This

paper is an expansion of remarks given by the author at McGill

University and the University of Toronto on March 18 and 20, 2015,

respectively.

There is an oft-repeated false truism about genocide, that denial is

the final stage of genocide. It is so unquestionably accepted that it

has even made its way into formal stage-theories of genocide. It is,

unfortunately, quite wrong. Denial is not the final stage of genocide,

but rather present throughout most of the genocidal process. When they

are doing it, perpetrators almost inevitably deny that what they are

doing is genocide. For instance, Talaat and his cronies were adamant

that their violence against Armenians was not one-sided mass

extermination, but instead a response to Armenian rebellion and violent

perfidy in Van and elsewhere. They maintained that the deportations were

intended to move Armenians to other areas of the empire, not a means of

destroying the Armenian population of village after village, town after

town.

The sky above the Armenian Cemetery of Diyarbakir (Photo: Scout Tufankjian)

We see variations on this theme in case after case. The United States

did not hunt down Native American groups, did not kill those under

their control or force them onto destructive reservations; no, my

country fought the so-called “savages” in a series of “Indian Wars.”

(One need only look at the historical record of hyper-violence by the

U.S. military and general population, which tortured, raped, killed, and

then mutilated Native Americans, to see who the real savages have

been.) The Tasmanians were killing livestock and even settlers, while

the Herero were in revolt. The Jews had a world conspiracy that was out

to get decent Aryans and needed to be stopped by the most brutal means

possible. Pro-democracy activists in Indonesia were actually a communist

insurgency, while Guatemalan Mayans, who appear to have been

hardworking people in dire poverty just trying to survive the assaults

on them by their government and country’s wealthy elite, were actually

communists determined to destroy the good values of their society and

impose a horrible political and social order. The Tutsi were hell-bent

on dominating the Hutu, who had no choice but to respond, and the

Bosnians Muslims, not Serbs were the aggressors, despite the fact that

the latter had by far more military power. Today, the supposed rebellion

in the Nuba Mountain and Blue Nile regions of Sudan leave “statesman”

Omar al-Bashir no choice but to bomb thousands of civilians with Antonov

aircraft.

Denial is not a stage of genocide, but part of the commission of

genocide, especially as prosecutions have led sophisticated perpetrators

to begin their international tribunal defenses while the blood is still

flowing.

Denial is not a stage of genocide, but part of the

commission of genocide, especially as prosecutions have led

sophisticated perpetrators to begin their international tribunal

defenses while the blood is still flowing.

Denial is certainly prevalent after genocide, as the false truism

does capture correctly. It is not a final stage, however. Indeed, as

long as denial persists, we can be sure that the genocidal process is

still operating. Denial accompanies this operation, and furthers its

goals of “eliminating the consequences” of the genocide for the

perpetrator group, even generations and centuries after the violence and

destruction. Denial is not the final stage of genocide; consolidation

of the genocide is.

1 A genocide is consolidated after the

phase of direct destruction—sometimes long after—when the perpetrator

group has made final and irrevocable all the various demographic,

political, identity, military, cultural, financial, territorial, and

other material and symbolic gains achieved through and deriving from the

genocide, when the post-genocide state of affairs has become

completely, utterly, and irremediably rendered permanent so that,

whether the victim group has faded out of existence or still somehow

persists, its condition will remain as it is, in the enduring position

of victimhood unredeemed and unrepaired. Denial, geopolitically

motivated treaties, and other influences all conspire with the passage

of time in the process of consolidation. What is striking about

consolidation is that, no matter to what extent complex forces can be

blamed for the direct phase of a genocide and leave room for repentance

by the perpetrator group, consolidation is done with a full

understanding of what was done through a genocide and the moral

obligation to repair that it has imposed, and in deliberate rejection by

the perpetrator group of somehow doing right by the victims.

