click for more

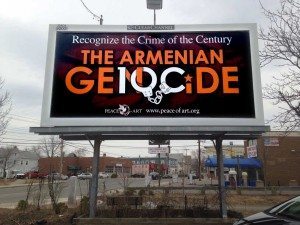

Impressions from the Armenian Genocide commemoration in Istanbul

Ninety-nine years ago in the wee spring hours, Ottoman-era policemen

marched through the streets of old Constantinople. Over the course of

that fateful night, and the weeks that followed, they arrested and

deported the most prominent Armenian writers, poets, journalists,

intellectuals and men who lived by the pen from the Golden age of the

Armenian intelligentsia in old Constantinople. These men were taken to

the Haydarpasha train station and shipped deep into the interior of

Ottoman Turkey where they were jailed and murdered.

Only a few survived, among them the iconic Komitas Vartabed, the

priest, composer and musicologist who became mute and descended into

madness as a result of the horrors he witnessed during the Armenian

Genocide.

Komitas’s ancient musical soul went silent and today, 99 years later,

I sat on the wet asphalt in the heart of Istanbul listening to his

otherworldly voice recorded once upon a time in the early 20th century.

It was crackling and booming on multiple loudspeakers among Armenians,

Turks and Kurds gathered and jam-packed like sardines to honor the

Armenian martyrs and to call what happened here in this country by its

rightful name—Genocide. Young, old, middle-aged, natives and

diasporans…we all sat side-by-side humming with Komitas, Dle Yaman and Der Voghormya.

Youth and elders held up laminated color and black-and-white

photocopies of Krikor Zohrab, Siamanto, Diran Kelekian, Daniel Varoujan

and several Ottoman-era Armenians who lived by the pen and were cut down

by the swords. Their eyes gazed out from the photocopies at this new,

small and fearless generation of Turks and Armenians committed to

keeping the flame and voice of memory alive through the act of solemnity

and presence together as a unified voice.

This is a brave and vocal minority that has chosen to not be silent.

Middle-aged women wept openly. Members of the New Zartonk stood

steadfast with printed banners. All gathered had managed through

solidarity and sheer will to silence the filet mignon of Bolis real

estate where millions pass through on a daily basis.

The press swarmed all over the street, perched on the roofs of

businesses and establishments that demonstrated great respect to the

commemorators by allowing the photojournalists to lean out of their

windows and second-story patios immortalizing this brief hour on this

very busy Spring day where the spirits of our one and a half-million

dead were prayed for. Next year, this generation will return again and

again and again.

While the speechwriters and politicos continue to conjure new ways to

manipulate verbs and adjectives to avoid the truth of the Genocide,

this new generation will be burning the midnight oil printing out the

laminated images of the martyrs.

This small victory is a symbolic one that would have been

unimaginable before. However small, its echoes are being heard now very

loud and clearly across the world thanks to the point, shoot, save and

upload settings in our garden variety of smart phones. And today’s

presence and solidarity, like Komitas’s voice, will not be silenced.

Today, I began to grasp the meaning of the word “vicdan” which means

“conscience” in Turkish.

These young university students and Istanbul natives were here out of

duty and a calling sitting on the damp asphalt holding vigil. They were

here because they cared. Who would have thought that in 2014 we would

hear the ear-shattering boom of Der Voghormya in the

ground-zero of Istanbul? That is not to say things here are where they

should be. Far from it but each small symbolic step here is a step

forward.

After the end of the commemoration, I was handed a red carnation.

With Komitas’s voice lingering in my ears, I felt a certain temporary

peace gnawed by the begrudging reminder that we would never be able to

grasp the complete magnitude of what happened during the Genocide. Yet,

we will continue to hold candles to collective and personal memory and

through voice, song, image, solidarity and creative outpouring honor and

demand justice for what will continue to dwarf our imaginations for

generations to come

The Four Shades of Turkey, and the Armenians

Like a cell dividing itself into two, then each new cell

further dividing into two, Turkey keeps being divided. Although

divisions always existed, they remained mostly suppressed, until now. In

this article, I will outline the old and new divisions in Turkey, and

the Turks’ perception of us Armenians.

