WATERTOWN (A.W.)—In late October, Archbishop Shahan Sarkisian, the prelate of Aleppo, granted an interview to the Armenian Weekly. The Archbishop was in Boston to meet with community organizations and to personally thank the Armenian Relief Society (ARS) for its efforts in providing assistance to the Syrian-Armenian community. During the hour-long interview—conducted in Armenian—Archbishop Sarkisian gave an overview of the Syrian crisis, and spoke about the challenges facing the community today. He was direct in criticizing the worldwide Armenian community for failing to respond to the crisis in a united and comprehensive manner. He said that there is a difference between being concerned and interested—and argued that what he was witnessing was interest and not concern. To be concerned, he added, means to take on responsibility, and that has been missing in the relief efforts.

Archbishop Sarkisian emphasized the importance of keeping Armenian schools in Syria open for students—a cause he considers vital to the survival of the community. “Armenian schools are the light of our eyes,” he said, and they need the support of the diaspora. He also spoke about communal organization, relations with neighboring communities, and the dangers before them.

The archbishop also talked about the media and its failures—calling the leading media outlets “messengers of lies.” He criticized news outlets for regurgitating unverified information, likening the misinformation to cancer. For instance, he said, evidence is lacking in the fate of the destruction of the Armenian Church and Genocide Memorial in Der Zor, and he could not say with certainty who the culprits were. He noted that the destruction of the church did not fit ISIS’s modus operandi, since the group typically banks on publicizing their acts for maximum shock effect and propaganda.

He held, however, that the role of Turkey is “great” in the Syrian crisis, but that revealing evidence would only jeopardize the safety of the community.

Archbishop Sarkisian spoke at length about the importance of preserving the Syrian-Armenian community and the role it could play in the larger Middle Eastern—and in today’s geopolitical—reality. The Armenian community is a bridge, he said, between the West and the East, as Armenians occupy a unique position as a trusted people by both the West and the East. He spoke about the dangers of being such a bridge, and about the community’s policy of maintaining positive neutrality.

The archbishop also criticized what he saw as the “naiveté” of the diaspora when publicizing the various fundraising events and sums raised for Syrian-Armenian relief efforts. He argued that such publicity has in the past jeopardized the safety of the community, especially when kidnappings-for-ransoms were rampant.

Although the archbishop gave a number of interviews while in North America, he explained that he had turned down such opportunities beforehand for fear of repercussions on the community. If my words are taken out of context, he said, it is the community who will suffer the consequences.

The archbishop arrived in the U.S. on Oct. 13, and proceeded to tour Armenian communities in North America, including Canada. He returned to Syria on Nov. 6.

Below is the interview in its entirety.

***

Nanore Barsoumian—Thank you for this opportunity. As

you may know, the Armenian Weekly has been following the Syrian crisis

closely. Armenians worldwide are concerned about the situation in Syria.

Please give us an overview of the crisis—not just in terms of the

Armenian community, but as it applies to the whole of Syria.Archbishop Shahan Sarkisian—A distinction must be made between being concerned and being interested. Most Armenians might be interested, but are most Armenians concerned about Syrian Armenians? Not from my perspective. I don’t see it.

Judging from what I’m seeing, first, it is a disorganized way of being concerned. Second, I see the concern as being more about financial considerations and property. There is a community there and a hundred years after the genocide it is settled and organized. But the Aleppo Armenian community has a nearly 1,000-year history. After the genocide, at the doorstep of the Centennial, Armenians are generally interested in what is happening. That sort of interest does not only apply to Armenians but to anyone on this planet who is interested in what is going on in the Middle East and, specifically, Syria. For me, concern is something else. To be concerned means to be committed, to assume responsibility. And assuming responsibility does not mean to send financial assistance to Armenians in Aleppo and Syria. Not at all. That is only one part of an entire program that does not exist. This is the core issue.

To be concerned means to be committed, to assume responsibility. And assuming responsibility does not mean to send financial assistance to Armenians in Aleppo and Syria. Not at all. That is only one part of an entire program that does not exist. This is the core issue.But to answer your question, the Middle East has always been a stage for wars and upheavals. Recently, there have been many color revolutions, including the [Arab] Spring uprisings, one wave of which took place in Syria, and then turned into armed clashes. The fighting spread. The fire spread from one place to another, just as it would in a forest with dry leaves.

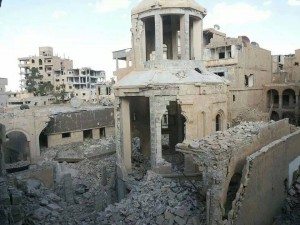

Today, without exception, all the cities and villages in Syria are in a state of war. There are some places that the war has devastated so badly that there is no space left for fighting, and the situation has therefore calmed down—not because of peace deals. There are other places that are still in the process of being ruined and the devastation continues. I am neither an expert in international and local diplomacy, nor in political science. I am not an expert in the military field. But I do know that although Syria is one entity on the map, the country is fragmented into numerous parts.

The Syrian-Armenian community in the Middle East has been in constant communication and continues to have relations with various Armenian, Christian, and local peoples, nations, religions, and cultures. It cannot remain indifferent or passive. In general, from the beginning of these events, our position—a costly and difficult position—was to adopt a positive stance: We would not participate in any military activities. We would not side with anyone. Some people call that positive neutrality, which is a political concept. Ours is a variation of this positive neutrality. People ask, ‘Which side are you on—this or that side?’ We tell them, ‘We are on the third side.’ In terms of an alternative, we represent a third side. But because we are few in numbers, and our voices are hard to hear, we are forced—just like every community, Christian and Muslim, and every ethnic group that makes up the whole of Syria—to deal with the situation that has been created in the country. We are interested in our surroundings, and we help those around us, but we give priority to our community.