A genocide deeply ruptures the pre-existing status quo and in

particular devastates the victim community. Just because the violence

and destruction of a genocide end does not mean that their consequences

are mitigated. On the contrary, so long as the impact of a genocide on

its victims remains unrepaired, that impact continues devastating them

in perpetuity. Despite the wishful thinking of philosophers such as

Jeremy Waldron, as Jermaine McCalpin has emphasized,

2 time

does not heal the wounds of genocide. On the contrary, as generation

follows generation, more and more people are injured, demeaned, and

assaulted by the original violence. With each day that passes without

repair, the scope of the destruction increases. The end limit point of

this process is not successful denial, but the point at which denial no

longer is necessary because the genocide’s impact has become fully

irreparable, as the genocide’s consequences become everlastingly secured

in the global social, political, and economic status quo. Denial ends

not with the success of denial, but the total and complete consolidation

of genocide. Genocides are denied because their effects—both material

and in terms of historical memory—are, thankfully, still contested.

Consolidation can happen through denial, at the point where denial has

erased the genocide completely enough that it will never rate

contemporary political and legal consideration, but it can also occur

when the genocide is fully known yet considered so far removed from

present concerns that its results are generally accepted.

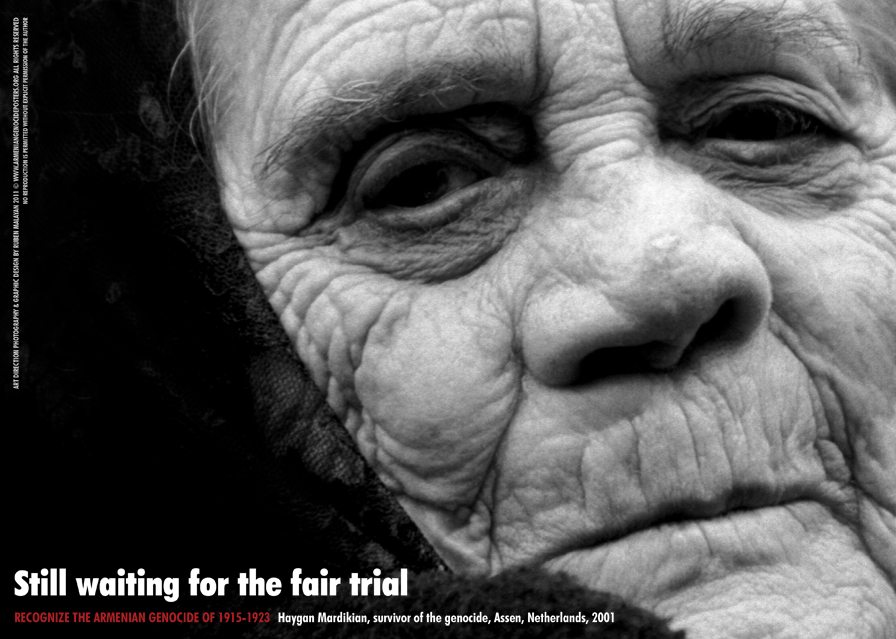

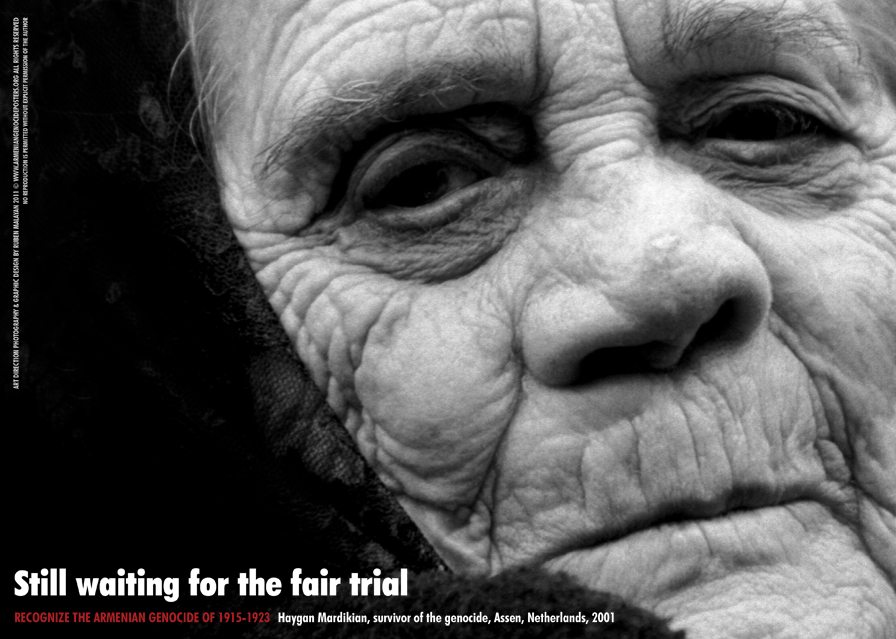

‘Still waiting for the fair trial’ (Design and photo: Ruben Malayan)

