By Christopher Atamian

Peter Balakian, poet, memoirist and scholar, is the author of seven volumes of poetry, four books of prose and several collaborative translations. His 1997 New York Times best-selling book “Black Dog of Fate,” winner of the PEN/Albrand Prize for memoir, is widely credited with setting a young generation of Armenian-Americans on a path toward re-discovering their roots.

Balakian’s “The Burning Tigris: The Armenian Genocide and America’s Response” won the 2005 Raphael Lemkin Prize and was a New York Times Notable Book and a New York Times best seller. His translation (with the late Aris Sevag) of Bishop Grigoris Balakian’s “Armenian Golgotha” has been likened to the Holocaust memoirs of Primo Levi and Elie Wiesel.

Peter Balakian holds a Ph.D. from Brown University in American civilization and has been teaching at Colgate University in the state of New York since 1980, where he is currently Donald M. and Constance H. Rebar professor of humanities in the department of English and director of creative writing. He was the first director of Colgate’s Center for Ethics and World Societies.

Aleppo: Terminus Armenicus and Jesse Jackson, a righteous American

Balakian’s maternal grandmother Nafina Shekerlemedjian Chilinguirian (later Aroosian), who was from a wealthy family in Diyarbakir, escaped almost certain death during the 1915 deportations of Armenians. Nafina’s entire family, except her husband and two small children, had been massacred in the first week of August of 1915. Nafina, along with other surviving Armenians of the region, was put on a forced, hundreds-of-miles-long march through southeast Anatolia’s arid land. The scorching sun burned above them as they were forced marched to the Der-ez-Zor desert in eastern Syria. Nafina’s husband died on the march.

But even those who managed to escape murder, abduction and rape along the way were not guaranteed survival once they arrived.

In Der-ez-Zor, a place like Auschwitz for Armenians, over 400,000 people would perish from starvation, disease or murder.

But it was also in Syria that thanks to the efforts of a committed number of Armenian priests and a few American and European diplomats and missionaries, who ran orphanages in Aleppo, that some Armenians were able to survive. Aleppo had always been an important diasporan center, where Armenians have lived since the ancient times. By the time Nafina made her way to the city at the age of 25, with her daughters Gladys and Alice, Syria’s largest city had been overrun by over 100,000 Armenian refugees, most of them dying of starvation, typhus or malaria.

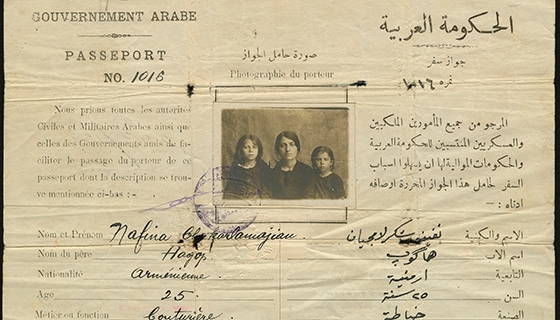

Nafina Shekerlemedjian Chilinguirian with her daughters Gladys and Alice

|

Shortly after arriving in Aleppo Nafina came down with typhus, and lay near death at a local hospital. Her daughters watched, helpless, but Nafina seemed to possess a preternatural will to live. She recovered and continued raising her daughters, working as a seamstress to support them. She enrolled the girls in an Armenian school run by the clergy of the Forty Martyrs Church. “These Armenian priests,” says Balakian, “were heroic in starting orphanages for the surviving children. In some way you could say they were instrumental in helping to save a generation of Armenians.”

Nafina had no family left in the Middle East, and conditions in Syria were worsening. Everywhere she turned she saw only death and destruction: entire families and clans murdered, historical villages erased from the map. Typhus and malaria were claiming the lives of remaining Armenian women and children. But how could her family escape Aleppo?