Unfortunately, Syria is presently facing uncertainty. There is no sign of peace on the horizon. The war continues and, like everyone else, we too must suffer the fire, the casualties, the kidnappings, the destruction, and the various other types of harm.

The main problem is mis-information—inaccurate information…. the media is supposed to be the messenger of truth, but instead is a messenger of lies.

N.B.—Now there is a new reality, Da’esh (ISIS). How does their treatment of minorities, such as the Yazidis and Armenians, differ from others involved in the conflict? Do you see it as a coincidence that the very same day Armenia celebrated the anniversary of its independence, Da’esh reportedly destroyed the Armenian Church of Der Zor? The destruction also came two days after Catholicos Aram I announced he would sue Turkey over the return of the Sis Catholicosate properties.

S.S.—First, let me be a bit critical, because in today’s world, information can be artificial. The world’s PR machine—whose main outlets are television, social media sites like Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and others, and on a lesser plane the print media—often tries to get its information from safe sources. The big journalistic machine disseminates news, and others repeat that information, sometimes by paraphrasing it, or making some changes. So the main problem is mis-information—inaccurate information.

This resembles someone who has cancer and can’t get rid of it. This is a cancer. This is not my job. I have had nothing to do with the media specifically for this reason—and it is a key reason because the media is supposed to be the messenger of truth, but instead is a messenger of lies. Sometimes it outputs information without even fact checking, or creates an atmosphere of shock. It’s an accepted reality. You don’t see television programs about serious topics, nor do you see it online. Something has to be bizarre for people to become interested; for example, when they show a beheading, people find that interesting because it awakens in them an animalistic instinct, and that interests them. There is no other reason.

N.B.—You mean it shocks people. It’s shocking news.

S.S.—Yes, and they find it interesting. I’m going back to what I was noting earlier about being interested. Only a part of the information that comes from the media is true, but is not verified. For example, who destroyed the Der Zor Holy Martyrs Memorial and Church, and why? There is no verified evidence about it. It’s the analysis that makes you think that on this date this happened, or that on this date this was said, and so that means that these groups were responsible for it. This is one side of it.

The first photos of the destruction of the Armenian Genocide Memorial Church in Der Zor emerged on Sept. 24.

N.B.—But we know that the church has been destroyed.

S.S.—The photograph makes it clear—but who did it, and why? The answer has been subject to the analysis of journalists and politicians. But for us to come out and say these are the people responsible… We know the groups we’ve had conflicts with, and they know us. But those that we have not had issues with, why should I name them [as culprits]? That would only turn their attention to us. Because of that, this group that has invaded large parts of two countries has had no direct conflict, relation, or communication with us. Absolutely none.

In the beginning of the events in Syria, especially the events in Aleppo, we had numerous members of our community kidnapped. More than 100 of them. That was a phase when kidnappings were frequent. Ransoms were paid, and finally that phase faded. The practice faded.

We were able to keep a balance until today. Two principles were essential in keeping that balance: One of them was [respecting] the country’s territorial integrity—that we are Syrians, and we use the term “the Syrian Homeland,” not the term “Our Homeland.” We say, “Syrian Homeland.” If a citizen of the United States of America says that this is an alien homeland [օտար հայրենիք], it means that they have no right to live there. This is especially true in the case of Syria, and in our case. We have been living in Syria for a millennium. There are few communities in Aleppo that are as old as us—you can count them on your fingers. Just to remind you, the Armenian Forty Martyrs Cathedral [Սրբոց Քառասուն Մանկանց Մայր Եկեղեցին] has a history of at least 500-600 years—and that’s just after its renovation. A few hundred years before the renovation, it must have been a little chapel that Armenian pilgrims used on their way to Jerusalem.

Our history in Syria did not begin with the genocide. Wherever Armenians have gone, they have brought good with them. We have contributed to the societies we live in—and that’s because we have felt at home wherever we’ve gone. We haven’t felt like outsiders. That’s why the country and the people are above all else. We neither side with groups nor with different authorities.

Sitting here in the Hairenik offices, I remember [Simon] Vratsian. One of his most famous sayings was: The fatherland is permanent; regimes are not [Հայրենիքը մնայուն է, վարչակարգերը գնայուն են]. That’s why, in Syria, we don’t have issues with anyone.

How are issues created? There are two factors: One is—and this is clear—Turkish involvement.

The second is the naiveté of our nation’s children. Let me give you an example—an example that really pained us at the time. We are grateful to all of our compatriots who have sent us assistance. But is there a need to publicize in every newspaper, on Facebook, and everywhere that we had a fundraising, and raised this much, and sent this much? It’s a common sense issue. It is only lawful and right for someone to receive a receipt, a report, an explanation as to whether the sum they donated arrived where it was intended. But you don’t need to [publicize it]—and it goes against Christianity. When your right hand gives, your left hand does not need to know. And if your left hand gives, your right hand does not need to know.

When the kidnappings began—just so you know—people called us and said, ‘You need to pay us in order for us to release these people.’ Why? Because you have been receiving millions from America. This is not a made-up story. I am a prelate, I am responsible, and I know what I am telling you. This weighs heavy. Those who left the country, that’s their business. But those who are still live there don’t need added hardships on top of what they have already had to endure. It causes pain. And that’s why I will go back to what I first told you: I have not seen a united Armenian effort for Syria and the Syrian Armenians—a pan-Armenian effort. My respects to all the different circles, whatever they may be called—church, state, party, all of them. The Syrian-Armenian crisis is not a local issue. It is one of the biggest crises of the diaspora.

No comments:

Post a Comment