This is evident through a few examples. The genocides of the Herero,

Australian Aborigines, Native Canadians, and Native Americans are still

denied actively, precisely because the victim groups still experience

the impacts of the injuries of direct massacre, religious and cultural

destruction, internment on reservations, family degradation through

boarding schools and other forced transfers of children from their home

groups, and more, and so a reparative process could actually address

these harms. Denial stops reparations. Denial of the Holocaust continues

because the evils of anti-Semitism that it maximized horrifically

remain vibrant forces in human society across the globe; the Holocaust

persists through its legacy of making Jews, already considered fit

targets of oppression and violence, the fit targets of mass

extermination. Denials of the Bangladesh, East Timor, Cambodian, and

other cases continue because perpetrators and survivors yet live, and

the deep harm done to each society remains largely unaddressed. The list

of denied genocides goes on.

No one denies the genocides of Melos and Carthage, of the Cathars or

by Chengis Khan, because the destruction they imparted into the world

has long since been completely and irreparably incorporated into the

world order. For these and all too many other genocides, utterly and

completely “getting away with it” has been the final stage. How many

so-called great societies and states celebrated in the present and past

are so because of their complete success in consolidating the genocides

they committed?

The false truism reflects an important effect of denial. Years of

denial after a genocide actually skew the framework through which that

genocide is perceived and understood. Faced with a strong denial

campaign, survivors and concerned others, including in the perpetrator

group, find themselves in a seemingly endless, disheartening, degrading,

and exhausting struggle simply to get the truth recognized by enough

people that it will not be erased from the annals of human history. Soon

enough, the genocide itself is lost in the struggle against denial: The

struggle against denial becomes an end in itself. The defeat of denial

under such circumstances comes to be seen as justice for the genocide.

With this, defeated or not, denial wins the day, by preventing a victim

group from seeing that the defeat of denial does not give it justice,

but merely gets it back to the starting point from which a justice

process can finally be initiated. For long-past genocides, victim groups

and others forget that recognition of the genocide against denial does

not repair the harms done by the genocide, but merely addresses the

secondary problem of denial. Only by directly and substantially engaging

those harms through a comprehensive reparations process can the world

do what it can to bring justice to the victim group and all of humanity.

3

The recent attention on reparations for the Armenian case represents

an important move beyond focus on denial. With this in mind, it is clear

that 2015, the 100

th anniversary, should not be understood

as a culminating point in the post-genocide history of the Ottoman

Genocide of Christian Minority Groups. If recognition comes this year,

as it could—though I am not holding my breath—it will mean only that

finally, after a century, the victim groups and others concerned with

human rights can finally start addressing the harms done. But the

effects of genocide are not measured in such neat little packages of 10

years, 50 years, or 100 years, which we make special, after all, simply

because of the evolutionary accident that has given us 10 fingers to

count with. As much as some people, especially those outside of victim

communities who need a good story before they are willing to care about a

legacy of mass violence, attach significance to such time intervals,

the consequences of genocide play out in a complex history of material

and social causal chains so that no particular year or date has any

great actual meaning. Or, to put it more correctly,

every year and, indeed,

every day

in the long aftermath of a genocide have great importance, until the

injuries are addressed in a substantial way that is appropriately

transformative for both the victim and perpetrator groups.

Cover of the AGRSG Report on Reparations

Helping to accomplish this shift in focus toward repair has been the

Armenian Genocide Reparations Study Group (AGRSG), which in 2007 I

formed with renowned international lawyer and legal scholar Alfred de

Zayas, former Armenian Ambassador to Canada and treaty expert Ara

Papian, and dynamic Jamaican political scientist Jermaine McCalpin. The

AGRSG has done a comprehensive study of reparations for the Armenian

Genocide. The AGRSG Final Report

4 analyzes the harms done and

the legal, historical, and ethical justifications for repair, and then

proposes an innovative transitional justice process to effect it. The

report includes determinations of territorial and other restitution that

should be made by Turkey and discussion of the ways in which

reparations should be used by the Armenian group as a whole to ensure

the future viability of its state and its global identity.

