Special for the Armenian Weekly

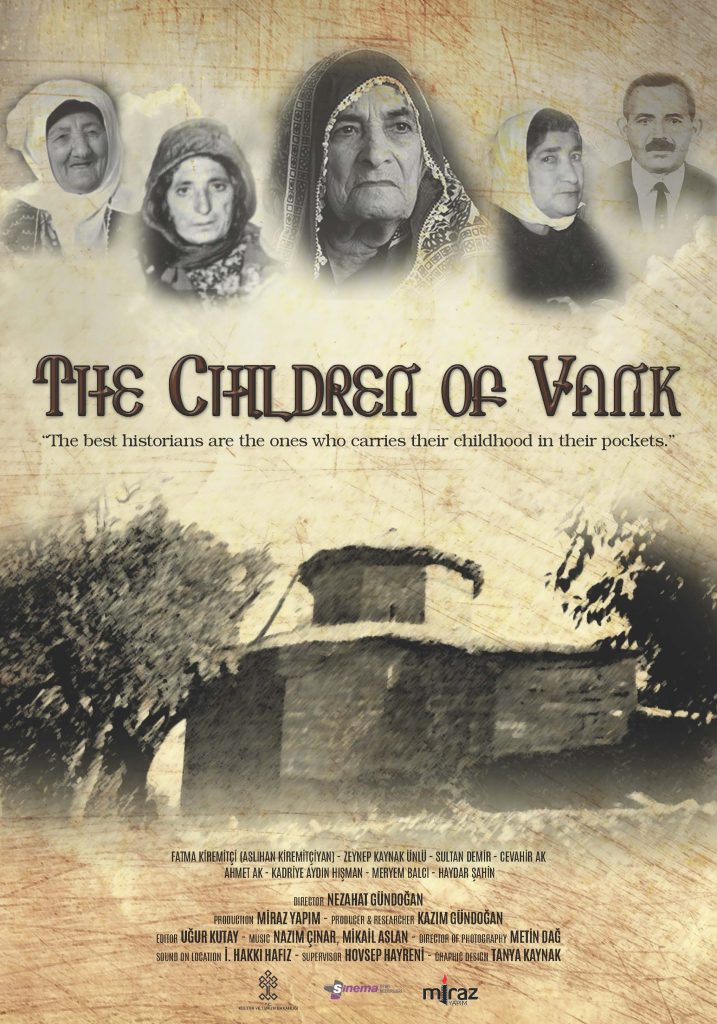

A new Turkish documentary about Islamized survivors of the Armenian Genocide premiered in Istanbul on Feb. 9.

The documentary The Children of Vank tells the story of what happened to the few survivors of the 1915 genocide in the province of Dersim (“Tunceli” in Turkish) and of the 1937-38 Dersim massacre.

According to the documentary, the Armenian survivors of these two genocides were exiled by the Turkish government to other places across Turkey.

Due to the forced Turkification and Islamization policies of the Turkish government, the Armenian names of the survivors were changed and they were given Turkish names. They were then made to convert to Islam by reciting the Shahada, the public recitation of Islamic belief that is declared by all converts to Islam. Some were raised as Alevis in Alevi households.

The film is named after the Surp Garabed Vank (Saint Garabed Monastery) in the village of Halvori in Dersim. The word “Vank” means monastery in Armenian.

The Surp Garabed Vank, which is believed to have been built in the ninth century, was the only Armenian place of worship in Dersim that was not destroyed in the Armenian Genocide.

The monastery was bombed by Turkish forces in 1937 and its priest was arrested. It was completely demolished in the massacre in 1938 and the priest was brutally murdered—alongside other Armenians and Qizilbash/Alevis in the village of Halvori Vank.

“The Turkish state targeted all Qizilbash/Alevis across Dersim as well as the Christian community in that village in the 1937-38 genocide,” said Kazim Gundogan, the producer of the movie, speaking to the Armenian Weekly. “Almost all of them were killed. That is why, we named the people whose stories we told 75 years after the genocide ‘the children of the monastery (Vank)’.”

Kazim Gundogan and Nezahat Gundogan, the researchers of the movie, traced the Armenian survivors of these two genocides in the provinces of Konya, Bolu, Istanbul, Izmir, and Dersim and conducted interviews with them. Kazim Gundogan also wrote a book about the Armenians of Dersim entitled The Children of the Priest: Armenians of Dersim 1. “Our research on Armenians of Dersim is ongoing. We will publish a second book about the stories of the Alevi, Muslim, atheist and Christian Armenians of Dersim at the end of this year,” said Gundogan.

The documentary details the courageous yet traumatic lives of the surviving children and grandchildren of the monastery. It describes their shattered memories, their efforts of searching for their roots and their journey back to Dersim.

Gundogan emphasized that he would like to share the documentary with those who want to learn more about the Armenians of Dersim and the 1938 massacre by organizing premiers and talks about the movie across the world.

Ahmet Ak, who learns about his grandmother’s Armenian identity, says in the documentary: “I think she was so scared that she did not share anything with us. It is so hard to be an Armenian in these lands. And they lived through these difficulties in person so deeply.”

Kazim and Nezahat Gundogan have also produced two ground-breaking documentaries about the 1938 Dersim massacre: Two Locks of Hair: The Missing Girls of Dersim (2010) and Unburied in the Past (2013).

In 2012, the two also published a historic book called The Missing Girls of Dersim, which contains more than a hundred stories as well as several documents detailing the painful experiences of the surviving children of Dersim, who were kidnapped by Turkish soldiers or bureaucrats following the massacre.

At the press conference organized during the premier of the Children of Vank, the director, Nezahat, said that it took them four years to complete the making of the documentary.

“We all know that historical truths are covered up, hidden and denied by the official ideology and the official history narrative in our country. Hence, it takes a very long time to chase the truths and reveal them,” said Nezahat. “It is hard to be a Kurd, an Alevi, a woman, a homosexual, a child—to be the ‘other’— in these lands… But being an Armenian is even more difficult. Armenians are seen as ‘the other of the other,’” Nezahat added.

According to Nezahat, the documentary is not just movie, it is what the filmmaker calls “a struggle for truth.” “I hope this movie will pave the way for revealing many other untold stories,” Nezahat explained. “And I hope it will help stop even greater sufferings and atrocities from taking place again.”