As we approach the 100th

memorial year of the Armenian Genocide of 1915, there is increasing

global interest and attention to what happened to so many Armenians.

There is also a desire to discover how much the world knew at that time.

Armenians and non-Armenians alike are seeking to better understand the

complex events of a century ago. The daily accounts from the leading

foreign press at the time—such as the New York Times, the London Times,

the Manchester Guardian, the Toronto Globe, and the Sydney Morning

Herald—can give insight into how the phases of the genocide unfolded and

how the world tried to describe the horrific sequence of events. This

was a substantial challenge, as it was before the term “genocide” had

been created to define the indescribable.

In teaching my university courses on comparative studies of genocide,

I have often asked students to study the headlines from 1915. In so

doing, they can better learn how the world began to know about such

events, struggled to comprehend such horrific deeds, and searched for

the words to describe such nightmarish scenes.

Of course, such original archival research of old newspapers can be

daunting in terms of travel, time, access, and even technology. I know

this first-hand. As a young professor in the 1980’s, I spent many hours

reading the old Toronto Globe for the year 1915. I studied column after

column and page after page of the daily newspaper coverage for the

entire year of 1915. I peered at the articles on a microfilm reader.

Systematically, I was searching for articles relating to the plight of

the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire for that fateful year. I took

careful notes and made photocopies of the most important articles. It

was an important learning experience for me as an Armenian-Canadian. It

also turned out to be a pivotal moment. From that point on, I would

start to write about the Armenian Genocide—even more so when confronted

by the troubling, ongoing denials by the Turkish government.

Fortunately for my students and I, the pioneering work has been done

by others. This means that our task today of scanning the headlines and

reading full newspaper accounts are easier, the sources more accessible.

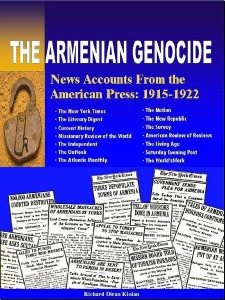

The most innovative and path-breaking work on newspaper coverage of

the genocide was conducted by Richard Kloian in his 1980 monumental

book, The Armenian Genocide: News Accounts From the American Press (1915-1922).

Working for many years to gather diverse material and employing far

less advanced technology, Kloian surveyed the American press for the key

seven-year period. He focused on coverage in the New York Times,

Current History, Saturday Evening Post, and the Missionary Review of the

World. The volume he delivered at nearly 400 pages was epic and

pioneering. It not only included a vast comprehensive account, but also a

very useful five-page chronological table listing the main headlines.

The New York Times alone accounted for over 120 articles in

1915 on the terrible plight of the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire. This

extensive coverage underlined the considerable interest by both the

press and the public, and helped ensure that substantial information was

available. It also revealed that there had been key and unprecedented

extensive access to important and timely information, often from

confidential U.S. government sources and missionary accounts. Kloian’s

book has undergone a number of editions and printings and is still

available. It is an essential reference work for anyone doing sustained

research on the Armenian Genocide. I continue to use different editions

of the book both for research and teaching.

A few years after Kloian’s influential book appeared, the Armenian

National Committee (ANC) in both Australia and Canada sought to produce

similar edited volumes for their respective countries. In 1983, the

Australian ANC printed The Armenian Genocide as Reported in the Australian Press,

a volume of just over 100 pages. It included newspaper articles from

the Age, the Daily Telegraph, Sydney Morning Herald, and World’s News.

The text was supplemented with a number of powerful photographs. A

revised edition is in progress.

In that same decade, the Canadian ANC printed the bilingual two-volume set Le Genocide Armenien Dans La Presse Canadienne/The Armenian Genocide in the Canadian Press,

providing about 280 pages of documents. Accounts were taken from

various newspapers such as the French-language Le Droit, La Presse, Le

Devoir, L’Action Catholique, and Le Canada, and the English-language

Vancouver Daily Province, Toronto Daily Star, Montreal Daily Star, the

Gazette, the Toronto Globe, Manitoba Free Press, Ottawa Evening Journal,

London Free Press, and the Halifax Herald.

A decade and half later in 2000, Katia Peltekian in Halifax, Nova Scotia, edited the 350-page book Heralding of the Armenian Genocide: Reports in the Halifax Herald, 1894-1922.

This volume covered the Hamidian massacres of the 1890’s, the Adana

massacres in 1909, and the Armenian Genocide during World War I and

after.

With great determination and skill, Peltekian has now followed up her

earlier Canadian volume with a new 1,000 page two-volume set titled, The Times of the Armenian Genocide: Reports in the British Press.

This collection covers the period 1914-23 and includes hundreds of

entries from both the Times and the Manchester Guardian. As with earlier

volumes, it contains an exceedingly useful multi-page chronological

summary of the headlines. This overview table, along with selected

excerpts, proves quite useful in the classroom setting.

For those wishing to have a scholarly annotated account of the press coverage, Anne Elbrecht published Telling the Story: The Armenian Genocide in the New York Times and Missionary Herald: 1914-1918.

Her book, a former MA thesis, was printed by Gomidas Press and offers a

chronological comparison of the press coverage in the New York Times

and the Missionary Herald. It is a highly readable volume.

Vahe Kateb’s MA thesis, “Australian Press Coverage of the Armenian

Genocide: 1915-1923,” analyzes the press coverage in Australia and

explores a number of key genocide-related themes in the Victoria-based

the Age and the Argus, Queensland’s the Mercury, and in New South Wales’

the Sydney Morning Herald. Kateb’s thesis is a valuable analytical

study that should be more widely distributed and published as a book.

As we approach 2015, at least one major new project is underway to

comprehensively collate international press coverage on the Armenian

Genocide. Rev. Vahan Ohanian, vicar general of the Mekhitarist Order at

San Lazzaro in Venice, is coordinating a multi-volume project that will

cover the Hamidian and Adana massacres and the 1915 genocide. Several

prominent genocide scholars will pen the introductions to the different

volumes. This project, along with the earlier volumes, are essential in

assisting the world to be more informed about the Armenian Genocide.

Accordingly, it would be helpful if university libraries and Armenian

community centers and schools acquired these volumes. They will help us

to remember 1915 and prepare for the historic memorial year of 2015.

List of publications mentioned in article

Richard Kloian, The Armenian Genocide: News Accounts From the American Press (1915-1922) (Anto Printing, Berkeley, 1980 [1st], 1980 [2nd], 3rd [1985]), 388 pages for 3rd edition; also Heritage Publishing, Richmond, n.d.; with 392 pages).

Armenian National Committee, The Armenian Genocide as Reported in the Australian Press (ANC, Willoughby/Sydney, 1983; 119 pages)

Armenian National Committee of Canada, Le Genocide Armenien Dans La Presse Canadienne/The Armenian Genocide in the Canadian Press, Vol. 1, 1915-1916 (ANCC, Montreal, 1985; 159 pages).

Armenian National Committee of Canada, Le Genocide Armenien Dans La Presse Canadienne/The Armenian Genocide in the Canadian Press, Vol. I1, 1916-1923 (ANCC, Montreal, n.d. c1985; 121 pages).

Katia Peltekian, Heralding of the Armenian Genocide: Reports in the Halifax Herald, 1894-1922 (Armenian Cultural Association of the Atlantic Provinces, Halifax, 2000; 352 pages).

Katia Peltekian, The Times of the Armenian Genocide: Reports in the British Press, Vol. 1: 1914-1919 (Four Roads, Beirut, 2013; 450 pages/976 pages total for two volumes).

Katia Peltekian, The Times of the Armenian Genocide: Reports in the British Press, Vol. 2: 1920-1923 (Four Roads, Beirut, 2013; 426 pages/976 pages total for two volumes).

Anne Elbrecht, Telling the Story: The Armenian Genocide in the New York Times and Missionary Herald: 1914-1918 (London, Gomidas, 2012; 235 pages).

Vahe Kateb, “Australian Press Coverage of the Armenian Genocide: 1915-1923” (MA thesis, University of Wollongong, 2003)

Monday, December 30, 2013

Wednesday, December 25, 2013

Thoughts on Threshold of Centennial

As we approach

2015, the 100th anniversary of the annihilation of the Armenian presence

from their homeland of 4,000 years, we see major activities being

planned by both Turkey and Armenians.

