbooks are very good sources of republican history, like the memoirs of the patriarchs and public intellectuals, minutes and reports of the General (Armenian) National Assembly, the letters of the Catholicoses, among others.

V.K.: What were the repercussions of this denialist habitus? What was its social, political, cultural, and economic impact on the writing of the history of the community?

T.S.: We cannot talk about a historiography on Armenians during the republican years. Non-Muslims only appear in historical research when it concerns attacks, such as the pogroms of Sept. 6-7 1955, the Wealth Tax, 20 Classes, and others. Of course, the literature in these fields helps us a lot, but these are peak moments. One should look at the practices of daily life to understand how these tax policies, pogroms, or organized attacks affected them. How did the circumstances enable these attacks or policies against which there was no opposition? The denialist habitus as a concept helps us understand everyday life, which kept the society ready for provocations and reproductions of racism. I should perhaps add that republican elite, from 1923 onwards, was trying to “solve the problem” of the non-Muslims remaining in the country. In the memoirs of Patriarch Zaven Der Yeghiayan, we can see the process of negotiations with Refet Pasha [Bele] on this issue. This was also discussed during the deliberations prior to the signing of the Lausanne Treaty. In the minutes of secret parliament hearings we read how the presence of non-Muslims has been problematized. [3] Consequently, through the absolute prohibition of opening Armenian schools, the kidnapping Armenian girls throughout the republican period, the raiding of homes, the dynamiting or confiscation of cultural monuments, republican governments wanted to push the remaining Armenians out of Asia Minor and northern Mesopotamia, while at the same time, imagining Istanbul as a panopticon, a strict zone of control where all non-Muslims should be concentrated. A similar policy was implemented on the island of Imroz, where Greeks were allowed to remain after 1923. First, in the 1960s, an open-air prison was established there: criminals were brought to the island with their families. Consequently, the crime rate increased considerably. Then, Muslim settlers from the Black Sea region were brought to the island. Constant demographic engineering attempts were made in order to push the remaining Greeks out of the island. The consequences of these policies were disastrous. Both in Imroz and in the provinces republican governments pursued the same aim: Creating a society without non-Muslims, breaking the link between the people and the geography they lived in, and in the long run, eradicating the memory of their existence.

V.K.: How did the first post-genocide generation of intellectuals reflect on the image of the Armenian community of Istanbul in the 1930’s and 1940’s?

T.S.: It is difficult to talk about one image. However, there was one very important characteristic about the “Nor Or” generation: They were the first generation of intellectuals who were born right after 1915 and were mostly active in leftist politics in Turkey. Why did they feel the need to publish an Armenian language newspaper? I think this is an important question to ask. It is quite clear that they had no other place to bring up the issues that were related to the community. They were urging for a more democratic community administration, with more participation and, on the other hand, they were very expressive about the anti-Armenian state policies and anti-Armenian campaigns reproduced by the public opinion-makers. Avedis Aliksanyan, Aram Pehlivanyan, Zaven Biberyan, Vartan and Jak Ihmalyan brothers, and others were pointing out the changing conjuncture after World War II and the need for equality for non-Muslims, in particular for Armenians in Turkey. “Nor Or” was one of the most outspoken and courageous newspapers in the republican history of Turkey. For instance, Zaven Biberyan advocated the right to immigrate to Soviet Armenia for Armenians in Turkey, which was quite dangerous; or he drew parallels between Jews and Armenians while responding to the anti-Armenian campaigns in the Turkish press. Most likely, these were the reasons behind the prohibition of “Nor Or” in December 1946, by Martial Law. Although there were other newspapers that were banned for a certain period, “Nor Or” was the only Armenian newspaper that was prohibited for good. The editors were imprisoned, and later left the country. Zaven Biberyan returned in the mid-1950’s, but all the others lost their contact with the society they were born and raised in.

V.K.: In your dissertation, you write that “Another international crisis parallel to the issue of Patriarchal election crisis was the territorial claim of the Armenian political organizations at the San Francisco Conference. This claim was pushed further by the USSR government.” How did Turkey deal with the territorial claims presented by the Armenian political organizations?

T.S.: This was one of the most challenging issues for the Armenian community in Turkey. Turkey had sent a group of editors to San Francisco, and they remained there for quite long, around three months. Their task was to lobby for Turkey. The territorial claims presented by the Armenian organizations in the San Francisco Conference had a shocking impact on the Turkish delegation, especially when this claim was coupled with the call for immigration to Soviet Armenia by Stalin. With the call for immigration to Soviet Armenia, it was quite easy to blame all Armenians for being communists, especially the ones in Turkey, since they were queued in front of the USSR Embassy in Istanbul to register for immigration. At the end, Armenians from Turkey only waved to the ships passing through the Bosporus, and none of them were able to go to Soviet Armenia in 1946. The reason is not yet clear to me, there was always a question mark in the minds of Soviet officials regarding the Armenians in Turkey. After World War II, hatred against communism in Turkey was heightened to a great extent as a result of the territorial claims and immigration call for Armenians.