Nafina heard that Jesse B. Jackson, the U.S. consul, a humane and ethical man, had been helping Armenians. He had cabled the U.S. Ambassador Henry Morgenthau on several occasions in order to keep him abreast of the mass-killings and atrocities. He urged for the United States to intervene and provide relief, financial and otherwise, for the survivors: “I am trying to keep those in the outside towns alive, also, but it is a terrible task, as many persons have been beaten to death, and some hung or shot [by Turkish gendarmes] for having distributed relief funds,” Balakian quotes Jackson in his book, “Black Dog of Fate.”

Directly or indirectly, Jackson was responsible for saving countless Armenian lives. Nafina implored him to help her: he took a liking to the young woman and lent his support.

In a letter dated September 11, 1916, that he penned to Nafina’s brother-in-law Frank Basmajian in Boston, Jackson wrote:

“Sir:

Your sister, Nafina Shekerlemedjian, is in Aleppo, and being in need, has asked me to write you

and request that you send her some money. This may be done best through the American Embassy in Constantinople and this Consulate, by telegraph.

Respectfully yours,

(Signed) J.B. Jackson, Consul”

Thanks to Jackson’s intervention Nafina was able to connect with her deceased husband’s relatives, the Basmajians, in the United States. Soon money arrived from her half-brother Thomas Shekerlemedjian in New Jersey, allowing Nafina to persevere through the dire circumstances of post-Genocide Middle East. Nafina planned her escape to America, despite the fact that in the spring of 1920, passports became hard to come by. In a letter to Thomas, Nafina wrote: “My task in very difficult, until late night I walk around to try and get my passport. Wherever ever you go, they ask you for money. Before it was very easy to get a passport, but now I suffer the utmost difficulties, and until now I don’t know if I will be able to rise and go because after the closing of the borders, there is fear on all sides. Only the road to Beirut is open, and even that is doubtful.”

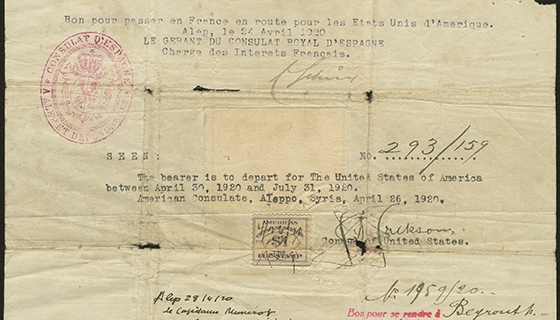

Close-ups of the passport Nafina was able to obtain for herself and her daughters with the help of U.S. Consul Jesse B. Jackson. The back of the document states: “The bearer is to depart for The United States of America between April 30, 1920 and July 31, 1920. American Consulate, Aleppo, Syria, April 26, 1920.” The document bears Jesse B. Jackson’s original signature.

|

Through hard work and an iron will, Nafina made it to America, where she eventually flourished and helped to create one of the Armenian Diaspora’s most celebrated families. “For me, my grandmother’s gift is irredeemable. First, against all odds, she got us here. Furthermore, for me as a writer, what she transmitted has been central to my life; she conveyed to me a complex thread of her post-traumatic mind and experience; she transmitted to me a vision of her survivor experience though folk tales, dreams and encoded symbols; and her unconditional love was a foundation of my life. But without help and some luck, she wouldn’t have made it.

And the humanity of the U.S. Consul Jesse B. Jackson was essential to my grandmother’s survival.

He was her conduit to the West, to America. It shows us that bystanders make a difference; that lives are saved by individuals acting on their ethical instincts,” says Balakian.

Nearly 100 years later, as bombs rain down on Aleppo today and decimate the once-prosperous 150,000-strong Syrian Armenian community as well as the rest of Syria, it’s important to remember that from 1915 to 1923, Aleppo was the stage of another disaster. Thus it is perhaps fitting to remember the brave people who helped a generation of Armenians survive the Genocide and preserve a part of Western Armenia and its 2,500 year-old culture. It was this ethical spirit that helped save Nafina Shekerlemedjian in 1915; it is this spirit that is needed as much as ever today.

The story is verified by the 100 LIVES Research Team.

No comments:

Post a Comment