When Turkish acquaintances ask me what Armenians, especially the “evil diaspora,” are planning to do in 2015, I say they are planning programs to assert the historical facts about the vanishing of Armenians from Anatolia in 1915. Then I turn around with a question of my own: “What are the Turks doing?” Their short answer is that the Turks will continue to dismiss the “misinformation’’ that the Armenians are disseminating.

Thus, the Armenians in Armenia and the diaspora are redoubling their efforts to have the genocide recognized worldwide, while the Turks are continuing to pour more money and resources into their official denialist policy both within and outside Turkey. In an attempt to divert global attention from the genocide commemoration, Turkey has decided to promote the 100th anniversary of the World War I Gallipoli campaign, to be showcased as an historic event through government-supported activities worldwide and hailed as the “heroic resistance of the Turkish forces against the onslaught of the imperialistic powers at the Dardanelles Strait.”

One can easily deduce from these opposing strategies and efforts that the main stumbling block for Turkey and Armenia, as neighbors, in normalizing their relationship and the reconciliation of their respective civil societies is the divergence of both the interpretation and understanding of their shared history. The result is an impasse. By this time next year, I doubt there will be much change and the impasse will go on. The issue will continue to be treated as a political match, with points scored for Turkey if Obama continues saying “Medz Yeghern,” and points for Armenia if he says “Genocide.”

There are geopolitical, military, and economic reasons for the status quo to continue. Armenia may not be influential enough to overcome any of these reasons at present. Be that as it may, I believe Armenians can be more effective if they re-channel their resources, which are extremely limited in comparison to Turkey, in this struggle.

I see two main areas when Armenians can make some headway on this issue. In my humble opinion, neither one is addressed properly by Armenia and Armenians.

The first target in dealing with the genocide issue is the academic field, which is supposed to arrive at indisputable historic facts after thorough and objective research of a multitude of state archives, documents, communication records, and oral history findings. The struggle in this field regarding the Armenian Genocide can best be summarized as forces of truth versus money and power. On one side there is truth, defended by almost all of the international academia; on the other side, there is the falsification of truth by a handful of scholars generously rewarded with funds provided by the Turkish state.

The second target in dealing with the genocide issue is the general population of Turkey, with the objective of conveying to them the historical truth of 1915 and its consequences, which are still felt today. This truth is best served when delivered to the people of Turkey in Turkish, based on archival material and historic facts—from the 1880′s to 1922—directly from Turkish sources and their allies, including the factual consequences of the ongoing cover-up and denial by the state.

Academically, the only organization that spearheads and organizes objective research by independent scholars on this topic is the Zoryan Institute with its subsidiary, the International Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies. For the past 30-plus years, it has provided the highest standards of scholarship and objectivity in undertaking multi-disciplinary research and analysis. This includes documentation, lectures, conferences, and publications in seven languages related to human rights and genocide studies. The publications include more than 40 books, some of which are in several languages, and 2 major periodicals, with one dealing with genocide studies and the other the diaspora.

In addition, the Zoryan Institute provides research assistance to scholars, writers, journalists, filmmakers, government agencies, and other organizations. When Zoryan published Wolfgang Gust’s The Armenian Genocide 1915/16: Documents from the Diplomatic Archives of the German Office in German, English, and Turkish, prominent Turkish journalist Mehmet Ali Birand could only reflect: “When you read and study these documents, even if this is your first venture into this subject, there is no way you will deny the genocide and disagree with the Armenians.”

Even though the Turkish state defines Zoryan as a “propaganda center,” several scholars from Turkey have attended the Genocide and Human Rights University Program run by the Zoryan Institute at the University of Toronto, and many of them have become outspoken advocates of historic truth within Turkey and the rest of the world.

To best describe Zoryan’s contribution to scholarship is to quote from the “plea” made by the International Scholars of Genocide and Human Rights Studies last year in support of Zoryan’s fundraising activities: “For the past 30 years, the Institute has maintained an ambitious program to collect archival documentation, conduct original research, and publish books and periodicals. It also conducts university-level educational programs in the field of genocide and human rights studies, taking a comparative and interdisciplinary approach in its examination of the Jewish Holocaust, the Cambodian Genocide, and the Rwandan Genocide, among others, using the Armenian Genocide as a point of reference. In the process, using the highest academic standards, the Institute has strived to understand the phenomenon of genocide, establish the incontestable, historical truth of the Armenian Genocide, and raise awareness of it among academics and opinion-makers. In the face of the continuing problem of genocide in the 21st century, the Institute is to be commended for its service to the academic community and is recognized by scholars for providing leadership and a support structure in promoting the cause of universal human rights and the prevention of genocide.”

Despite its herculean efforts and outstanding results, the Zoryan Institute receives no appreciable financial support or acknowledgment from major Armenian organizations or the state. The institute is supported entirely by private donations. Against it, there exists the full power and unlimited funds of the Turkish state, and more recently the Azerbaijan state, which attempts to lure scholars to rewrite history. As a result, the Turkish State Historic Society reduces the number of 1915 Armenian victims with every new publication; at last count, a few thousand Armenians died of illness and hunger, while the number of Turkish victims of “genocide” perpetrated by the Armenians increases every year and is now more than two million. By the same strategy, the number of Azeri dead in the Khojalu “genocide” keeps increasing with every publication.

Dialogue between two conflicting parties can be meaningful only after both are aware of the truth and the facts. Even though the Turkish state has not allowed the truth to come out until recently, there are now clear signs that the taboos about 1915 are finally being broken and that there is an emerging “common body of knowledge” among Turkish citizens and, more importantly, among the opinion makers. Zoryan contributed immensely to the development of this “common body of knowledge” through conferences, seminars, and the books it helped publish by such authors as Yair Auron, Taner Akcam, Wolfgang Gust, Roger Smith, Vahakn Dadrian, and Rifat Bali.

Given all this, I strongly urge Armenians to support the Zoryan Institute so that it can continue to develop the common body of knowledge to be shared by Armenians and Turks. Hopefully, shared history will help these neighboring peoples reconcile with their pasts, and such reconciliation will help secure a future for generations to come.

I will elaborate on the second target—the population of Turkey—and its challenges in a separate article.

When Turkish acquaintances ask me what Armenians, especially the “evil diaspora,” are planning to do in 2015, I say they are planning programs to assert the historical facts about the vanishing of Armenians from Anatolia in 1915. Then I turn around with a question of my own: “What are the Turks doing?” Their short answer is that the Turks will continue to dismiss the “misinformation’’ that the Armenians are disseminating.

Thus, the Armenians in Armenia and the diaspora are redoubling their efforts to have the genocide recognized worldwide, while the Turks are continuing to pour more money and resources into their official denialist policy both within and outside Turkey. In an attempt to divert global attention from the genocide commemoration, Turkey has decided to promote the 100th anniversary of the World War I Gallipoli campaign, to be showcased as an historic event through government-supported activities worldwide and hailed as the “heroic resistance of the Turkish forces against the onslaught of the imperialistic powers at the Dardanelles Strait.”

One can easily deduce from these opposing strategies and efforts that the main stumbling block for Turkey and Armenia, as neighbors, in normalizing their relationship and the reconciliation of their respective civil societies is the divergence of both the interpretation and understanding of their shared history. The result is an impasse. By this time next year, I doubt there will be much change and the impasse will go on. The issue will continue to be treated as a political match, with points scored for Turkey if Obama continues saying “Medz Yeghern,” and points for Armenia if he says “Genocide.”

There are geopolitical, military, and economic reasons for the status quo to continue. Armenia may not be influential enough to overcome any of these reasons at present. Be that as it may, I believe Armenians can be more effective if they re-channel their resources, which are extremely limited in comparison to Turkey, in this struggle.

I see two main areas when Armenians can make some headway on this issue. In my humble opinion, neither one is addressed properly by Armenia and Armenians.

The first target in dealing with the genocide issue is the academic field, which is supposed to arrive at indisputable historic facts after thorough and objective research of a multitude of state archives, documents, communication records, and oral history findings. The struggle in this field regarding the Armenian Genocide can best be summarized as forces of truth versus money and power. On one side there is truth, defended by almost all of the international academia; on the other side, there is the falsification of truth by a handful of scholars generously rewarded with funds provided by the Turkish state.