The harms done by the Armenian Genocide are very much present today.

They include the dramatic demographic impact on the Armenian population

through direct and indirect killing as well as forced assimilation that

reduced the Armenian population of the Ottoman Empire to less than 40

percent of its pre-genocide number, but also the compounding impact on

birthrates and retention of members by rape and other torture; rampant

poverty; long-term effects of malnutrition; global dispersion; loss of

religious, educational, and other institutions necessary for the

cohesion of Armenian communities; and much more. To these harms are

added the extensive lost property of Armenians. Not only were virtually

all land, businesses, farms, warehouse inventories, food stocks, and

other such property taken from Armenians, but the mass expropriation

reached down to the most trivial items, from kitchen pots and pans to

the clothes on deportees’ backs and shoes on their feet. Turkish

activist and writer Temel Demirer has stated of this mass theft that it

was with this Armenian property that the national economy of the new

1923 Turkish Republic was founded.

5 What is more, since this

time, Armenians have lost all that would have been built on this wealth,

which compounds daily, with many living out their lives over the past

century impoverished because what was theirs was denied. And this mass

of material resources has not just disappeared: Wealthy Turkish

families, the government, and average people have received the

cumulative benefits of all that this wealth has allowed them to build,

its daily compounding interest. In fact, scholars such as Uğur Ümit

Üngör and Mehmet Polatel have traced expropriated Armenian property

right through to contemporary national and regional elite families, some

of whose family fortunes were built with the property pilfered from

exterminated Armenians.

6

The destruction of religious, educational, cultural and artistic, and

other aspects of Armenian communal existence, coupled with demographic

collapse and global dispersion, have rendered Armenian identity and

peoplehood fragile, requiring continual, draining efforts by members of

the community just to prevent their erasure. The demographic destruction

and individual as well as state territorial expropriations of the

1915-23 period are the most important factor in the verity that today’s

Armenian Republic is a small, landlocked country of barely 3 million

facing a gigantic, economically and militarily powerful Turkey of 70

million—a hostile Turkey that enjoys tremendous regional power and

geopolitical prominence that allows it nearly free reign in its

treatment of the Armenian Republic. Even had the genocide occurred but

Ataturk’s ultra-nationalist forces not invaded and conquered the bulk of

the 1918 Armenian Republic, historian Richard Hovannisian has estimated

that the Armenian Republic today would be a much larger and secure

state with a population on the order of 20 million.

7 What

would it mean for such an Armenia to face a territorially and

demographically smaller Turkey today? Surely Armenians in the republic

and around the world would be infinitely more secure and enjoy a level

of community well-being that became a fantasy on April 24, 1915.

Armenians in Turkey have borne a great share of the genocide’s

impact. After almost a century of suffering in relative silence, the

legacy of oppression and violence is now well known. Reflecting on

Native Americans in the United States, Mayans in Guatemala, survivors of

childhood sexual abuse, and other such groups, it seems clear that the

most difficult situation a victim group or individual can find itself,

himself, or herself in—even beyond the terrible situation of all

victims—is to remain subject to the perpetrator group or individual. Far

beyond the painful, demeaning effects of denial for a group that has

escaped, the situation of those still under perpetrator hegemony is to

be constantly forced to live within the world of violence and power of

the original harm, feeling always on the edge of being pushed back into

the violence, with no escape from the terror, nor space simply to mourn

what happened. And perpetrator groups and individuals seem never content

even with that level of continuing harm to their victims but, as we

have seen with Turkey, continue with such things as repression of

non-Muslim minority foundations and expropriation of their property

8 and the assassination of Hrant Dink.

Reparations for the Armenian Genocide are certainly legally,

historically, and morally justified in abstract terms. But, as the

Armenian Republic struggles economically and politically, the Armenian

Diaspora expends greater and greater energy to be less and less

effective in preserving Armenian identity, and Armenians in Turkey

continue to live under threat and oppression, reparations are an

absolute need if the Armenian Republic, the Armenian Diaspora, and the

Turkish-Armenian community have any future at all, and the 1915 genocide

is not to succeed by 2065. The current trends make it a real

possibility that the state will fail in the next half century, the

Armenian-Turkish community will become a perpetually subjugated group

with no hope of true participation as full citizens in their state and

its society, and Armenian identity will become a residual and decaying

aftereffect of genocide, rather than the vibrant, living community

anchor it should be.