The anti-Armenian campaign in Turkey was launched by the editors who reported from San Francisco. The newspapers “Yeni Sabah,” [4] “Gece Postası,” [5] “Vatan,” [6] “Cumhuriyet,” [7] “Akşam,” [8] “Tasvir,” [9] the abovementioned daily from Adana, “Keloğlan,” [10] “Son Telgraf,” [11] and “Tanin” all used quite a bit of racist language against Armenians. Asım Us, for instance, in his editorial for “Vakıt” asked Armenian intellectuals “to be conscientious and fulfill their duties.” [12] However, this was not typical to that period only. Throughout the year, after the San Francisco numerous conference articles were published along the same lines. In September 1945, Peyami Safa called the Armenians of Turkey to duty with an article entitled, “Armenians of Turkey, where are you?” published in “Tasvir” in September 1945. [13] The editors of the Armenian newspapers tried to respond to all these attacks. Aram Pehlivanyan, who penned a Turkish editorial published in “Nor Or,” in order to be heard by Turkish public opinion makers, thus explained the situation: “We are witnessing attacks of some of the Turkish newspapers against Armenians. The Armenian press is trying to respond to these attacks as much as it can. However, we have to admit that Armenian newspapers can have only a little impact on Turkish public opinion. Therefore, this self-defense is as ridiculous as fighting with a pin as opposed to a sword.” [14]

V.K.: How did the Patriarchal Election Crisis of 1944-1950 discuss the changing power relations on the post-World War II international scene?

T.S.: With the sudden death of Patriarch Mesrob Naroyan in 1944, Kevork Arch. Arslanyan was appointed as locum tenens. First, this was the period when a conflict turned into a court case between Arch. Arslanyan and the Armenian Hospital Sourp Prgich over the inheritance of Patriarch Naroyan. Second, the Turkish government was hindering the gatherings of the General (Armenian) National Assembly (GNA) and this was paralyzing the whole community administration, for the patriarchal elections could only take place with the GNA meeting. This had already been a problem starting in the 1930’s, when the whole community administration, (i.e., Nizamname of Armenian millet) had started to be undermined systematically. Kemalist secularism of the new Turkish state had targeted the administrations of non-Muslim communities, since they had the right to administer their communities based on Nizamnames, and the republican state had nothing to offer instead of these communal rights. In the last analysis, this policy was enabling the state to create de facto regulations according to its own will and interest. Coming back to the topic of patriarchal elections, not being able to organize the elections resulted in a split in the community: those who were for and those who were against Arch. Arslanyan. Almost every week, attacks and quarrels between the two groups took place in various churches.

Thirdly, the Catholicosate of Etchmiadzin, which was becoming active in the diaspora with Stalin’s immigration call, was also involved in this crisis, as well as the Catholicosate of Cilicia in Antelias, Lebanon, and other communities in the diaspora. This was the first communal crisis that turned into an international one during the republican years, leaving the Armenian community in Turkey in a very fragile position, since there were no mechanisms of representation and no real mechanisms of solving the problem. In other words, this crisis was a result of the eradication of the community’s legal basis, which had continued after 1915 and taken a systematic character with the republican policies. If the Ottoman state until 1915 had some kind of responsibility towards its non-Muslim millets, citizens or subjects, there was a complete evaporation of this responsibility during the republican period. Communities were told to no longer be communities, but equal citizens of the republic, like any other citizen of Turkey, which in reality did not apply and, more importantly, meant that Armenians no longer had the rights stemming from Nizamname. Thus, the legal basis of the communities, gained during the 19th century, was first problematized by the republican governments and then systematically eradicated, leaving the communities alone with the problems created as a result of this eradication.

Armenian newspapers, public opinion-makers, and the reports prepared by the GNA, eventually gathered by December 1950, are very rich sources to understand this very problematic period. The following comment was made in the report prepared by the investigative committee:

“This is not a history of a period, since it does not include all the incidents with their reasons and results. This is not a biographical account of someone. This is only 1 page of the overall crisis that our community has been going through for the last 30 years.” [15]

Last but not least, it is important to emphasize that this is not only the history of the Armenian community, but the history of Turkey during the first decades of the republican period. Single-party years and also decades that followed should be re-read in light of these sources, which would eventually radically change the historiography.

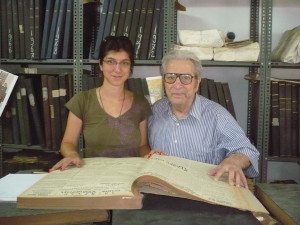

V.K.: Why did you dedicate your dissertation to the memory of Varujan Köseyan?