The second target in dealing with the genocide issue is the general population of Turkey, with the objective of conveying to them the historical truth of 1915 and its consequences, which are still felt today. This truth is best served when delivered to the people of Turkey in Turkish, based on archival material and historic facts—from the 1880′s to 1922—directly from Turkish sources and their allies, including the factual consequences of the ongoing cover-up and denial by the state.

Academically, the only organization that spearheads and organizes objective research by independent scholars on this topic is the Zoryan Institute with its subsidiary, the International Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies. For the past 30-plus years, it has provided the highest standards of scholarship and objectivity in undertaking multi-disciplinary research and analysis. This includes documentation, lectures, conferences, and publications in seven languages related to human rights and genocide studies. The publications include more than 40 books, some of which are in several languages, and 2 major periodicals, with one dealing with genocide studies and the other the diaspora.

In addition, the Zoryan Institute provides research assistance to scholars, writers, journalists, filmmakers, government agencies, and other organizations. When Zoryan published Wolfgang Gust’s The Armenian Genocide 1915/16: Documents from the Diplomatic Archives of the German Office in German, English, and Turkish, prominent Turkish journalist Mehmet Ali Birand could only reflect: “When you read and study these documents, even if this is your first venture into this subject, there is no way you will deny the genocide and disagree with the Armenians.”

Even though the Turkish state defines Zoryan as a “propaganda center,” several scholars from Turkey have attended the Genocide and Human Rights University Program run by the Zoryan Institute at the University of Toronto, and many of them have become outspoken advocates of historic truth within Turkey and the rest of the world.

To best describe Zoryan’s contribution to scholarship is to quote from the “plea” made by the International Scholars of Genocide and Human Rights Studies last year in support of Zoryan’s fundraising activities: “For the past 30 years, the Institute has maintained an ambitious program to collect archival documentation, conduct original research, and publish books and periodicals. It also conducts university-level educational programs in the field of genocide and human rights studies, taking a comparative and interdisciplinary approach in its examination of the Jewish Holocaust, the Cambodian Genocide, and the Rwandan Genocide, among others, using the Armenian Genocide as a point of reference. In the process, using the highest academic standards, the Institute has strived to understand the phenomenon of genocide, establish the incontestable, historical truth of the Armenian Genocide, and raise awareness of it among academics and opinion-makers. In the face of the continuing problem of genocide in the 21st century, the Institute is to be commended for its service to the academic community and is recognized by scholars for providing leadership and a support structure in promoting the cause of universal human rights and the prevention of genocide.”

Despite its herculean efforts and outstanding results, the Zoryan Institute receives no appreciable financial support or acknowledgment from major Armenian organizations or the state. The institute is supported entirely by private donations. Against it, there exists the full power and unlimited funds of the Turkish state, and more recently the Azerbaijan state, which attempts to lure scholars to rewrite history. As a result, the Turkish State Historic Society reduces the number of 1915 Armenian victims with every new publication; at last count, a few thousand Armenians died of illness and hunger, while the number of Turkish victims of “genocide” perpetrated by the Armenians increases every year and is now more than two million. By the same strategy, the number of Azeri dead in the Khojalu “genocide” keeps increasing with every publication.

Dialogue between two conflicting parties can be meaningful only after both are aware of the truth and the facts. Even though the Turkish state has not allowed the truth to come out until recently, there are now clear signs that the taboos about 1915 are finally being broken and that there is an emerging “common body of knowledge” among Turkish citizens and, more importantly, among the opinion makers. Zoryan contributed immensely to the development of this “common body of knowledge” through conferences, seminars, and the books it helped publish by such authors as Yair Auron, Taner Akcam, Wolfgang Gust, Roger Smith, Vahakn Dadrian, and Rifat Bali.

Given all this, I strongly urge Armenians to support the Zoryan Institute so that it can continue to develop the common body of knowledge to be shared by Armenians and Turks. Hopefully, shared history will help these neighboring peoples reconcile with their pasts, and such reconciliation will help secure a future for generations to come.

I will elaborate on the second target—the population of Turkey—and its challenges in a separate article.

Thursday, December 19, 2013

What I Choose It to Mean: On ‘Yeghern’ as the Armenian Translation of ‘Genocide’

“The term Yeghern, or Medz Yeghern,

is the only word that really captures the essence of what happened in

1915. The survivors used that word. It is the only word that could

really explain what happened in 1915. In a world without genocide

denial, it would be the best word.”

–Khatchig Mouradian (2009)1

–Khatchig Mouradian (2009)1

‘Medz Yeghern’: the Proper Name of the Genocide

In the concluding installment of this study on the semantics, history, and politics of the phrase Medz Yeghern, it is crucial to underscore that the exhausting search for recognition should not block the use of the words that our ancestors have bequeathed us. It has been argued that recognition has been sufficiently ensured by two resolutions of the House of Representatives, 3 federal court rulings, 42 state declarations by legislation or proclamation, a sentence in a document filed in 1951 by the U.S. government to the International Court of Justice and another sentence in Ronald Reagan’s proclamation,2 along with official declarations by 20 countries and statements of a host of scholars. “We don’t say that this is the end and the work of recognition has been done; simply, the emphasis should be put on reparation and the rights,” Giro Manoyan, the head of the ARF Bureau Armenian Cause office, declared recently.3

Armenians should not be obfuscated by denial, whether mainstream or from a lunatic fringe, which will probably be as lasting as affirmation. Another worrisome trend—misuse—should not obfuscate them either.

The systematic and premeditated annihilation of 1915-17 became one of the catalysts to Lemkin’s initial formulation of genocide—still without its name—in 1933. Thus, the particular (Medz Yeghern) gave birth to the general (tseghasbanutiun, “genocide”). However, I will allow myself to repeat that the common noun tseghasbanutiun is the legal term applied to any act of systematic and premeditated annihilation, from Namibia to Darfur and from Cambodia to Rwanda, and not the proper noun of the Armenian annihilation: in Armenian, the use of հրէական ցեղասպանութիւն (hreagan tseghasbanutiun, “Jewish genocide”), for instance, is as legitimate as հայկական ցեղասպանութիւն (haygagan tseghasbanutiun, “Armenian genocide”).

For instance, The French and Armenian inscriptions on the 1987 genocide memorial in Valence, France, read: “A la mémoire des 1.500.000 Armeniens victimes du genocide perpetré par l’état turc en 1915” / “Ի յիշատակ մէկ ու կէս միլիոն հայերու ցեղասպանութեան կատարուած 1915ի թուրք պետութեան կողմէ” (“In the memory of the 1,500,000 Armenians victims of the genocide perpetrated by the Turkish state in 1915”).

Clearly, “genocide” and tseghasbanutiun are the legal qualifiers of the act, not the actual name, a fact noticeable in both versions; the Armenian says: “In the memory of the genocide of one and a half million Armenians perpetrated by the Turkish state of 1915.” The proper noun is disclosed when tseghasbanutiun is paired with Medz Yeghern, as in the opening lines of the Armenian monolingual inscription beneath the khatchkar (cross-stone) in front of the Armenian Prelacy of Canada, in Montreal: «Կանգնեցաւ / “Կարմիր Աւետարան” խաչքար-յուշակոթողս / սրբազան նահատակաց հայոց /

Մեծ Եղեռնի ցեղասպանութեան 90-ամեակին առթիւ / 24 Ապրիլ, 2005… » (“This khachkar-memorial, ‘Red Gospel,’ was erected to the sacred martyrs of the Armenians on the occasion of the 90th anniversary of the genocide [tseghasbanutiun] of the Medz Yeghern, April 24, 2005…”).

The legal term tseghasbanutiun qualifies the legal term Medz Yeghern (“Great Crime”) in the same way that “genocide” qualifies the (non-legal) term Shoah (“Catastrophe”) in the title of Zeev Garber’s book, Shoah, the Paradigmatic Genocide: Essays in Exegesis and Eisegesis (University Press of America, 1994). The capitalization of the common noun tseghasbanutiun does not turn it into a proper noun, and the capitalization of “genocide” does not make “Armenian Genocide” a proper noun either, in the same way that the capitalization of “holocaust” does not turn “Holocaust” into a proper noun. “Armenian Genocide” is, thus, a sobriquet: a common name that conceals our proper name. Borrowing the words of literary scholar Marc Nichanian, we have to acknowledge that “Today, they [Armenians] are using a common name as a proper name. They do not respect the identity of the Event that has shaped them for the past 80 years. They do not respect their own memory of the Event.”4

Medz Yeghern may be used legitimately and in good faith instead of or alongside “Armenian Genocide,” as Shoah is currently used legitimately and in good faith instead of or alongside “Jewish Holocaust” by any number of non-Jews. Indeed, neither Shoah nor Holodomor, neither Porrajmos nor Sayfo, make the experience of their original users any more unique than Medz Yeghern; all of them are proper nouns of an event in history—regardless of any metahistorical interpretation—like Glorious Revolution, Renaissance, Risorgimento or Reconquista.