The full history of the Armenian Genocide is far from written.

Coupled with this analysis of the need for reparations, it is useful

to consider some of the standard objections raised against reparations

in a case such as the Armenian Genocide. First, another false truism is

that time heals all wounds. Nothing could be more wrong, unless by

healing we mean that perpetrator groups and the world in general

eventually can forget about a past genocide when the victim group

finally fades away in the ultimate triumph of genocide. Unless the harms

of a genocide are addressed, then they persist and in fact compound

over time, with each generation of the victim group grappling with them.

[A]nother false truism is that time heals all wounds.

Nothing could be more wrong, unless by healing we mean that perpetrator

groups and the world in general eventually can forget about a past

genocide when the victim group finally fades away in the ultimate

triumph of genocide. Unless the harms of a genocide are addressed, then

they persist and in fact compound over time, with each generation of the

victim group grappling with them.

If time is running out, it is running out for the perpetrator groups.

As Armenians, Assyrians, and Greeks join what I will call the “100-plus

Club” of groups whose experience of destruction has endured for more

than a century, it is Turkey that should regard the sands flowing down

in the hourglass with foreboding and disquiet. As time passes, harms

become more difficult to repair, and those in the victim communities who

have lived and died without justice can never receive it. Already Japan

is on the verge of failing utterly to repair in any way at all the

harms done to the Comfort Women—actually, many if not most were underage

girls—whom its military government subjected to brutal sexual

enslavement in the 1931-45 period. These girls and women were interned

in hellish stations and raped sometimes 30 times a day, 6 days a week,

for months and even years. Many died, but those who survived have for a

quarter century demanded an apology and meaningful atonement through

material reparations (necessary for such things as their medical bills

as they deal with the life-long effects of their horrific captivity,

often without children helping them because of the hysterectomies forced

on them). Japan has refused and denied, and now many former Comfort

Women have passed on. Japan has already lost the opportunity with them,

and as a state and society must bear the taint of this terrible human

rights abuse as long as it continues to exist. And once the last former

Comfort Woman is gone, the taint will be complete. I have termed this

kind of impact an “impossible harm.”

9

Turkey and other such perpetrators have the benefit that national,

ethnic, racial, and religious groups, if they survive attempted

annihilation, have identity cohesion over time, and so as long as

genocide does not succeed completely, there is always a group that can

receive efforts at repair. Of course, Turkey has already irrevocably

lost its greatest opportunity to repair the harm to survivors and

itself, as there are virtually no direct survivors of the genocide alive

today. There is no longer anything to be done about this intentionally

lost chance. But much can still be done. Unfortunately, with each

passing day the harm grows and there are more and more members of the

victim group who have lived and died without repair and who thus

represent a growing permanent taint for the perpetrator state and

society. Not only have Turkey and states and societies like it so far

failed to do right by Armenians, Assyrians, and Greeks, and other victim

groups, respectively, but they are failing their own future generations

by imposing on them the stigma of a more and more irreparable genocide.