Beginning in 1923 with the founding of the republic, Turkey was governed by a secular, Kemalist and nationalist ideology, with the single-minded objective of creating and maintaining a monolithic, single-nation state. Regardless of which party was in power, leftist or rightist, the “deep state”—dominated by the armed forces, big business, big state bureaucracy, media, and academia—directed all the affairs behind the scenes. The “deep state” leaders and their backers emerged as the elite of the society, aptly named the nationalist White Turks; they inherited and developed a state built on the economic foundations of plundered and confiscated Armenian and Greek wealth. The masses in Anatolia were mainly utilized as free bodies for the military elite, or as cheap labor for the industrial elite, and remembered only at election time. White Turks looked down to pious Sunni Muslim majority and labeled them takunyali, or clog wearers. The disappearance of the Armenians and Greeks from these lands was fiercely denied. The existence of other ethnic people in Turkey, such as the Kurds, was also continuously denied. Turkey is only for Turks, was their motto. As the Armenians and Greeks were already wiped out, the other ethnic groups were told that they were now Turks, or else.

The supremacy of the White Turks ended in 2003 with the election of Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his moderately Islamic party. Despite attempts by the “deep state” to topple him, Erdogan outmaneuvered the White Turks, thanks to the religious Sunni Muslims of Anatolia and the recent arrival of underprivileged masses from Anatolia to the big cities. The provincial and religious Turks quickly secured and strengthened their grip on power. The influential fundamentalist religious leader Fethullah Gulen, who had been forced to leave Turkey during the previous regimes, cooperated with Erdogan and his followers quickly filled the cadres of bureaucracy, including key posts in the police, security, judiciary, and academic fields. Hundreds of “deep state” leaders and elite White Turks in the military, media, and academia were arrested and jailed on charges of an attempted coup d’état against the government. Many White Turks began to leave the country. Although less intolerant toward minorities than the White Turks, the attitude of the new leaders toward minorities and the Kurds did not change much.

The alliance between Erdogan and Gulen ended in late 2013, when Erdogan felt secure enough to discard Gulen, and shut down the numerous supplementary educational facilities he controlled. Many parents in Turkey depended on these facilities for the child’s advancement, as the state education system is not sufficient to secure admission to the state universities. These facilities were used as a powerbase by Gulen; they were a major source of income and facilitated recruitment of new followers. Soon after Erdogan announced his intention to close these facilities, state prosecutors and police controlled by Gulen revealed they had uncovered a major corruption scandal involving four of Erdogan’s ministers and hundreds of millions of dollars in bribes. The scandal was replete with juicy details of money-counting machines and millions stashed in shoeboxes in the ministers’ homes. Erdogan counter-attacked by swiftly removing, replacing, and firing thousands of state prosecutors, judges, and police officers deemed to be followers of the Gulen movement. In the last few weeks, at least 10 taped telephone conversations involving Erdogan himself have been leaked. In them, Erdogan directs his son to dispose of hundreds of millions of cash in euros and dollars from their homes; orders several businessmen to pay $100 million each toward buying a media empire that he wants controlled; demands another media owner to fire several journalists; and decides how much certain contractors must pay in return for large contracts.

In the Western world, even a hint of attempted bribery or corruption is sufficient in bringing down governments. But in Turkey, Erdogan carries on, dismissing the evidence as plots hatched by his one-time ally (and now mortal enemy) Gulen, as well as other virtual enemies, such as “parallel states” within Turkey, and, predictably, external enemies such as Israel, the U.S., the European Union, and the “interest lobby,” all jealous of Turkey’s fast growth. Erdogan’s latest move is to try to win back the nationalists who were charged and jailed for attempting to topple his own government; as a result, most of the jailed “deep state” leaders have been released, including the former army chief of staff and other commanders; one of the masterminds of the Hrant Dink assassination; the racist lawyer who hounded Hrant Dink for “insulting Turkishness”; the politician who was charged for stating “The Armenian Genocide is a lie” in Switzerland, and with whom the European Court of Human Rights recently sided in the name of freedom of speech; an organized crime leader who arranged several contract killings of anti-nationalists and Kurds; the murderers of a German and two Turkish Protestant missionaries in Malatya; and several other ultra nationalist/racist intellectuals and journalists.

While these divisions have emerged among the Turks of Turkey, the Kurds of Turkey have made major advances toward greater autonomy, language rights, and self-determination—a struggle that began in the 1980’s as a guerilla movement and, more recently in the 2000s, has become a political movement. The imprisoned PKK leader Abdullah Ocalan imposed his will on Erdogan, who conceded to peace talks in exchange for a ceasefire.