‘Yeghern’ = Genocide from 1965 to 2013

It is worthy to remember that word meanings are not etched in stone (for example, English gay meant “merry, happy, carefree” before it dropped out of use after the incorporation of the slang meaning “homosexual”).5 An unprejudiced examination of linguistic facts shows that over the past 50 years, while tseghasbanutiun was becoming the automatic translation of the legal term “genocide,” with other calques like azkasbanutiun or zhoghovrtasbanutiun falling along the way, the road from the particular to the general was also widening the semantic perception of yeghern. During the past hundred years, Armenian-English dictionaries have crossed the realm of “crime,” passed by “massacre” (Medz Yeghern was translated as “Great Massacre,” for instance, in 1965),6 and even stopped by yeghern as “holocaust” in 2006.7 The translation “holocaust” is not just a whim of dictionary writers; we may note its use, for instance, in a bilingual booklet by writer Levon K. Daghlian (1976),8 an article by literary scholar Vahé Oshagan (1985),9 and a translation by Harvard professor James R. Russell (2012).10

Therefore, it is not surprising that yeghern has reached the meaning “genocide.” In a study written and published in 1965, survivor historian Hagop Dj. Siruni (1890-1973) combined yeghern and premeditation and, thus, showed to have adopted yeghern as a translation of “genocide”: “The Armenian-exterminating yeghern was neither the result of a casual inspiration nor the consequence of the pretexts that the Ittihad constantly put forward; there is a whole pile of proofs that reveals the terrible premeditation (կանխամտածութիւն, gankhamdadzutiun).”11

The meaning of “genocide” for yeghern was occasionally used over the years. For example, a section of Patma-banasirakan handes, the flagship publication of the Armenian Academy of Sciences, was devoted to the 60th anniversary of the genocide under the title, “Yeghern yev veradznunt. 1915-1975” (Russian: “Genotsid i vozrozhdeniye. 1915-1975”; English: “Genocide and Revival. 1915-1975”). In the same issue, a chronicle of an official homage at the monument to the victims of Tzitzernakaberd, entitled “Yegherni zoheri hushartzanum,” became “V pamyatnika zhertam genotsida” in Russian and “At the Memorial of the Victims to the Genocide” in English.12

Since the beginning of the Karabagh movement, the impact of the pogrom of Sumgait in February 1988 created the parallel with 1915. The synonymous character of yeghern and tseghasbanutiun as the Armenian term for “genocide” was underscored and reinforced in an unprecedented way. American anthropologist Nora Dudwick watched the process first-hand and noted, “It seemed that every social and political problem took on additional significance as containing a threat to the Armenians’ continued existence as a people.”13 The Armenian-language banners raised during the huge demonstrations in Yerevan reflected the perceived existential threat very explicitly. One asked “To Recognize the Medz Yeghern of 1915,” and another stated that “Sumgait is the Follow-Up to the Medz Yeghern.” Yet another made the link between both: “If the USSR Government Had Recognized the Genocide [tseghasbanutiun] of 1915, Sumgait Would Not Have Happened in 1988”.14

Dudwick referred to the use of “white genocide,” “cultural genocide,” and “ecological genocide” in the banners.15 The Armenian word chosen to rhetorically enlarge the concept of “genocide” to assess political and social events was not tseghasbanutiun, however, but yeghern, as in the ecological struggle against the chemical giant “Nayirit” (“Down with the Yeghern of Nayirit”), the diminishing utilization of the Armenian language (“To Betray the Language Is a White Yeghern”), or the destruction of Armenian historical monuments outside the borders of Soviet Armenia (“The Destruction of Historical Monuments Is a Spiritual [hokevor, figuratively “cultural”] Yeghern”). Any counterargument that yeghern equals “massacre” here should be regarded as a stretch of the truth; Dudwick’s would have hardly translated “genocide” without relying on local informants. Moreover, a banner that mocked the Soviet slogan of “peoples’ friendship” used yeghern as unequivocal synonym of tseghasbanutiun, “What Friendship after the Yeghern of 1915-1988,” the same as another that stressed the rights of the population of Mountainous Karabagh: “By Respecting the Inalienable Right to Self-Determination of the Karabaghis, We Prevent the New Yeghern [Nor Yegherne], Red and White.”16

Lawrence Sheets, currently the South Caucasus project director of the International Crisis Group, recently recounted his visit to Armenia as South Caucasus correspondent for Reuters in 1992. He described the mindset created by the Karabagh conflict: “In this woman’s mind (and those of many others), it was all part of the same pattern: The Karabagh war was just another Turkish effort to exterminate them, a logical extension of the almost-impossible-to-fathom Mets Yeghern (genocide) of an estimated 1.5 million Armenians at the hands of the dying Ottoman Empire (present-day Turkey) during World War I.”17 His use of “Mets Yeghern (genocide)” clarified the meaning of the word in the same way as “Ottoman Empire (present-day Turkey).” He recorded the name of the event as it had been spelled to him, after many banners had already used yeghern to mean “genocide.”

In the 21st century, the Shoah (Holocaust) memorial installed in downtown Yerevan by the Jewish community of Armenia (2006) displays a bilingual inscription with two totally different texts in Hebrew and Armenian. The Hebrew writing declares: “Lihyot o Lishkoakh / Lizkor Korbanot ha-Shoah” (“To be or to forget / In memory of the victims of the Shoah”).

The members of the Jewish community, who are citizens of the republic and fluent in Armenian, had tactfully chosen to memorialize the victims of both genocides in the Armenian text: “Ապրել / Չմոռանալ / Հայ եւ հրեայ ժողովուրդների եղեռնի յիշատակին” (“To live / Not to forget / In memory of the yegherns of the Armenian and Jewish peoples”).

It would be unreasonable to assume that such homage downplayed the magnitude of both genocides and stated “crime” or even “massacre” (the word chart would have sufficed) in the heart of Yerevan. Here, yeghern could only mean “holocaust” or “genocide,” the same as Shoah, and each of those two meanings underscores their unique nature. The translation by epress.am confirmed it: “To live and not to forget: In the memory of the Armenian and Jewish peoples’ Genocide [Yeghern].”18

The identification of both concepts yeghern and tseghasbanutiun has evolved in fully unexpected ways. Residents of various streets in central Yerevan, who have seen their houses expropriated in recent years, staged a demonstration near the presidential residence in January 2012, when the French law draft against genocide denial was initially approved. A spokesperson for them stated: “The law draft approved by France has not made me happy at all, because today a white yeghern [spitak yeghern] is being carried in my homeland, while the authorities and the people are watching in silence. What do we do? Should we go and ask the French to recognize the white genocide [spitak genotsid] of today? How to be happy, when people are being expelled from their own homes and thrown to the street in our country? Let’s approve a law to establish criminal punishment to those who deny the ‘white genocide’ [spitak genotsid] in Armenia. What do you think, will it pass in Armenia?”19

The excerpt has the sole purpose of pointing out the abovementioned identification (spitak yeghern = spitak genotsid), regardless of the degree of hyperbole. Its echo, among many other examples, was found in an editorial entitled, “What Is Going on Today in Armenia Is a White Yeghern” of the Yerevan-based newspaper Haykakan Zhamanak (April 25, 2013): “People very frequently and easily claim that what is going on today in Armenia is a white Yeghern, an internal genocide [tseghasbanutiun], that the Turk massacred the Armenians in Western Armenia and the authorities of the Republic of Armenia are doing that in the Republic of Armenia…”20 The quotes show that the wording spitak yeghern identifies yeghern and genocide because its users claim that the situation was planned; as a matter of fact, it is not an Eastern Armenian adaptation of the expression spitak chart (“white massacre”), frequently used in Armenian rhetoric to symbolize assimilation in the diaspora.