Second, even setting aside the legal status of Turkey as the Ottoman

Empire’s continuing state and Turkish Republican forces’ perpetration of

the second phase of the Armenian Genocide from 1919 to 1923, Turks in

the Turkish Republic today do bear responsibility for addressing the

harms of the genocide. They are not in any way to blame for it,

10

even when they deny it (though they are separately culpable for

denial). But, as their state and society continue to hold the gains made

and to benefit from them, and Armenians continue to suffer from the

material, political, and identity losses sustained, today’s Turks have

an obligation to repair the damage as much as possible. Of course,

nothing approaching full repair is possible: They cannot bring back the

dead, nor can they turn back the denial clock to erase all the damage

done as the harms to Armenians who have lived and died have compounded

for a century. But, as the AGRSG Report lays out, significant symbolic

and material reparations are very possible today; they require only the

political and ethical will to make them. Making them is not unfair to

present-day Turks. This is not a burden forced on them by Armenians, who

should just go away quietly. On the contrary, the burden of genocide

has been forced on present-day Turks and Armenians by the perpetrators

of the genocide, who damned their progeny to the moral taint of genocide

for this past century and beyond. However extensive a reparations

package is made by Turks today, the burden they assume in giving

reparations is the barest tiny fraction of the burden of loss and

suffering the genocide still imposes on Armenians. The push for

reparations is asking Turks today to shoulder just a small part of the

burden borne by Armenians, to share just a part of the unfairness

history has imposed. If this is a sacrifice for Turks today, this is

appropriate: Such a sacrifice confirms the true rehabilitation of the

Turkish state and society, which were formed in part by the many

genocide perpetrators in the Turkish Republic’s government and military,

and which have retained deep within their political culture the same

genocidal attitudes toward past victims as drove genocide in the first

place. Reparations are necessary for the rehabilitation of the Turkish

state and society, as surely the Kurds and those residual Armenian and

other communities in Turkey could attest.

[A]s the AGRSG Report lays out, significant symbolic and

material reparations are very possible today; they require only the

political and ethical will to make them. Making them is not unfair to

present-day Turks. This is not a burden forced on them by Armenians, who

should just go away quietly. On the contrary, the burden of genocide

has been forced on present-day Turks and Armenians by the perpetrators

of the genocide, who damned their progeny to the moral taint of genocide

for this past century and beyond.

Even a substantial territorial return to the Armenian Republic, which

seems to cause an existential crisis for some Turks, is not an absurdly

irrational imposition. How dare, many Turks say or think, Armenians

demand

Turkish land? But that very thought betrays the problem.

This land became Turkish through the genocidal ideology that

depopulated it of Armenians. Holding that land against what is right

means holding on to that genocidal ideology. That is why land

reparations are crucial for Turkey’s rehabilitation away from genocide.

Another objection is that the quest for reparations, particularly

territorial, is a hopeless pipedream kept alive by deluded so-called

“Armenian nationalists” who refuse to live in reality. Realpolitik is

the dominant ethic of international relations, and it leaves no room for

moral imperatives toward repair. Armenians are too weak to compel

reparations, and should focus on what is actually possible. What is

more, international law, however much based on the principle that harms

should be repaired, simply does not have the legal and procedural

mechanisms to deal with the Armenian and other long-standing cases. As

the perpetrator groups have held out for so long, they have in fact made

law irrelevant. And even where laws and procedures are available,

domestic courts usually want no part of such overarching concerns, and

international courts are subject to a range of political forces that

bring the matter back to realpolitik again. Wherever victim groups such

as Armenians turn, the situation seems hopeless.

How dare, many Turks say or think, Armenians demand Turkish

land? But that very thought betrays the problem. This land became

Turkish through the genocidal ideology that depopulated it of Armenians.

Holding that land against what is right means holding on to that

genocidal ideology. That is why land reparations are crucial for

Turkey’s rehabilitation away from genocide.

This is just what those who know that their power rests on genocide

and oppression want them to think. Again and again victim groups,

oppressed groups, are told that there is no hope, that they have no

power, that realpolitik trumps morality every time. Why do the powerful

say this? Because they know that to hold their power and ill-gotten

gains, they must convince their victims to believe it. For, once victim

groups believe that nothing can change, nothing will change. We must be

thankful that slaves and abolitionists in the United States and around

the Western world did not believe that the system of slavery of Africans

was inevitable and would not fall. Surely countless slave holders in

the U.S. South made this claim in 1855, only to see the end of slavery

within the decade. And their descendants said the same thing about

segregation, but Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, and millions of

others refused to believe it and continued pressing, until the world did

change. Surely Gandhi was told in 1935 that decolonization was a

useless pipe dream, and thankfully he refused to bow to such an

oppressive “reality.” Nothing in the world is given, and as much as

human history is filled with genocide and oppression, it is filled with

the efforts of those who oppose and overcome it. However much we might

debate the nature of “justice” as a philosophical context, divergent

ethical theories all seem to agree that causing others to suffer is

wrong and imposes an obligation to help those caused to suffer. Rather

than succumbing to the apparent limits of politics and law, if they do

not allow justice (though from ancient times promotion of justice has

been their sole validation), then we must transform politics and rewrite

the law. Politics and law must conform to genuine justice, not dictate

to humanity some stunted, anemic shadow of the just.