T.S.: Most of the Armenian newspapers that I referenced in my dissertation (“Nor Lur,” “Aysor,” “Tebi Luys,” “Marmara,” “Ngar,” “Panper,” and others) were located in the archives of the Sourp Prgich Armenian Hospital in Istanbul. This archive was put together by the late Varujan Köseyan (1920-2011), who rescued hundreds of volumes of Armenian newspapers from recycling. I spent quite a bit of time with him during the last two years of his life conducting interviews, and I was honored to enjoy his friendship. The room that I was working in, was like a storage room. Thanks to the efforts of the hospital administration, especially of Arsen Yarman and Zakarya Mildanoğlu, the archive room has been recently renovated and is now waiting for its researchers. Unfortunately, Köseyan could not see it. Yet, without his efforts, this research could not have been done by using such a wide range of sources, nor could the archive have been established. We owe our history to Köseyan.

The forced eradication of the Armenians from their homeland in 1915 has generated a unique scholarship that closely examines the genocidal policies from 1915 to 1923. One aspect, however, has remained blurred: the post-genocidal period and the repercussions of the genocide on the remaining Armenian population in Turkey. In this interview with the Armenian Weekly, Talin Suciyan shows the consistency of state policies and internalization of these policies on the level of everyday life by the larger parts of the society. According to Suciyan, the normalization of denial both by the state and the society created a denialist habitus. She also presents tangible examples of how the Armenians had to become part of the denial as there was no other way of existence for them in the public sphere.

Suciyan was born in Istanbul, Turkey. She attended the Armenian elementary school in her town and the Sahakyan Nunyan Armenian High School in Samatya. She graduated from Istanbul University’s radio, TV, and cinema department and continued her studies in Germany, South Africa, and India, receiving her master’s degree in social sciences. For 10 years, she worked in the field of journalism, producing and co-directing documentaries. From 2007-08, she reported from Armenia for Agos Weekly. In October 2008, she began to work at Ludwig Maximilian University’s (LMU) Institute of Near and Middle Eastern Studies as a teaching fellow, and as a doctoral student at the university’s Chair of Turkish studies. Currently, Suciyan teaches the history of late Ottoman Turkey, Republican Turkey, and Western Armenian. Since 2010, she has organized lecture series at LMU aimed at bridging the gap between Armenian and Ottoman studies. She successfully defended her Ph.D. dissertation in June 2013.

Varak Ketsemanian: In the introduction of your dissertation, you discuss the concept of denialist habitus. What were the mechanisms of denial in the post-genocide Republic of Turkey?

Talin Suciyan: Perhaps it would be good to start with an explanation of what I mean by “post-genocide habitus of denial.” This concept encompasses all of the officially organized policies, such as the 20 Classes, Wealth Tax, Citizen Speak Turkish Campaigns, prohibitions of professions for non-Muslims, etc., and the social support provided to these policies. These have mostly been against non-Muslims or others who for some reason became the target of state. Denialist habitus constitutes our daily life with its various forms. For instance, the Talat Pasha Elementary School, Ergenekon Avenue, and all the streets named after CUP leaders are very ordinary part of our lives. These examples become striking when you imagine having a school named after Hitler in Germany. Normalized hatred in the public sphere, in the media and press against the Kurds, Armenians, Alewites, or other non-Muslim groups are all part of this habitus. Juridical system is also not exempt from it. The cases of “denigrating Turkishness” and the atmosphere created through these cases in the society—involving the confiscation of properties of non-Muslims, kidnapping Armenians girls, systematic attacks on Armenians remaining in Asia Minor and northern Mesopotamia, changing the names of the villages where non-Muslims used to live, destroying their cultural heritage in the provinces, or using their churches or monasteries as stables—are all part of the post-genocide denialist habitus in Turkey.

With all of these practices, not only is the annihilation of these people denied, but also their very existence and history. As a result, the feeling of justice in the society could not be established. In this atmosphere, racism on a daily basis becomes ordinary. This racism, both in the provinces and in Istanbul, can easily be traced in the oral histories I’ve conducted. Through their personal histories, we see how they experienced it while playing on the streets, attending funerals, weddings, Sunday masses, or gatherings in their houses—in other words, their very existence in the provinces easily turned into a reason to be attacked. Of course, this was not only against Armenians. For instance, Jews in Tokat also had to deal with racist attacks on a daily basis. In Agop Aslanyan’s book, Adım Agop Memleketim Tokat, he refers to the racist attacks against Jews on the street, where they were equated with lice. [1]

The victims had no one, no institution to count on, they were absolutely alone in the struggle for their very existence and the denial of that existence. Their complaints were not heard. The assailants consequently knew that by attacking non-Muslims, verbally and physically, there would no punitive consequences. Official state policies during the first decades of the republican era in Turkey and also later enabled and supported the establishment and normalization of this habitus.

In other words, the republican state institutionalized this habitus of denial with its official policies both on the national and local levels, and supported its internalization on the societal level. Therefore, societal peace, a feeling of justice and freedom, cannot be established unless Turkey recognizes what happened between 1915 and 1923.

V.K.: On p. 4, you write, “Armenian Sources themselves become part of the Denial.” How?