References to yeghern = tseghasbanutiun = “genocide” going back to 1965 may provide a context to Armenian president Serge Sarkisian’s line on Feb. 5, 2013, that “those two words are the same for us.”21 Additionally, the Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute’s website in Yerevan has entitled its section on the destruction of Armenian cultural monuments by the Turkish state, Mshakutayin Yeghern (in English, Cultural Genocide; Turkish, Kültürel Soykırım) and employs tseghasbanutiun six times in the text. Neither the demonstrators at Freedom Square in 1988 nor the Genocide Museum in 2013 may be suspected of exploiting yeghern with the aim of “undermining several decades of extensive lobbying efforts for the recognition of the Armenian Genocide.”22

The advice to look it up in a dictionary23 seems equally moot. Linguist Ashot Sukiasyan (1922-2007) included tseghasbanutiun among synonyms of yeghern in the second edition of his monumental thesaurus of the Armenian language (2003, reprinted in 2009).24 Yeghern appears as “genocide” in an Armenian-English dictionary published in Yerevan in 2009; its five authors had also translated tseghasbanutiun as “genocide.”25The list is likely longer.

The use of yeghern and tseghasbanutiun as synonyms by current Armenian speakers should induce their Armenian American critics to hone their linguistic skills, as a pioneering Turkish denier in America, former ambassador and MP Mustafa Šükrü Elekdağ, had already done by 2009-10.

Levy, Davutoğlu, and their ‘Helpers’

Moreover, heads of state (Barack Obama) who use Medz Yeghern and, more times than not, couple it with genocide (Pope John Paul II, Stephen Harper) are probably showing the way for Armenian pundits, political operators, and the community at large to get thoroughly acquainted with their ancestral tongue. It is fair to say that setting the record straight with the legal term Great (Evil) Crime in late 2008 or early 2009 would have thwarted the “calamity” scenario installed by the Turkish “apology campaign.” Insistence on the synonymous character of Medz Yeghern and genocide—an insistence that should have been expected from, but not be limited to, the president of Armenia as the counterpart of the U.S. president—could have also made White House advisers and speechwriters desist from including Medz Yeghern in presidential statements between 2009 and 2013; as we already took note in a previous article, they used it since “one side” (e.g., the Turkish one) had admitted it as a “place marker.” Such insistence would have been crucial to avoid its worldwide banalization and deformation. Unfortunately, history can only be written in past tense and not in conditional mode.

Additionally, history seems to be written by the winners, as it happened, most recently, in Movsesian v. Victoria Versicherung. After the successful appeal by the Armenian side on December 2010, the defendant appealed in January 2011 and argued that Medz Yeghern was not “the term for ‘Armenian Genocide’ in the Armenian language,” as the majority panel had declared, because it was “generally translated as ‘great calamity,’ not ‘genocide.’” The authority for this argument was Ben Schott’s blog entry in The New York Times, based on Turkish columnist Ali Bulaç’s view that the “best translation” of Medz Yeghern is “Great Calamity.”26 The defendant-appellant also transcribed samples of criticism against the term “by many in the Armenian community precisely because it does not mean ‘Armenian genocide.’” Citing the September 2009 amicus brief from the Armenian Bar Association and the Armenian National Committee of America (ANCA), in which it was stated that President Barack Obama had used Medz Yeghern, “the Armenian name for the Armenian Genocide,” the defendant-appellant retorted: “That representation to the panel by the ANCA simply cannot be squared with its prior objection that the terms have fundamentally different meanings.”27

People not conversant in the Armenian language have been allowed to impose their ignorance over our half-baked knowledge, inadequately suited to engage the challenges posed by recently developed and more sophisticated mechanisms of soft-core relativism or denial.

In this regard, let us consider the following lines by political scientist Guenter Lewy on the genocide of the Native Americans: “In the end, the sad fate of America’s Indians represents not a crime but a tragedy, involving an irreconcilable collision of cultures and values. … To fling the charge of genocide at an entire society serves neither the interests of the Indians nor those of history.”28 The replacement of “America’s Indians” by “Ottoman Armenians” exposes the grounds for Lewy’s denial, couched in flawed academic methodology,29 in his book on the Armenian “disputed genocide”: the rejection of the malevolent design characteristic of crime, in favor of tragedy or “calamity” which may occur independently of such design.

Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu recently upheld the same rejection: “I would not call genocide what was lived through, but it is their choice for those who call it. We need to develop a new language on this issue. We are not denying your pain, we understand; whatever that needs to be done, let’s do it together. But this is not a unilateral declaration of a crime.”30 Since 2009, his ministry has routinely condemned “President Barack Obama’s standard ‘Medz Yeghern (Great Disaster)’ reference to the Armenian Genocide and criticized the U.S. for being prejudiced about 1915,” as noted by Turkish columnist Burak Bekdil, who did not refrain from using Medz Yeghern and genocide in the same sentence.31 Here is a sample from 2013: “Issued under the influence of domestic political considerations and interpreting controversial historical events on the basis of one-sided information and with a selective sense of justice, such statements damage both Turkish-American relations, and also render it more difficult for Turks and Armenians to reach a just memory.”32

On the other side of the divide, it is highly interesting that, in its February 2011 response, the plaintiff-appellee in Movsesian v. Victoria Versicherung had a moment of epiphany: It quoted the relevant paragraph of Senator Barack Obama’s 2006 letter to Condoleeza Rice about the recognition of the Armenian Genocide, including the use of these two words, to bring forward the noteworthy argument that “President Obama reasserted this view in 2009.”33 Unheard before or since, this is the same conclusion we arrived at quite independently in a previous article. Noticeably, even a misnamed “great disaster” with an additional attachment of “one of the worst atrocities of the twentieth century” with “1.5 million Armenians massacred or marched to their deaths” is tantamount, for the Turkish government, to “a unilateral declaration of a crime” and “one-sided information.” An accurately named Great Crime would have an even a greater impact.

Gabriel Sanders recently ended his review of Raphael Lemkin’s autobiography with the following reflection: “Critics can argue that Lemkin accomplished nothing. Genocide marches on. But Rwanda and Srebrenica are not refutations of his legacy; they are affirmations of his prescience. Without Lemkin, they would have been atrocities. In the light of his Genocide Convention, they were crimes.”34 In the light of the Genocide Convention, one may ask, what would the Great (Evil) Crime of 1915 be?

As the “great calamity” hoax goes marching on, scholars like Lewy and politicians like Davutoğlu may enlist the logical support of Turkish sources to their thesis and, moreover, approvingly nod to those Armenian sources that continue to recycle statements such as, “at the end of the day, ‘Meds Yeghern’ is meaningless for most Americans, and does not have a judicial meaning.”35

Diplomat and political scientist Ara Papian has observed that “‘Medz Yeghern’ means genocide for us, but it doesn’t mean genocide to the rest of the world.”36 In this context, the well-known paragraph of Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass deserves to be recalled once again: “‘When I use a word,’ Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, ‘it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.’

“‘The question is,’ said Alice, ‘whether you can make words mean so many different things.’

“‘The question is,’ said Humpty Dumpty, ‘which is to be master—that’s all.’”37

Our words can only mean what we, the masters of the language, have chosen them to mean. An innocent mistranslation of Medz Yeghern may be a mistake, but a tendentious mistranslation is a violation of the Armenian language.

Medz Yeghern and its real and legal meaning of “Great (Evil) Crime” (as well as its contemporary meaning of “genocide”) are the only legitimate choice over the fictitious and non-legal meaning of “Great Calamity” and its variants “Great Catastrophe,” “Great Tragedy,” or even the linguistically inaccurate “Great Atrocity.” Relentless repetition installed “Medz Yeghern (Great Calamity)” within the international media; a barrage of the continuous use of “Medz Yeghern, the Armenian Genocide,” with or even without its literal translation of “Great (Evil) Crime,” should help install it anywhere.

In the end, any pretense of “denialist terminology” to refrain from calling things by their 90-plus-year-old Armenian proper name—as it has been misguidedly suggested following presidential statements of “Meds Yeghern” and Turkish mistranslations of “Great Calamity”—would be an act of self-censorship, playing straight into the hands of the denier. Moreover, it would be the most tragic irony in the ultimate stage of genocide: denial unwittingly self-imposed by those who are bound to fight against denial.