The examples of King, Gandhi, and others suggest something else we

should consider. I have written before about the importance of group

reparations for such peoples as Armenians, over individual reparations,

which do not contribute to the rebuilding and reconstitution of the

people as a whole.

11 But now I would like to push these ideas

further. The current reality we live in across the globe is a world

order formed through the forces of aggressive war, colonialism, slavery,

apartheid, economic exploitation, mass rape and sexism, and, of course,

genocide.

It might be said that, because the deep-reaching forces of

destructive change have been so dramatic and blatant, and their result

so often absences that mean there is nothing to see, the denial process

inherent in human political arrangements and societies has led us all

the more readily to miss the impact of the past on the present. Benedict

Anderson might have highlighted the process by which what became

nations in Europe and elsewhere were built through a linguistic and

conceptual homogenizing process,

12 but as Ernst Renan

explained a century before him, this process of nation formation is

accomplished through a long period of destruction that can include both

the physical elimination of divergent populations and the cultural

destruction of competing language, ethnic, and other groups.

13 Let us not forget that the Christianization of Armenians in the 4

th

Century of the Common Era was accomplished through the rampant and now

quite regrettable destruction of the religion, culture, and art of the

paganism that existed before. To recognize the forces of destructive

change that have made the reality we inhabit is not very hard once we

know that we are looking for incongruous presences and bright, shining

absences. Consider Europe, for instance, with its multitude of cultures;

languages; political arrangements; great philosophical, literary, and

artistic traditions; and cuisines. Yet, in the midst of our gaze, a

nagging twinge at the edge of consciousness and history becomes a full

question: Where are the Jews? To answer in Israel or the United States,

Canada, or elsewhere begs the question. A conglomerate of groups sharing

a religion and sense of identity in areas from Russia to France, this

group was a central part of the very fabric of European identity and

society for a millennium, but now they are largely gone relative to that

prior presence, their great contributions erased through centuries-ago

expulsions from England, forced conversions in Spain, pogroms in Russia,

and more, and then, of course, the maximal moment of anti-Semitic

destruction continent-wide, the Holocaust. The world we have today is

the product of this treatment of the Jews.

The absence of European Jewry is inverted in the presence of African

Americans in the United States. They are there every day, in the highest

echelons of celebrityhood, politics, and business, but also in the

great ghettoes that punctuate major and minor U.S. cities, in the U.S.

prison system that incarcerates more people than the rest of world

combined, and in the anxieties of polite white society. How many

thousands of hours of political talk shows and academic and government

reports try to sort out why the majority of African Americans are in a

place of rampant poverty and violence. Why is such a high percentage of

Blacks poor? The answer seems so complex that it is unanswerable. But is

it? Perhaps I betray the simple limits of my mind by pointing out what

seems obvious, but is not Black poverty the direct result of slavery and

Jim Crow segregation and discrimination, or more exactly the fact that

the extreme damage done by both has never been repaired? The release of

slaves followed generations of legally and violently imposed illiteracy

and educational exclusion; of family destruction, torture, rape, and

degradation that materially undermined and psychologically traumatized

the population; and the loss of 250 years of extorted free labor to

build the Colonies and then the United States. While for a brief moment

during reconstruction some small repair was made, in the form of the

land necessary for former slaves to become working-class citizens, the

40 acres and mule were quickly repossessed by Uncle Sam and the slave

owners then compensated for the loss of

their property—their

property.

The vast majority of African Americans were plugged into the already

genuinely inhospitable capitalist economy of the United States without

capital, training or education, or full recognition as human beings. Is

it any wonder they started poor? That they stayed poor? Despite some

upward (and downward) mobility in the United States, class is generally

constant across generations, for the simple reason of inheritance. Those

with money give it to their offspring, who are plugged into the economy

with property, while those without it have nothing to offer their

children, who end up at the same low level as their parents, and

grandparents, and great-grandparents. Add to this the powerful

exclusions and discriminations of Jim Crow, which kept Blacks from

joining the various Caucasian immigrant groups in their upward economic

climb and took away whatever they were able to get, to keep them right

where they always had been, and Black poverty today is not just

explicable, but inevitable.