Even though the four major divisions within Turkey—the “deep state,” the Erdogan people, the Gulen people, and the Kurds—keep fighting and plotting against one another, they come together and close ranks when it comes to the Armenian issue, past and present. The Turks themselves categorize Armenians into three distinct groups (in a completely misguided manner): the Good, the Bad, and the Poor. The small Armenian community in Turkey is the Good, as it is easily controllable and no longer a threat, possessing neighborly memories of shared dolma or topik. They’re Good, that is, as long as they don’t ask much about the past or present, like Hrant Dink dared to. The Armenian Diaspora is the Bad, with its evil presence in every country poisoning locals against Turks and Turkey, and spreading lies about the “alleged” genocide of 1915. Finally, the Armenians who recently left Armenia to come to Turkey to find bread are the Poor. The Kurds, on the other hand, have more empathy toward the Armenians; however, it is mainly because “the enemy of my enemy is my friend.” Although Ocalan came close to acknowledging the genocide, he has empathy only for the Good Armenians in Turkey and continues to define the diaspora as part of the external lobby threat against both Turks and Kurds. While the Kurds (barring a few exceptions) acknowledge the sufferings of the Armenians in 1915, they cannot bring themselves to acknowledge the active role they played in the genocide, nor open the subject of returning the vast properties seized from the Armenians.

Those Armenians who believe in meaningful dialogue with the peoples of Turkey now face the additional challenge of choosing one or more of these groups at the risk of alienating the others. The prospect of any productive result, however, becomes dimmer by the day. Nevertheless, dialogue does continue, with the involvement of civil society organizations and intellectuals, and more significantly through the emerging force of Islamized Armenians of Turkey. Dialogue must and will continue until all four groups start to see that all Armenians, whether in Turkey, the diaspora, or Armenia—and whether good, bad, or poor—were all equally impacted by the genocide and equally demand acknowledgment and restitution.

Beginning in 1923 with the founding of the republic, Turkey was governed by a secular, Kemalist and nationalist ideology, with the single-minded objective of creating and maintaining a monolithic, single-nation state. Regardless of which party was in power, leftist or rightist, the “deep state”—dominated by the armed forces, big business, big state bureaucracy, media, and academia—directed all the affairs behind the scenes. The “deep state” leaders and their backers emerged as the elite of the society, aptly named the nationalist White Turks; they inherited and developed a state built on the economic foundations of plundered and confiscated Armenian and Greek wealth. The masses in Anatolia were mainly utilized as free bodies for the military elite, or as cheap labor for the industrial elite, and remembered only at election time. White Turks looked down to pious Sunni Muslim majority and labeled them takunyali, or clog wearers. The disappearance of the Armenians and Greeks from these lands was fiercely denied. The existence of other ethnic people in Turkey, such as the Kurds, was also continuously denied. Turkey is only for Turks, was their motto. As the Armenians and Greeks were already wiped out, the other ethnic groups were told that they were now Turks, or else.

The supremacy of the White Turks ended in 2003 with the election of Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his moderately Islamic party. Despite attempts by the “deep state” to topple him, Erdogan outmaneuvered the White Turks, thanks to the religious Sunni Muslims of Anatolia and the recent arrival of underprivileged masses from Anatolia to the big cities. The provincial and religious Turks quickly secured and strengthened their grip on power. The influential fundamentalist religious leader Fethullah Gulen, who had been forced to leave Turkey during the previous regimes, cooperated with Erdogan and his followers quickly filled the cadres of bureaucracy, including key posts in the police, security, judiciary, and academic fields. Hundreds of “deep state” leaders and elite White Turks in the military, media, and academia were arrested and jailed on charges of an attempted coup d’état against the government. Many White Turks began to leave the country. Although less intolerant toward minorities than the White Turks, the attitude of the new leaders toward minorities and the Kurds did not change much.