Notes

1 Quoted in The Armenian Reporter, June 26, 2009.

2 The Armenian Weekly, June 5, 2012.

3 Hayastani zrutsakits, April 19, 2013.

4 David Kazanjian and Marc Nichanian, “Between Genocide and Catastrophe,” in David Kazanjian and David Eng (eds.), Loss: the Politics of Mourning, Los Angeles and Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003, p. 127.

5 Mark Perlman, Conceptual Flux: Mental Representation, Misrepresentation, and Concept Change, Dordrecht: Kluwer, 2000, p. 182.

6 From Catholicos Vazken I’s message: “Today, 50 years after the Great Massacre…” (“The Message of His Holiness the Catholicos of All Armenians in the Sad Anniversary,” Aregak, special issue, April 1965, p. 5).

7 Nicholas Awde and Vazken-Khatchig Davidian, Western Armenian Dictionary and Phrasebook, New York: Hippocrene Books, 2006, p. 58.

8 Levon K. Daghlian, Yegherni husher/Memories of the Holocaust, Boston: Haig H. Toumayan, 1976.

9 Vahe Oshagan, “The Theme of the Armenian Genocide in Diaspora Prose,” Armenian Review, Spring 1985, pp. 53-54.

10 James R. Russell, “The Bells: From Poe to Sardarapat,” Journal of the Society for Armenian Studies, vol. 21 (2012), p. 153.

11 H. Dj. Siruni, “Yeghern me yev ir patmutiune” (A Yeghern and Its History), Ejmiatzin, February-March-April 1965, p. 7.

12 Patma-banasirakan handes, 2, 1975, pp. 264, 267 (index of contents).

13 Quoted in Mark Malkhasian, Gha-ra-bagh! The Emergence of the National Democratic Movement in Armenia, Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1996, p. 56.

14 Harutiun Marutyan, “Tseghaspanutian hishoghutiune vorpes nor inknutian tsevavorich (1980 tvakanneri verj – 1990 tvakanneri skizb)” (The Memory of Genocide as Marker of New Identity: Late 1980s – Early 1990s), Patma-banasirakan handes, 1, 2005, p. 59.

15 Malkhasian, Gha-ra-bagh!, p. 56.

16 Marutyan, “Tseghaspanutian hishoghutiune,” pp. 61, 63.

17 Lawrence Scott Sheets, Eight Pieces of Empire: A 20-Year Journey Through the Soviet Collapse, New York: Crown Publishers, 2011, p. 131.

18 See www.epress.am/en/2010/10/20/city-staff-busy-cleaning-traces-of-anti-semitism-on-yerevans-holocaust-memorial.html, where it is mistakenly said that the inscription is the same in both Hebrew and Armenian.

19 See www.epress.am/2012/01/25.

20 See www.hartak.am/arm/index.php?id=1982.

21 See www.panarmenian.net/arm/news/144433/.

22 The Armenian Weekly, Feb. 12, 2013.

23 Asbarez, Feb. 6, 2013.

24 Ashot Sukiasian, Hayots lezvi homanishneri batsatrakan bararan (Explanatory Dictionary of Synonyms of the Armenian Language), second edition, Yerevan: Yerevan State University Press, 2003, p. 264.

25 Sona Seferian et al., English-Armenian, Armenian English Dictionary, Yerevan: Areg, 2009, pp. 456, 569.

26 The New York Times, May 6, 2009.

27 See http://cdn.ca9.uscourts.gov/datastore/uploads/07-56722pfr.pdf.

28 Guenter Lewy, Essays on Genocide and Humanitarian Intervention, Salt Lake City: Utah University Press, 2012, p. 102.

29 See Taner Akçam, “Review Essay: Guenter Lewy’s The Armenian Massacres in Ottoman Turkey,” Genocide Studies and Prevention, April 2008, pp. 111-145.

30 Milliyet, July 7, 2012.

31 Hurriyet Daily News, May 1, 2013.

32 Hurriyet Daily News, April 24, 2013.

33 See http://cdn.ca9.uscourts.gov/datastore/uploads/07-56722pfr.pdf.

34 The Forward, Aug. 2, 2013.

35 Haykaram Nahapetyan, “Obama vs Romney: Armenian American Community Pressures Candidates to Recognize 1915 Genocide by Ottoman Turkey,” PolicyMic, Sept. 29, 2012 (www.policymic.com/articles/15545/obama-vs-romney-armenian-american-community-pressures-candidates-to-recognize-1915-genocide-by-ottoman-turkey).

36 The Armenian Weekly, Feb. 7, 2013.

37 Lewis Carroll, The Annotated Alice: The Definitive Edition, introduction and notes by Martin Gardner, New York: W. W. Norton, 2000, p. 213.

European Court Decision on Genocide Denial Strongly Condemned

PARIS, France (A.W.)—The Armenian National Committee office in France

and the European Armenian Federation for Justice and Democracy (EAFJD)

issued a joint statement today strongly condemning the Dec. 17 ruling of

the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) that the denial of the

Armenian genocide is not a criminal offense. According to the Court, the

2007 decision of the Lausanne Police Court against the head of Turkish

Workers’ Party Dogu Perincek is a violation of the right to freedom of

expression. (Read the Court’s press release here.)

The statement considered the ruling to be direct assistance to the wave of denial orchestrated by official Ankara and Baku throughout Europe. “Once again hiding behind the right to free speech, and following the example of the French Constitutional Council, the European Court undermines with this infamous decision the right to dignity of the victims and descendants of the Armenian genocide,” read the statement.

The statement further noted that the decision will “undoubtedly strengthen extremist movements” and undermine the voices calling for justice from within Turkey.

“Moreover, by declaring that ‘it would be very difficult to identify a general consensus’ on the Armenian genocide, the Court aligns itself with Perincek’s statement that the Armenian genocide is an ‘international lie.’ The Court’s approach that ‘clearly distinguished the present case from those concerning the negation of the crimes of the Holocaust’ is also deplorable. How can such a distinction be made by the highest human rights court in Europe?”

In conclusion, the statement noted that the ANC of France, in coordination with the EAFJD Brussels office, will fight against this unacceptable decision. “Switzerland has three months to appeal this verdict. We have requested a meeting with the Swiss Ambassador in Paris, to present our expectations from the Swiss authorities. Coordinated efforts will be made in other countries as well, through local ANCs and regional offices, as well as through official Yerevan, as we form a united front against this decision,” concluded the statement.

The statement considered the ruling to be direct assistance to the wave of denial orchestrated by official Ankara and Baku throughout Europe. “Once again hiding behind the right to free speech, and following the example of the French Constitutional Council, the European Court undermines with this infamous decision the right to dignity of the victims and descendants of the Armenian genocide,” read the statement.

The statement further noted that the decision will “undoubtedly strengthen extremist movements” and undermine the voices calling for justice from within Turkey.

“Moreover, by declaring that ‘it would be very difficult to identify a general consensus’ on the Armenian genocide, the Court aligns itself with Perincek’s statement that the Armenian genocide is an ‘international lie.’ The Court’s approach that ‘clearly distinguished the present case from those concerning the negation of the crimes of the Holocaust’ is also deplorable. How can such a distinction be made by the highest human rights court in Europe?”

In conclusion, the statement noted that the ANC of France, in coordination with the EAFJD Brussels office, will fight against this unacceptable decision. “Switzerland has three months to appeal this verdict. We have requested a meeting with the Swiss Ambassador in Paris, to present our expectations from the Swiss authorities. Coordinated efforts will be made in other countries as well, through local ANCs and regional offices, as well as through official Yerevan, as we form a united front against this decision,” concluded the statement.

Saturday, December 14, 2013

‘Cry Out’---struggling with un-forgiveness

Wednesday, December 4, 2013

‘Cry Out’

How God changed Norita Erickson’s ‘heart of stone’ and gave her a love for the Turkish people, especially those with disabilities

By Dan Wooding

Founder of ASSIST Ministries

SANTA ANA, CA (ANS) -- Southern California-born Norita Erickson of Kardelen Mercy Teams (www.kardelenmercyteams.org), based in Ankara, Turkey, where she works with Turkish people with disabilities, has an extraordinary story to tell.

She is from an Armenian background and during what was called the

“Armenian Genocide”, an estimated 1 and 1.5 million of her people were

slaughtered or exiled by Ottoman soldiers and mercenaries, so she had

every reason to not feel any warmth towards the Turks.