While setting right each instance of such a historical wrong is a

step in the right direction, this approach to reparations is not simply

an aggregation of cases by single groups. Reparations is the process of

global transformation through which we can finally begin to rework our

world away from the structures resulting from genocide and all these

other destructive, terrible forces, toward a vision in which all human

beings have dignity and enough to eat, in which all people can live free

from violence and degradation. “Solidarity” in its true sense is not

just recognizing the similarity of experiences and struggles and lining

up different groups together in a mutual support network. It is built on

recognition that victim groups are together in a single, unified,

shared world formed by genocide, slavery, imperialism, and so on, and

that, at the deepest level, they face a common force of oppression and

destruction that must be addressed as a whole if the local success of

one group will not be cynically balanced by a shift in the structure

that will mean victimization of other groups. The problem is so big and

individual groups’ parts so interwoven that it can only be solved for

each group through a coordinated global approach. As each specific group

pursues justice against the legacy of mass violence and oppression it

has experienced, it must do so in a way that resonates with and promotes

every other group in the struggle for justice across the world.

Explained this way, the task ahead surely appears daunting. If the

world has taken more than half a millennium to become what it is today,

it is a given that such a broad transformation will not happen overnight

through some fantasy of revolution. Fortunately, in the past decade,

there has emerged a global reparations movement. Jews, Hereros, African

Americans, indigenous North and South Americans, Aborigines, South

African Blacks, former Comfort Women, Assyrians, Greeks, a host of other

groups, and, yes, Armenians are more and more recognizing their common

cause and working toward the great goal of a repaired world. However

long it will take, if we are committed to a truly just and good world

order, we must all actively participate this struggle.

Notes

[1] This concept and approach are first introduced in Henry C.

Theriault, “Denial of Ongoing Atrocities as a Rationale for Not

Attempting to Prevent or Intervene,” in Samuel Totten (ed.),

Impediments to the Prevention and Intervention of Genocide: A Critical Bibliographic Review.

“Genocide: A Critical Bibliographic Review” book series, Vol. 9 (New

Brunswick, NJ, USA: Transaction Publishers, 2013). pp. 47-75.

2 Jermaine O. McCalpin, “Reparations and the Politics of Avoidance in America,”

The Armenian Review 53:1-4 (2012): 11-32.

3 This line of argument is developed in Henry C. Theriault, “From

Unfair to Shared Burden: The Armenian Genocide’s Outstanding Damage and

the Complexities of Repair,”

The Armenian Review 53:1-4 (2012): 121-166.

4 The full report is available at www.armeniangenocidereparations.info.

5 Temel Demirer, presentation, “The ‘Armenian Issue’: What Is and How

It Is to Be Done?” panel, “1915 within Its Pre- and Post-historical

Periods: Denial and Confrontation” symposium, Ankara, Turkey, April 25,

2010.

6 Uğur Ümit Üngör and Mehmet Polatel,

Confiscation and Destruction: The Young Turk Seizure of Armenian Property (London, UK: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2011).

7 Richard G. Hovannisian, public lecture, Armenian Relief Society Armenian Summer Studies Program,

Amherst College, July 1991.

8 Sait Ҫetinoğlu, “Foundations of Non-Muslim Communities: The Last Object of Confiscation,”

International Criminal Law Review 14:2 (2014): 396-406.

9 Henry C. Theriault, “Repairing the Irreparable: ‘Impossible’ Harms

and the Complexities of ‘Justice,’” in José Luis Lanata (ed.),

Prácticas Genocidas y Violencia Estatal: en Perspectiva Transdiscipinar (San Carlos de Bariloche, Argentina: IIDyPCa-CONICET-UNRN, 2014), pp. 182-215.

[1]

0 This distinction is informed by George Sher’s

treatment of the difference between “blame” and “responsibility” in

“Blame for Traits,” plenary address, 28th Conference on Value Inquiry,

Lamar University, Beaumont, TX, USA, April 14, 2000.

[1]

1 Henry C. Theriault, “Reparations for Genocide: Group Harm and the Limits of Liberal Individualism,”

International Criminal Law Review 14:2 (2014): 441-469.

[1]

2 Benedict Anderson,

Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, rev. ed. (London, UK: Verso-New Left Books, 1991).

[1]

3 Ernest Renan, “What Is a Nation?”, Martin Thom (trans.), in Homi K. Bhabha (ed.),

Nation and Narration (New York, NY, USA: Routledge, 1990), pp. 8-22.