T.S.: Yes, in this habitus of denial, the Armenian press was required to write certain things in certain ways. For instance, according to the memoirs of Ara Koçunyan, the editor-in-chief of the “Aztarar” daily, Manuk Aslanyan was called by the governor Muhittin Üstündağ to his office because he failed to cover the news of the annexation of Sanjak (Hatay). Although Aslanyan published an editorial two days after this conversation, his newspaper was nevertheless closed. There are various other examples of prohibiting or closing Armenian newspapers without any reason. “Nor Or” and “Hay Gin” are just two other examples from the republican era. These newspapers were apparently not good enough in internalizing the denialist habitus.. For instance, the “Marmara” newspaper, in its reporting on the destruction of an Armenian church in Sivas in the 1940’s, put the responsibility of locum tenens on Kevork Arch. Aslanyan, although the church was dynamited by Turkish officials.

Another example could be given in the context of relations with the diaspora: Armenian intellectuals and the press in Istanbul were expected to distance themselves from diaspora communities. So, they too had to use hostile language when describing other Armenian communities in the diaspora, denying the fact that those people in other parts of the world were their relatives. This continues to be an issue even today. However, I should point out that diaspora hatred is one of the oldest and deepest components of Kemalism, which can be traced in the republican archives in Turkey. The state prepared detailed reports on the Armenian newspapers and their editors-in-chief in the 1930’s and 1940’s–and, most probably, in later periods as well. In these reports, one of the most important criteria was the relation to other communities in the diaspora. In other words, for an Armenian newspaper to be regarded as “state friendly,” the first question was whether it was reporting news from other communities or not, and whether it had a network with other communities. It was in this atmosphere that the post-genocide habitus of denial was partly internalized by some Armenian community members, public opinion makers. The book-burning ceremony undertaken by Armenian community leaders of The 40 Days of Musa Dagh can be read in this context, too. [2] It is also important to emphasize that by being part of this habitus, the editors of the newspapers were hoping to have some more bargaining power with the state on other communal issues, such as the confiscation of properties or laws regulating the communal life. We can trace this very clearly in the editorials. However, this hope never turned into a reality.

It is important to underline, that I am not blaming anyone for what they did, or what they could not do, I only point out the sword of Democles that has been hanging over their heads.

V.K.: What role did the Armenian newspapers play in the re-construction of the community’s image in post-genocide Istanbul?

T.S.: Armenian newspapers had some very difficult tasks to accomplish. In the absence of Armenian history classes and an atmosphere of absolute prohibition of all books related to Armenian history, the newspapers were trying to provide historical knowledge by publishing biographies, and series on Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, the history of Armenian Church, etc.

Secondly, they had to react to anti-Armenian campaigns in the absence of representative bodies. Turkish editors, many of whom were parliamentarians at the same time, referred to Armenian editors and journalist as the representatives of their community, although there was no notion of representation. This very political task often put their existence in danger. Armenian newspapers were translating almost all news items related to Armenians from Turkish newspapers, and they were following the Armenian press in other countries. Thus, reading Armenian newspapers meant both following the agenda of Turkey and partly the agenda of Armenians in other parts of the world. Furthermore, Armenian newspapers were following the court cases opened against the pious foundations that mostly ended up with confiscated properties, such as in the case of Sanasaryan Han, Yusufyan Han, the cemetery of Pangalti, and many others. Cases of “denigrating Turkishness,” which have been filed almost exclusively against non-Muslims, were also followed closely. One can also find information about Armenian life in the provinces in the papers. Important primary sources, such as official documents, decisions of the Patriarchate or Catholicosates were all published in the newspapers. I should add that there were tens of newspapers and journals in the first decades of the republic, and that they all had different priorities. Therefore, Armenian newspapers and yearbooks are very good sources of republican history, like the memoirs of the patriarchs and public intellectuals, minutes and reports of the General (Armenian) National Assembly, the letters of the Catholicoses, among others.

V.K.: What were the repercussions of this denialist habitus? What was its social, political, cultural, and economic impact on the writing of the history of the community?

T.S.: We cannot talk about a historiography on Armenians during the republican years. Non-Muslims only appear in historical research when it concerns attacks, such as the pogroms of Sept. 6-7 1955, the Wealth Tax, 20 Classes, and others. Of course, the literature in these fields helps us a lot, but these are peak moments. One should look at the practices of daily life to understand how these tax policies, pogroms, or organized attacks affected them. How did the circumstances enable these attacks or policies against which there was no opposition? The denialist habitus as a concept helps us understand everyday life, which kept the society ready for provocations and reproductions of racism. I should perhaps add that republican elite, from 1923 onwards, was trying to “solve the problem” of the non-Muslims remaining in the country. In the memoirs of Patriarch Zaven Der Yeghiayan, we can see the process of negotiations with Refet Pasha [Bele] on this issue. This was also discussed during the deliberations prior to the signing of the Lausanne Treaty. In the minutes of secret parliament hearings we read how the presence of non-Muslims has been problematized. [3] Consequently, through the absolute prohibition of opening Armenian schools, the kidnapping Armenian girls throughout the republican period, the raiding of homes, the dynamiting or confiscation of cultural monuments, republican governments wanted to push the remaining Armenians out of Asia Minor and northern Mesopotamia, while at the same time, imagining Istanbul as a panopticon, a strict zone of control where all non-Muslims should be concentrated. A similar policy was implemented on the island of Imroz, where Greeks were allowed to remain after 1923. First, in the 1960s, an open-air prison was established there: criminals were brought to the island with their families. Consequently, the crime rate increased considerably. Then, Muslim settlers from the Black Sea region were brought to the island. Constant demographic engineering attempts were made in order to push the remaining Greeks out of the island. The consequences of these policies were disastrous. Both in Imroz and in the provinces republican governments pursued the same aim: Creating a society without non-Muslims, breaking the link between the people and the geography they lived in, and in the long run, eradicating the memory of their existence.