But, after struggling with un-forgiveness and unbelief for a

period in her life, she said that God changed her “heart of stone” and

gave her a deep love for the Turkish peoples and now she has lived there

since 1987 with her husband, Ken.

Norita, who was born in West Los Angeles to Armenian parents, she and her husband moved to Amsterdam, Holland, in 1979 to work with Youth With A Mission to Muslim refugees who had fled there to escape the problems in their home countries.

In an interview for my Front Page Radio program, she said, “While we were there, we had our hearts broken for all the people who moved to Western Europe from the Middle East and North Africa, and who had no clue or idea who Jesus was, or that He loved them or died for them. They included Berbers, Turks, Kurds, Iranians and Afghans.”

But really, the Turks were the last people on her mind during her time in Amsterdam, as the “Armenian Genocide” was still on her mind.

“All of my forefathers came from Cilicia, in the southern part of

Turkey,” she said. “There was an Armenian nation there for hundreds of

years and, in the latter half of the nineteenth century and early part

of the twentieth century, as the Ottoman Empire [sometimes referred to

as the Turkish Empire or simply Turkey], began to disintegrate, the

Turkish Christian minority was disseminated.

“It was the first known ethnic cleansing of the twentieth

century. Over a million and a half Armenians disappeared and were moved

out of their homes towns and villages and led to Northern Syria where,

today, we’re experiencing so much violence and evil. My grandfather was a

pastor who had been revived in the latter half of the nineteenth

century and he trained as a protestant minister and was a teacher.

“The Lord spoke to him in the early nineteen-hundreds -- 1914 or so -- and said, ‘You’re not going to die,’ and gave him a scripture from Psalm 119 that he took to mean that he would not die. However, he went through very many trials and tribulations, but it’s quite miraculous how he, and my family survived. All my great grandparents did not survive however.”

Why were the Armenians so hated?

Norita replied, “I believe that it was the political issue at the time

as there were Armenians who wanted to create their own nation state.

They were siding with foreign powers such as the British who had troops

in the disintegrating Ottoman Empire. So nationalism was on the move --

both Turkish, Russian and Armenian -- and it was an opportunity to wipe

these people out and therefore take their land.”

I then asked her what she and Ken discovered when they first arrived in Amsterdam.

“We had our hearts broken one Easter when we went to the national outdoor Easter celebration and discovered a man pouring over a little leaflet that had scripture and hymns in it. He looked puzzled, so we walked up to him and I asked him, ‘Do you know what this?’ and he said, ‘No’. He explained he was from Egypt and so we told that we were celebrating the resurrection of Jesus Christ. He then said, ‘Who’? And when we heard that we knew the Lord had was telling us that He wanted us to tell people like this Egyptian who Jesus is.

“We prayed, and sought the Lord about this, and the specific people group that we were to minister to, and shortly afterwards my husband came to me and said, ‘I believe God is calling us to the Turks’. And I said, ‘No, He’s not Ken. He could never call us to the Turks. They’re under a blood curse. They’ve never admitted to the genocide and they killed all my great grandparents. They’re scary people I could never go there.'

“But Ken would give up and said that we should keep on praying until we get on the ‘same page’. So we prayed and every day. I got on my knees cried out to God and I said, ‘Show my husband that he’s missed Your will and show him that he’s wrong’. But at the end of that month, he came back to me with a testimony that he’d heard of a Turk who had found new life in Jesus and who had stood up at a meeting in Germany and asked for forgiveness for what his people had done to the Armenians.

“And when I heard that testimony, God broke my heart. I began to weep

and I sensed the Lord speaking to me and say, ‘If I love them, how can

you not’? I knew that at that point I needed to cry tears of repentance

because I had put God in a little box. I had thought these people were

under a blood curse they could not be saved so I had reasoned why would

God call us to an impossible task? And instead the Lord showed me that

nothing is impossible with Him and He loved them. So I repented of my

hard heart and I asked him to give me a heart of forgiveness, and within

a very short time that’s what I got. I started to talk to Turkish

people in the city and just fell in love with them. I found that I had

so much in common with them. My upbringing in an Armenian-American home

had a lot that was in common with the Eastern culture of Turks.”

During their seven years with Youth With A Mission in Amsterdam,

the couple took a year off during that time to go to Turkey to learn the

language and the culture.

“We lived in a village and it was very difficult,” said Norita. “I got hepatitis and I had a baby. I thought this was a crazy thing I would never come back here. When we got back to Amsterdam, we could speak Turkish and then, we providentially met a fundamentalist Muslim who had found Christ, and I just happened to go to his workplace and found him.”

She said that he was working at a sewing machine and when he found that Norita was there, he felt he had to come and talk to her.

“He told me that he had ‘seen Jesus’ and that he had read the New Testament and, through that relationship that we developed, we learned about how village people understand Christ and the message of the Gospel.”

Then finally, in 1987, Norita told her husband that she was willing to

return to Turkey, and so with their, by now, two children, they moved to

Ankara, the capital city, where Ken got a job teaching in a school, and

she settled down to being a housewife.

“We started a Bible book store that we ran under the cover of a secular English language book store and we sold bibles in all kinds of languages in an upscale mall. And all during this time from year to year seeking the Lord on where we should go from here,” she said. It wasn’t long before Norita discovered what God had planned for her -- and that was to help the disabled people of the area where they lived.

“I discovered that in that entire region, not just in Turkey, but throughout the Middle East, North Africa, all the way up through Central Asia, that if you’re born with a disability or you end up with a disability through an accident or sickness, you are considered cursed,” she said. “Children are thrown away, hidden away, because the families are afraid that they'll be identified and stigmatized as cursed. And if you’re cursed nobody wants to marry your children and if you’re cursed you’re the rejected you’re the pariahs of society.

“Turkey is a country of 75,000,000 people and 99% of the population is Islamic, some more strongly Islamic, while others are more moderate. But 17% of the Turkish population and that might include some Christian minorities too, has a disability. That’s a very high percentage. Part of it is also a belief in fate. In many Islamic countries, they believe that God has written your whole life on your forehead and nothing you can do will change it. So you don’t mess with fate because that’s what God has given you as the test for your life. We have discovered that that tends to be the case.

Soon, she said, her husband changed jobs and began making “appropriate technology wheelchairs.”

Norita went on to say, “My husband was busy doing this, but I had no

interest as I was doing other things. I really didn’t understand what it

meant to serve the disabled until 1997 when I went into a state-run

institution and was shocked to find 400 children who had been sent away

to live in this place. They were tied in their beds, covered in their

vomit and bodily filth, and were screaming, as there did appear to be

anyone there to care for them. No one appeared to know what to do with

them and the attitude of the care givers was that these children were

‘cursed’ and they were ‘cursed’ having to work in such a place and so

they would just do a little as was needed until they died.

“I was shocked and I ran out of that place and I cried out to

God. I was angry. I said, ‘How could You show this to me? I wish I

didn’t know what I just saw’. It was overwhelming – just like going into

a concentration camp. The Lord didn’t answer me at that point. But two

weeks later, I got sick and I was up in the middle of the might praying;

moaning and groaning, saying, ‘I wish my mom were here to look after me

and make me some chicken soup. Then, all of a sudden, I became

enveloped in a black cloud of isolation. I felt so lonely. I started to

cry and I heard the Holy Spirit saying, ‘You are weeping my tears for

these children.’

“And all of a sudden, I had a vision of a garden with trees and animals and flowers and children sitting up and some standing up and there were some adults there, laughing and enjoying the sunlight. The Lord spoke to me and said, ‘I want you to do that.’ I was confused and told Him that I didn’t know anything about helping disabled kids and I was just a Bible teacher and child worker. However, the Lord convinced me that He was in this, so within a very few days, I called another of my Turkish friends who knew Jesus and asked this friend if they would come out to the institution and said, ‘God has got something in mind for us out at this institution. So that was the inception of Kardelen Mercy Teams.”

Norita explained that Kardelen is the Turkish word for a snowdrop flower and they are the first flower to emerge at the end of winter when they respond to sunlight.

“I saw these children, and our ministry, like this. These children are hidden away, but they respond to the sunlight of God’s love as we bring it into their homes and into these institutions,” she said.

“From 1997, we worked for 12 years as volunteers in the state run institution and we went in five days a week, from nine to five, and during that time, we brought in over a million dollars’ worth of goods and services to these neglected children.