The alliance between Erdogan and Gulen ended in late 2013, when Erdogan felt secure enough to discard Gulen, and shut down the numerous supplementary educational facilities he controlled. Many parents in Turkey depended on these facilities for the child’s advancement, as the state education system is not sufficient to secure admission to the state universities. These facilities were used as a powerbase by Gulen; they were a major source of income and facilitated recruitment of new followers. Soon after Erdogan announced his intention to close these facilities, state prosecutors and police controlled by Gulen revealed they had uncovered a major corruption scandal involving four of Erdogan’s ministers and hundreds of millions of dollars in bribes. The scandal was replete with juicy details of money-counting machines and millions stashed in shoeboxes in the ministers’ homes. Erdogan counter-attacked by swiftly removing, replacing, and firing thousands of state prosecutors, judges, and police officers deemed to be followers of the Gulen movement. In the last few weeks, at least 10 taped telephone conversations involving Erdogan himself have been leaked. In them, Erdogan directs his son to dispose of hundreds of millions of cash in euros and dollars from their homes; orders several businessmen to pay $100 million each toward buying a media empire that he wants controlled; demands another media owner to fire several journalists; and decides how much certain contractors must pay in return for large contracts.

In the Western world, even a hint of attempted bribery or corruption is sufficient in bringing down governments. But in Turkey, Erdogan carries on, dismissing the evidence as plots hatched by his one-time ally (and now mortal enemy) Gulen, as well as other virtual enemies, such as “parallel states” within Turkey, and, predictably, external enemies such as Israel, the U.S., the European Union, and the “interest lobby,” all jealous of Turkey’s fast growth. Erdogan’s latest move is to try to win back the nationalists who were charged and jailed for attempting to topple his own government; as a result, most of the jailed “deep state” leaders have been released, including the former army chief of staff and other commanders; one of the masterminds of the Hrant Dink assassination; the racist lawyer who hounded Hrant Dink for “insulting Turkishness”; the politician who was charged for stating “The Armenian Genocide is a lie” in Switzerland, and with whom the European Court of Human Rights recently sided in the name of freedom of speech; an organized crime leader who arranged several contract killings of anti-nationalists and Kurds; the murderers of a German and two Turkish Protestant missionaries in Malatya; and several other ultra nationalist/racist intellectuals and journalists.

While these divisions have emerged among the Turks of Turkey, the Kurds of Turkey have made major advances toward greater autonomy, language rights, and self-determination—a struggle that began in the 1980’s as a guerilla movement and, more recently in the 2000s, has become a political movement. The imprisoned PKK leader Abdullah Ocalan imposed his will on Erdogan, who conceded to peace talks in exchange for a ceasefire.

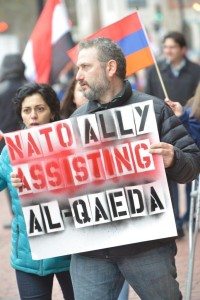

Even though the four major divisions within Turkey—the “deep state,” the Erdogan people, the Gulen people, and the Kurds—keep fighting and plotting against one another, they come together and close ranks when it comes to the Armenian issue, past and present. The Turks themselves categorize Armenians into three distinct groups (in a completely misguided manner): the Good, the Bad, and the Poor. The small Armenian community in Turkey is the Good, as it is easily controllable and no longer a threat, possessing neighborly memories of shared dolma or topik. They’re Good, that is, as long as they don’t ask much about the past or present, like Hrant Dink dared to. The Armenian Diaspora is the Bad, with its evil presence in every country poisoning locals against Turks and Turkey, and spreading lies about the “alleged” genocide of 1915. Finally, the Armenians who recently left Armenia to come to Turkey to find bread are the Poor. The Kurds, on the other hand, have more empathy toward the Armenians; however, it is mainly because “the enemy of my enemy is my friend.” Although Ocalan came close to acknowledging the genocide, he has empathy only for the Good Armenians in Turkey and continues to define the diaspora as part of the external lobby threat against both Turks and Kurds. While the Kurds (barring a few exceptions) acknowledge the sufferings of the Armenians in 1915, they cannot bring themselves to acknowledge the active role they played in the genocide, nor open the subject of returning the vast properties seized from the Armenians.

Those Armenians who believe in meaningful dialogue with the peoples of Turkey now face the additional challenge of choosing one or more of these groups at the risk of alienating the others. The prospect of any productive result, however, becomes dimmer by the day. Nevertheless, dialogue does continue, with the involvement of civil society organizations and intellectuals, and more significantly through the emerging force of Islamized Armenians of Turkey. Dialogue must and will continue until all four groups start to see that all Armenians, whether in Turkey, the diaspora, or Armenia—and whether good, bad, or poor—were all equally impacted by the genocide and equally demand acknowledgment and restitution.