V.K.: How did the first post-genocide generation of intellectuals reflect on the image of the Armenian community of Istanbul in the 1930’s and 1940’s?

T.S.: It is difficult to talk about one image. However, there was one very important characteristic about the “Nor Or” generation: They were the first generation of intellectuals who were born right after 1915 and were mostly active in leftist politics in Turkey. Why did they feel the need to publish an Armenian language newspaper? I think this is an important question to ask. It is quite clear that they had no other place to bring up the issues that were related to the community. They were urging for a more democratic community administration, with more participation and, on the other hand, they were very expressive about the anti-Armenian state policies and anti-Armenian campaigns reproduced by the public opinion-makers. Avedis Aliksanyan, Aram Pehlivanyan, Zaven Biberyan, Vartan and Jak Ihmalyan brothers, and others were pointing out the changing conjuncture after World War II and the need for equality for non-Muslims, in particular for Armenians in Turkey. “Nor Or” was one of the most outspoken and courageous newspapers in the republican history of Turkey. For instance, Zaven Biberyan advocated the right to immigrate to Soviet Armenia for Armenians in Turkey, which was quite dangerous; or he drew parallels between Jews and Armenians while responding to the anti-Armenian campaigns in the Turkish press. Most likely, these were the reasons behind the prohibition of “Nor Or” in December 1946, by Martial Law. Although there were other newspapers that were banned for a certain period, “Nor Or” was the only Armenian newspaper that was prohibited for good. The editors were imprisoned, and later left the country. Zaven Biberyan returned in the mid-1950’s, but all the others lost their contact with the society they were born and raised in.

V.K.: In your dissertation, you write that “Another international crisis parallel to the issue of Patriarchal election crisis was the territorial claim of the Armenian political organizations at the San Francisco Conference. This claim was pushed further by the USSR government.” How did Turkey deal with the territorial claims presented by the Armenian political organizations?

T.S.: This was one of the most challenging issues for the Armenian community in Turkey. Turkey had sent a group of editors to San Francisco, and they remained there for quite long, around three months. Their task was to lobby for Turkey. The territorial claims presented by the Armenian organizations in the San Francisco Conference had a shocking impact on the Turkish delegation, especially when this claim was coupled with the call for immigration to Soviet Armenia by Stalin. With the call for immigration to Soviet Armenia, it was quite easy to blame all Armenians for being communists, especially the ones in Turkey, since they were queued in front of the USSR Embassy in Istanbul to register for immigration. At the end, Armenians from Turkey only waved to the ships passing through the Bosporus, and none of them were able to go to Soviet Armenia in 1946. The reason is not yet clear to me, there was always a question mark in the minds of Soviet officials regarding the Armenians in Turkey. After World War II, hatred against communism in Turkey was heightened to a great extent as a result of the territorial claims and immigration call for Armenians.

The anti-Armenian campaign in Turkey was launched by the editors who reported from San Francisco. The newspapers “Yeni Sabah,” [4] “Gece Postası,” [5] “Vatan,” [6] “Cumhuriyet,” [7] “Akşam,” [8] “Tasvir,” [9] the abovementioned daily from Adana, “Keloğlan,” [10] “Son Telgraf,” [11] and “Tanin” all used quite a bit of racist language against Armenians. Asım Us, for instance, in his editorial for “Vakıt” asked Armenian intellectuals “to be conscientious and fulfill their duties.” [12] However, this was not typical to that period only. Throughout the year, after the San Francisco numerous conference articles were published along the same lines. In September 1945, Peyami Safa called the Armenians of Turkey to duty with an article entitled, “Armenians of Turkey, where are you?” published in “Tasvir” in September 1945. [13] The editors of the Armenian newspapers tried to respond to all these attacks. Aram Pehlivanyan, who penned a Turkish editorial published in “Nor Or,” in order to be heard by Turkish public opinion makers, thus explained the situation: “We are witnessing attacks of some of the Turkish newspapers against Armenians. The Armenian press is trying to respond to these attacks as much as it can. However, we have to admit that Armenian newspapers can have only a little impact on Turkish public opinion. Therefore, this self-defense is as ridiculous as fighting with a pin as opposed to a sword.” [14]

V.K.: How did the Patriarchal Election Crisis of 1944-1950 discuss the changing power relations on the post-World War II international scene?