“Our view was that we loved everybody there and modeled God’s heart for every human being, and in that process, several of the physically handicapped young people came to the Lord. Many of them are with the Lord today. Some of them I got out of the institution and are now part of my staff in Ankara, and we're working in another two places with care providers.

“Then, four years ago, we moved out of the institution and into the community. We now have Kardelen Mercy Teams and our brief is to go to the families who were most likely to send their children away to an institution. We learned in the very beginning of our ministry that there was a waiting list of 3,000 families to get their kids into that hell-hole, and we decided to go the families and love on them and show them they can work with their kids and show them that they are not cursed. So that is what we do now.”

Norita said that one of the ways they do this is through birthday parties.

“We tell them that it is good that they have been born and we share with the parents that they are blessed to have such children,” she said. “In so doing, we break the stigma on them, as they often do not have any relationship with their neighbors because they're considered cursed. When we come in with balloons and a cake and do all kinds of fun things, and also bring along a specially-designed wheelchair for the child, and we also bring diapers or food packages, and in the winter, we also bring coal to heat their homes.

“When we provided these things, we see that people are changed. They

respond to us because we pray and we sing the Lord’s Prayer over them.

These are all Muslim people, but they have a heart beating and they have

a need to know the Lord just like anybody else.”

Norita then revealed that she has just released a book about the

first 12 years of their ministry called “Cry Out,” which, she said,

“features the lessons that God showed us, the miracles He performed, and

the opposition we experienced.”

To find out more about the book and the ministry, just go to www.kardelenmercyteams.com and to listen to the radio interview, please go to www.assist-ministries.com/FrontPageRadio/FPR12.1.1NoritaEricksonMono.mp3

Note: I would like to thank Robin Frost for transcribing this interview

‘Cry Out’

How God changed Norita Erickson’s ‘heart of stone’ and gave her a love for the Turkish people, especially those with disabilities

By Dan Wooding

Founder of ASSIST Ministries

SANTA ANA, CA (ANS) -- Southern California-born Norita Erickson of Kardelen Mercy Teams (www.kardelenmercyteams.org), based in Ankara, Turkey, where she works with Turkish people with disabilities, has an extraordinary story to tell.

|

|

Norita Erickson, Founder and Director of Kardelen Mercy Teams

|

Norita, who was born in West Los Angeles to Armenian parents, she and her husband moved to Amsterdam, Holland, in 1979 to work with Youth With A Mission to Muslim refugees who had fled there to escape the problems in their home countries.

In an interview for my Front Page Radio program, she said, “While we were there, we had our hearts broken for all the people who moved to Western Europe from the Middle East and North Africa, and who had no clue or idea who Jesus was, or that He loved them or died for them. They included Berbers, Turks, Kurds, Iranians and Afghans.”

But really, the Turks were the last people on her mind during her time in Amsterdam, as the “Armenian Genocide” was still on her mind.

|

|

Kardelen’s

Care Team visits this mom and her two children on a monthly basis. Her

estranged husband every now and then shows up, and after one unpleasant

visit, she became pregnant with this little boy

|

“The Lord spoke to him in the early nineteen-hundreds -- 1914 or so -- and said, ‘You’re not going to die,’ and gave him a scripture from Psalm 119 that he took to mean that he would not die. However, he went through very many trials and tribulations, but it’s quite miraculous how he, and my family survived. All my great grandparents did not survive however.”

Why were the Armenians so hated?

|

|

Single-mom

Daria takes Ekeem outside for a walk. Ekeem suffers from Cerebral

Palsy, and since having his chair, he is able to breath, eat and

function better

|

“We had our hearts broken one Easter when we went to the national outdoor Easter celebration and discovered a man pouring over a little leaflet that had scripture and hymns in it. He looked puzzled, so we walked up to him and I asked him, ‘Do you know what this?’ and he said, ‘No’. He explained he was from Egypt and so we told that we were celebrating the resurrection of Jesus Christ. He then said, ‘Who’? And when we heard that we knew the Lord had was telling us that He wanted us to tell people like this Egyptian who Jesus is.

“We prayed, and sought the Lord about this, and the specific people group that we were to minister to, and shortly afterwards my husband came to me and said, ‘I believe God is calling us to the Turks’. And I said, ‘No, He’s not Ken. He could never call us to the Turks. They’re under a blood curse. They’ve never admitted to the genocide and they killed all my great grandparents. They’re scary people I could never go there.'

“But Ken would give up and said that we should keep on praying until we get on the ‘same page’. So we prayed and every day. I got on my knees cried out to God and I said, ‘Show my husband that he’s missed Your will and show him that he’s wrong’. But at the end of that month, he came back to me with a testimony that he’d heard of a Turk who had found new life in Jesus and who had stood up at a meeting in Germany and asked for forgiveness for what his people had done to the Armenians.

|

|

A

mission team from the U.S. sponsored a picnic in a nearby park for those

we serve. It was a full day that included a barbecue, games, wheelchair

donations and a birthday cake

|

“We lived in a village and it was very difficult,” said Norita. “I got hepatitis and I had a baby. I thought this was a crazy thing I would never come back here. When we got back to Amsterdam, we could speak Turkish and then, we providentially met a fundamentalist Muslim who had found Christ, and I just happened to go to his workplace and found him.”

She said that he was working at a sewing machine and when he found that Norita was there, he felt he had to come and talk to her.

“He told me that he had ‘seen Jesus’ and that he had read the New Testament and, through that relationship that we developed, we learned about how village people understand Christ and the message of the Gospel.”

|

|

Dr.

S is a volunteer physical therapist who assists with the “Wheelchair

For a Child” program. He is with Ayshe, who received a chair in July of

2013

|

“We started a Bible book store that we ran under the cover of a secular English language book store and we sold bibles in all kinds of languages in an upscale mall. And all during this time from year to year seeking the Lord on where we should go from here,” she said. It wasn’t long before Norita discovered what God had planned for her -- and that was to help the disabled people of the area where they lived.

“I discovered that in that entire region, not just in Turkey, but throughout the Middle East, North Africa, all the way up through Central Asia, that if you’re born with a disability or you end up with a disability through an accident or sickness, you are considered cursed,” she said. “Children are thrown away, hidden away, because the families are afraid that they'll be identified and stigmatized as cursed. And if you’re cursed nobody wants to marry your children and if you’re cursed you’re the rejected you’re the pariahs of society.

“Turkey is a country of 75,000,000 people and 99% of the population is Islamic, some more strongly Islamic, while others are more moderate. But 17% of the Turkish population and that might include some Christian minorities too, has a disability. That’s a very high percentage. Part of it is also a belief in fate. In many Islamic countries, they believe that God has written your whole life on your forehead and nothing you can do will change it. So you don’t mess with fate because that’s what God has given you as the test for your life. We have discovered that that tends to be the case.

Soon, she said, her husband changed jobs and began making “appropriate technology wheelchairs.”

|

|

|

A

Care Team member takes Mehmet out for a walk. Before Mehmet received his

chair, he spent most of his day on the hard cement floor of the

family's two-room hovel, unable to get outside

|

“And all of a sudden, I had a vision of a garden with trees and animals and flowers and children sitting up and some standing up and there were some adults there, laughing and enjoying the sunlight. The Lord spoke to me and said, ‘I want you to do that.’ I was confused and told Him that I didn’t know anything about helping disabled kids and I was just a Bible teacher and child worker. However, the Lord convinced me that He was in this, so within a very few days, I called another of my Turkish friends who knew Jesus and asked this friend if they would come out to the institution and said, ‘God has got something in mind for us out at this institution. So that was the inception of Kardelen Mercy Teams.”

Norita explained that Kardelen is the Turkish word for a snowdrop flower and they are the first flower to emerge at the end of winter when they respond to sunlight.

“I saw these children, and our ministry, like this. These children are hidden away, but they respond to the sunlight of God’s love as we bring it into their homes and into these institutions,” she said.

“From 1997, we worked for 12 years as volunteers in the state run institution and we went in five days a week, from nine to five, and during that time, we brought in over a million dollars’ worth of goods and services to these neglected children.

“Our view was that we loved everybody there and modeled God’s heart for every human being, and in that process, several of the physically handicapped young people came to the Lord. Many of them are with the Lord today. Some of them I got out of the institution and are now part of my staff in Ankara, and we're working in another two places with care providers.