T.S.: With the sudden death of Patriarch Mesrob Naroyan in 1944, Kevork Arch. Arslanyan was appointed as locum tenens. First, this was the period when a conflict turned into a court case between Arch. Arslanyan and the Armenian Hospital Sourp Prgich over the inheritance of Patriarch Naroyan. Second, the Turkish government was hindering the gatherings of the General (Armenian) National Assembly (GNA) and this was paralyzing the whole community administration, for the patriarchal elections could only take place with the GNA meeting. This had already been a problem starting in the 1930’s, when the whole community administration, (i.e., Nizamname of Armenian millet) had started to be undermined systematically. Kemalist secularism of the new Turkish state had targeted the administrations of non-Muslim communities, since they had the right to administer their communities based on Nizamnames, and the republican state had nothing to offer instead of these communal rights. In the last analysis, this policy was enabling the state to create de facto regulations according to its own will and interest. Coming back to the topic of patriarchal elections, not being able to organize the elections resulted in a split in the community: those who were for and those who were against Arch. Arslanyan. Almost every week, attacks and quarrels between the two groups took place in various churches.

Thirdly, the Catholicosate of Etchmiadzin, which was becoming active in the diaspora with Stalin’s immigration call, was also involved in this crisis, as well as the Catholicosate of Cilicia in Antelias, Lebanon, and other communities in the diaspora. This was the first communal crisis that turned into an international one during the republican years, leaving the Armenian community in Turkey in a very fragile position, since there were no mechanisms of representation and no real mechanisms of solving the problem. In other words, this crisis was a result of the eradication of the community’s legal basis, which had continued after 1915 and taken a systematic character with the republican policies. If the Ottoman state until 1915 had some kind of responsibility towards its non-Muslim millets, citizens or subjects, there was a complete evaporation of this responsibility during the republican period. Communities were told to no longer be communities, but equal citizens of the republic, like any other citizen of Turkey, which in reality did not apply and, more importantly, meant that Armenians no longer had the rights stemming from Nizamname. Thus, the legal basis of the communities, gained during the 19th century, was first problematized by the republican governments and then systematically eradicated, leaving the communities alone with the problems created as a result of this eradication.

Armenian newspapers, public opinion-makers, and the reports prepared by the GNA, eventually gathered by December 1950, are very rich sources to understand this very problematic period. The following comment was made in the report prepared by the investigative committee:

“This is not a history of a period, since it does not include all the incidents with their reasons and results. This is not a biographical account of someone. This is only 1 page of the overall crisis that our community has been going through for the last 30 years.” [15]

Last but not least, it is important to emphasize that this is not only the history of the Armenian community, but the history of Turkey during the first decades of the republican period. Single-party years and also decades that followed should be re-read in light of these sources, which would eventually radically change the historiography.

V.K.: Why did you dedicate your dissertation to the memory of Varujan Köseyan?

T.S.: Most of the Armenian newspapers that I referenced in my dissertation (“Nor Lur,” “Aysor,” “Tebi Luys,” “Marmara,” “Ngar,” “Panper,” and others) were located in the archives of the Sourp Prgich Armenian Hospital in Istanbul. This archive was put together by the late Varujan Köseyan (1920-2011), who rescued hundreds of volumes of Armenian newspapers from recycling. I spent quite a bit of time with him during the last two years of his life conducting interviews, and I was honored to enjoy his friendship. The room that I was working in, was like a storage room. Thanks to the efforts of the hospital administration, especially of Arsen Yarman and Zakarya Mildanoğlu, the archive room has been recently renovated and is now waiting for its researchers. Unfortunately, Köseyan could not see it. Yet, without his efforts, this research could not have been done by using such a wide range of sources, nor could the archive have been established. We owe our history to Köseyan.

Sunday, November 10, 2013

2003 Nobel Prize for MRI Denied to Raymond Vahan Damadian

By George B. Kauffman

According to the late Ulf Lagerkvist, a member of the Swedish Academy of Sciences who participated in judging nominations for the Chemistry Prize, “It is in the nature of the Nobel Prize that there will always be a number of candidates who obviously deserve to be rewarded but never get the accolade.” Usually, a losing candidate merely accepts the injustice. But in the case of the 2003 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine of $1.3 million, awarded 10 years ago to University of Illinois Chemist Paul C. Lauterbur (1929-2007) and University of Nottingham (UK) Physicist Sir Peter Mansfield (b. 1933) “for their discoveries concerning magnetic resonance imaging,” the undoubtedly deserving candidate, Raymond Vahan Damadian, M.D. (b. 1936), an American of Armenian descent, did not take this injustice lying down.

A group called “The Friends of Raymond Damadian” protested the denial with full-page advertisements, “The Shameful Wrong That Must Be Righted” in the New York Times, Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, and Stockholm’s Dagens Nyheter. His exclusion scandalized the scientific community, in general, and the Armenian community, in particular. Damadian correctly claimed that he had invented the MRI and that Lauterbur and Mansfield had merely refined the technology. On Sept. 2, 1971, Lauterbur had acknowledged that he had been inspired by Damadian’s earlier work.

Because Damadian was not included in the award, even though the Nobel statutes permit the award to be made to as many as three living individuals, his omission was clearly deliberate. The possible purported reasons for his rejection have included the fact that he was a physician not an academic scientist; his intensive lobbying for the prize; his supposedly abrasive personality; and his active support of creationism. None of these constitute valid grounds for the denial.

The careful wording of the prize citation reflects the fact that the Nobel laureates did not come up with the idea of applying nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (the term was later changed to avoid the public’s fear of the word “nuclear,” even though nuclear energy is not involved in the procedure) to medical imaging. Today magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is universally used to image every part of the body and is particularly useful in diagnosing cancer, strokes, brain tumors, multiple sclerosis, torn ligaments, and tendonitis, to name just a few conditions. An MRI scan is the best way to see inside the human body without cutting it open.

The original idea of applying NMR to medical imaging (MRI) was first proposed by Damadian, a physician, scientist, and an assistant professor of medicine and biophysics at the Downstate Medical Center State University of New York in Brooklyn. Growing up in Forest Hills, N.Y., he attended the Julliard School and became a proficient violinist. When he was still a boy, he lost his grandmother to a slow death by cancer. He vowed to find a way to detect this dreaded disease in its early, still treatable stages.

MRI scanners make use of the fact that body tissue contains lots of water (H2O), and hence protons (1H nuclei), which will be aligned in a large magnetic field. Each water molecule contains two protons. When a person is inside the scanner’s powerful magnetic field, the average magnetic moment of many protons becomes aligned with the direction of the field. A radio frequency current is briefly turned on, producing a varying electromagnetic field. This electromagnetic field has just the right frequency, known as the resonance frequency, to be absorbed and flip the spin of the protons in the magnetic field. After the electromagnetic field is turned off, the spins of the protons return to thermodynamic equilibrium and the bulk magnetization becomes realigned with the static magnetic field. During this relaxation, a radio frequency signal (electromagnetic radiation in the RF range) is generated, which can be measured with receiver coils.

Information about the origin of the signal in three-dimensional space can be obtained by applying additional magnetic fields during the scan. These additional magnetic fields can be used to generate detectable signals only from specific locations in the body (spatial excitation) and/or to make magnetization at different spatial locations precess at different frequencies, which enables http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/K-space_(MRI) encoding of spatial information. The 3D images obtained in MRI can be rotated along arbitrary orientations and manipulated by the doctor to be better able to detect tiny changes of structures within the body. These fields, generated by passing electric currents through gradient coils, make the magnetic field strength vary depending on the position within the magnet. Protons in different tissues return to their equilibrium state at different relaxation rates.

Using a primitive NMR machine, Damadian found that there was a lag in T1 and T2 relaxation times between the electrons of normal and malignant tissues, allowing him to distinguish between normal and cancerous tissue in rats implanted with tumors. In 1971, he published the seminal article for NMR use in organ imaging in the journal Science (“Tumor Detection by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance,” March 19, 1971, vol. 171, pp. 1151-1153). Nevertheless, many individuals in the scientific and NMR community considered his ideas far-fetched, and he had few supporters at this time.

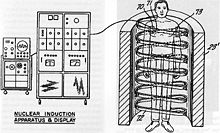

However, Damadian received a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in 1971 to continue his work. He proposed to use whole body scanning by NMR for medical diagnosis in a patent application, “Apparatus and Method for Detecting Cancer in Tissue,” filed on March 17, 1972 (U.S. Patent No. 3789832, issued Feb. 5, 1974). By February 1976, he was able to scan the interior of a live mouse using his FONAR (field focused nuclear magnetic resonance) method.

In 1977, using his machine christened “Indomitable,” now preserved in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., Damadian tried to scan himself, but the test failed because of his excessive weight. On July 3, 1977, he obtained the first human NMR image—a cross-section of his slender postgraduate assistant Larry Minkoff’s chest, which revealed heart, lungs, vertebræ, and musculature. Minkoff had to be moved over 60 positions with 20-30 signals taken from each position. Congratulatory telegrams poured in from all over the world, including one from Mansfield.

In early 1978, Damadian established the FONAR Corporation in Melville, N.Y., to produce MRI scanners. Later that year he completed his design of the first practical permanent magnet for an MRI scanner, christened “Jonah.” By 1980 his QED 80, the first commercial MRI scanner, was completed.

The MRI imaging industry expanded rapidly with more than a dozen different manufacturers. On Oct. 6, 1997, the Rehnquist U.S. Supreme Court awarded him $128,705,766 from the General Electric Company for infringement of his patent.

Damadian is universally recognized as the originator of the MRI (by President Ronald Reagan, among others) and has received numerous prestigious awards such as the National Medal of Technology in 1988, the same year he was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. He was named Knights of Vartan 2003 “Man of the Year,” and on March 18, 2004, he received the Bower Award from the Franklin Institute of Philadelphia for his development of the MRI.

George B. Kauffman is Professor Emeritus of Chemistry at California State University, Fresno, Calif.

According to the late Ulf Lagerkvist, a member of the Swedish Academy of Sciences who participated in judging nominations for the Chemistry Prize, “It is in the nature of the Nobel Prize that there will always be a number of candidates who obviously deserve to be rewarded but never get the accolade.” Usually, a losing candidate merely accepts the injustice. But in the case of the 2003 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine of $1.3 million, awarded 10 years ago to University of Illinois Chemist Paul C. Lauterbur (1929-2007) and University of Nottingham (UK) Physicist Sir Peter Mansfield (b. 1933) “for their discoveries concerning magnetic resonance imaging,” the undoubtedly deserving candidate, Raymond Vahan Damadian, M.D. (b. 1936), an American of Armenian descent, did not take this injustice lying down.

A group called “The Friends of Raymond Damadian” protested the denial with full-page advertisements, “The Shameful Wrong That Must Be Righted” in the New York Times, Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, and Stockholm’s Dagens Nyheter. His exclusion scandalized the scientific community, in general, and the Armenian community, in particular. Damadian correctly claimed that he had invented the MRI and that Lauterbur and Mansfield had merely refined the technology. On Sept. 2, 1971, Lauterbur had acknowledged that he had been inspired by Damadian’s earlier work.

Because Damadian was not included in the award, even though the Nobel statutes permit the award to be made to as many as three living individuals, his omission was clearly deliberate. The possible purported reasons for his rejection have included the fact that he was a physician not an academic scientist; his intensive lobbying for the prize; his supposedly abrasive personality; and his active support of creationism. None of these constitute valid grounds for the denial.

The careful wording of the prize citation reflects the fact that the Nobel laureates did not come up with the idea of applying nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (the term was later changed to avoid the public’s fear of the word “nuclear,” even though nuclear energy is not involved in the procedure) to medical imaging. Today magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is universally used to image every part of the body and is particularly useful in diagnosing cancer, strokes, brain tumors, multiple sclerosis, torn ligaments, and tendonitis, to name just a few conditions. An MRI scan is the best way to see inside the human body without cutting it open.

The original idea of applying NMR to medical imaging (MRI) was first proposed by Damadian, a physician, scientist, and an assistant professor of medicine and biophysics at the Downstate Medical Center State University of New York in Brooklyn. Growing up in Forest Hills, N.Y., he attended the Julliard School and became a proficient violinist. When he was still a boy, he lost his grandmother to a slow death by cancer. He vowed to find a way to detect this dreaded disease in its early, still treatable stages.

MRI scanners make use of the fact that body tissue contains lots of water (H2O), and hence protons (1H nuclei), which will be aligned in a large magnetic field. Each water molecule contains two protons. When a person is inside the scanner’s powerful magnetic field, the average magnetic moment of many protons becomes aligned with the direction of the field. A radio frequency current is briefly turned on, producing a varying electromagnetic field. This electromagnetic field has just the right frequency, known as the resonance frequency, to be absorbed and flip the spin of the protons in the magnetic field. After the electromagnetic field is turned off, the spins of the protons return to thermodynamic equilibrium and the bulk magnetization becomes realigned with the static magnetic field. During this relaxation, a radio frequency signal (electromagnetic radiation in the RF range) is generated, which can be measured with receiver coils.

Information about the origin of the signal in three-dimensional space can be obtained by applying additional magnetic fields during the scan. These additional magnetic fields can be used to generate detectable signals only from specific locations in the body (spatial excitation) and/or to make magnetization at different spatial locations precess at different frequencies, which enables http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/K-space_(MRI) encoding of spatial information. The 3D images obtained in MRI can be rotated along arbitrary orientations and manipulated by the doctor to be better able to detect tiny changes of structures within the body. These fields, generated by passing electric currents through gradient coils, make the magnetic field strength vary depending on the position within the magnet. Protons in different tissues return to their equilibrium state at different relaxation rates.

Using a primitive NMR machine, Damadian found that there was a lag in T1 and T2 relaxation times between the electrons of normal and malignant tissues, allowing him to distinguish between normal and cancerous tissue in rats implanted with tumors. In 1971, he published the seminal article for NMR use in organ imaging in the journal Science (“Tumor Detection by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance,” March 19, 1971, vol. 171, pp. 1151-1153). Nevertheless, many individuals in the scientific and NMR community considered his ideas far-fetched, and he had few supporters at this time.

However, Damadian received a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in 1971 to continue his work. He proposed to use whole body scanning by NMR for medical diagnosis in a patent application, “Apparatus and Method for Detecting Cancer in Tissue,” filed on March 17, 1972 (U.S. Patent No. 3789832, issued Feb. 5, 1974). By February 1976, he was able to scan the interior of a live mouse using his FONAR (field focused nuclear magnetic resonance) method.